This is the third post of a series (first post, second post). The first post outlines the central idea—a particular theory of narcissism—of The Last Psychiatrist (“TLP”), a blog from the late 2000s and early 2010s. The second provides some illustrations of his theory as I understand it. This post will give some commentary on and evaluation of TLP’s blogging project. I will post in the coming days an appendix with my notes on the influences informing TLP’s approach, comparisons between his thoughts and other historical and contemporary ideas, and my notes and musings about many of his posts as I initially read them. This series has been a bit of a mess, organizationally, and I have learned the value of prepping series as a whole before letting them loose. Whether I will put this lesson into practice is at this time unknown.

In logic, a valid argument is one where, if the grounds are taken to be true, the conclusions necessarily follow. A sound argument is a valid argument with the additional condition that the grounds are actually true.

It is really easy to make valid arguments. And it is really easy, for readers of certain habits of mind, to get caught up in the validity of arguments and fail to see what they’re missing. I had an English and Philosophy professor in college who said that he often found himself agreeing with whatever philosopher he was reading at the time. While he was reading Wittgenstein, he would think, “yes, yes, of course there is no essence to language”; while he was reading the positivists, he would think, “yes, yes, of course language is fundamentally propositional in nature.” I do not quite go that far—my attempts to flex skeptical muscles is somewhat the subject of a past post—but I have this tendency. When I find a new idea, I like to soak in it, swim around for a while, test for cold spots and undercurrents. I like to get to know it well enough that I fall in love with it at least a little.

What keeps me from sticking to the rivers and lakes I am used to is probably the fact that I am somewhat less congenial than my professor; I retain a contrarian gut. I have never felt less enthusiasm for action to mitigate climate change than while I attended a climate change rally. Every time a self-satisfied smirk in a beanie snaps its beringed fingers in agreement to an absolute banality, my innards roil. Every time a line-up of camo pants nods oh so seriously to affirm a monomania, my eyes (of their own accord) roll and roll and roll. I have been in many a conversation where someone says something I agree with, but too many others do as well, and so I compulsively narrow the idea in an attempt to fish for disagreement: “sure, of course, but—”. None of these reactions are valiant or virtuous, though I believe a few cranks is vital for any resilient community. They are just things I tend to do.

I know others who regard any new idea with suspicion. Any thought has to prove itself worthy of consideration. From the moment it arrives, it is shuttled through various tortures and critiques. And when they agree with something, they take it truly to heart—they seek agreement on the matter, and get pleasure out of others’ assent. At its worst, this leaves them unable to take a new idea on its own merits, or traps them in a poor outlook. Their minds catch on a proposition that seems vaguely out of step with something they [believe that they] know and it holds them from seeing the idea as a whole, on its own terms. At its best, this is just a really good filtering mechanism, and I suspect that they waste far less time than I on ideas not worth considering.1

The compromise I have roughly landed on for now is to retain my sumptuous tolerance for ideas which I find curious, but attempt to restrain myself from their use until I am able to do some compare and contrast. I shop them around to my other ideas and interlocutors, and see how they play together.

Returning to The Hunger Games

Consider the example from TLP on The Hunger Games that I mentioned in the first post in this series:

We can start with the obvious. The book is about 24 kids thrown into an arena to fight to the death, only the toughest, the most resourceful, the strongest will survive, and it better be you because your whole village depends on it. It is such a scary premise that there was some concern it was too violent for kids to watch. Well, big surprise: Katniss wins.

Hmmm, here is a surprise: Katniss never kills anyone. That's weird, what does she do to win? Take as much time as you want on this, it's an open book test. The answer is nothing.

This is not a criticism about the entertainment value of the story, but about its popularity and the pretense that it has a strong female character. I like the story of Cinderella, but I doubt that anyone would consider Cinderella a strong female character, yet Katniss and Cinderella are identical.

The traditional progressive complaint about fairy tales like Cinderella is that they supposedly teach girls to want to be princesses and want to live happily ever after. But is that so bad? The real problem with fairy tales is that the protagonist never actually does anything to become a princess. . . .The Hunger Games has this same feminist problem. Other than the initial volunteering to replace her younger sister, Katniss never makes any decisions of her own, never acts with consequence-- but her life is constructed to appear that she makes important decisions. She has free will, of course, like any five year old with terrible parents, but at every turn is prevented from acting on the world. She is protected by men-- enemies and allies alike; directed by others, blessed with lucky accidents and when things get impossible there are packages from the sky. In philosophical terms, she is continuously robbed of agency. She is deus ex machinaed all the way to the end.

. . .

"But she chooses to commit suicide at the end!" That would have been a choice, but the book robs her of that as well, this is the point. The book does not allow her to make irreversible choices, it lets her believe she is making free choices and then negates them, again, just like a five year old girl with terrible parents.

. . .

She does commit one consciously deliberate act, and it's quite revealing. At the end of the book, she's ambivalent about whether she loves contestant Peeta. But the Games allowed two winners only because they appeared to be in love; so all she has to do, for the cameras, is pretend to be in love with a boy she already likes a lot. But after all she's been through in the arena, this-- what is coincidentally called ACTING-- is what is described, in the shocking last sentence of the chapter, as "the most dangerous part of The Hunger Games."

This is not hyperbole. This is literally correct: for someone who has not ever done it, acting with agency would indeed be dangerous. But those stories aren't fairy tales, those stories are legends. [Emphases in original]

This is, I believe, a valid argument. To the extent that these assertions about The Hunger Games are true, it does rob Katniss of agency, treating her more like a fairy tale princess shuttled through a pastiche of heroism than a responsible, agential hero in her own right. And in its validity (and the soundness of its assumptions regarding heroes, agency, and the like), it is revealing about the nature of heroism, feminism, and fairy tales. But is it revealing about The Hunger Games? I.e., is it sound?

When I attempted to reconstruct this argument for a friend, she made the point that Katniss does act in The Hunger Games. She may not act in the way that TLP wants, but she acts to build relationships and trust. She helps Rue, for instance, which forms a relationship between them that is central to Katniss’s survival. Also, her sacrifice for her sister should not be so easily swept to the side. My friend’s criticism of TLP is that he seems to have a violent, perhaps even chauvinistic or misogynistic, idea of what constitutes action that consequently downplays relationship-building and aid.

TLP has his response. His point: for Katniss, her actions are about impressing people or making people like her enough that they save her, not her saving others. Yes, they are relational actions, but not ones that help those around her (barring Rue and her sister, again). Katniss is playing to B-team hero standards because that is all we are able to expect from women—the problem being with our imagination, not our biology. “Katniss is allowed to exist precisely because she isn't a threat to men but women can think she is.”

I’m not exactly sure how to take this. Much of the drama of the third book concerns how her status as a symbol has, Muad’Dib-style, stripped her of agency. Yes, she saves people by being a symbol, but is coalition-building not action? Isn’t coordination a skill? On the other hand, this is the very point: she is becoming a hero by becoming a thing. Not by being a subject (by acting through her skill and power to save others directly) but by being an object (some thing for others to look at or believe in or organize themselves around). The skill we are being taught is to manipulate and be manipulated. On the other other hand, this critique is diagetic to the series: Katniss was agentic and active as a huntress in District 12, helping provide for her family and supporting others in her community, but the whole story of The Hunger Games trilogy is about the brutal narcissism of The Capitol and its toll on this forthright and honorable hillperson. Some of her agency peeks through, but the story of the series is her losing more and more of it as she is forced to play by Capitol rules, even in revolution. The end Mockingjay, when Katniss kills [omitted], reflects her despair that the true evil of The Capitol—spectacle, manipulation, symbolism—lives on. The Hunger Games contains TLP’s critique of it.

Yet I can see TLP’s response already: that is the reading you found with my help, but it is not the reading that was natural to you, and not the reading that you saw in The Atlantic or on the screen. I noted this quote in the previous post, but this is how TLP sees his interpretations of fiction:

I'm going to offer an interpretation. It won't matter whether this interpretation is correct— none of this actually happened, after all. The point is to ask why no one else thought of this interpretation that, once you read it, will seem to you an obvious one.

So, for TLP, the more important question is: why did you/everyone else assume Katniss was a feminist badass icon and not a feminist tragic heroine? The real question is whether that is entirely true.

All of which is to say that to see an argument fully you have to bring in other arguments and facts. So far, I have considered TLP’s ideas and project contained within the world that it “wants to be true,” as TLP himself might put it. Let’s start adding something new.

I will begin by evaluating TLP’s theory of a narcissistic society—the historical and cultural analysis in which his theory of narcissism is situated. Then I will evaluate his theory on the individual level, and to what extent I think he gets it right. Third, I will evaluate his theory of the cure—how to solve this issue. Finally, I will give an overall conclusion, giving my general thoughts about his theory and discussing the ways I think it is a useful conceptual tool. I expect my next off-schedule post to be an appendix to this one, giving a quick genealogy of TLP’s theory of narcissism and providing links to various TLP posts with my initial, lightly-edited thoughts on them as I made my way through his blog for the first time.

On the Theory of Society

If someone were to go about uttering

Windy, baseless falsehoods:

“I’ll preach to you in favor of wine and liquor”—

That would be a preacher [acceptable] to this people.— Micah, 2:11

Civilization’s New Discontents

Before TLP’s theory of a narcissistic society (drawing heavily on Lasch’s The Culture of Narcissism), Freud gave a very different diagnosis of the psychological tensions at the root of his dominant culture in Civilization and Its Discontents. Freud’s thesis was that an overpowering superego commanded to “love thy neighbor” was struggling to expand its circle of erotic attraction ever-outwards, as the cooperative demands of civilization put more and more burden on its disciplining of the id. Erotic attraction is one of assimilation—make the other part of yourself. Nationalism and the creation of large political communities which must cooperate with one another put more and more pressure on our ability to bring ourselves into line with one another.2 As that pressure increased, shared disapproval of outgroups—other countries, religions, communities, classes, and races—provided an important binding agent. Freud was writing in 1929.

One reason for the Freudian-Marxist synthesis in the postwar era was the belief that Freud’s psychological-identity theory explained the appeal and political power of fascism where Marx’s materialist-economic theory struggled. For Freud, the fruits of civilization are many, especially in terms of material welfare. But these fruits come from large-scale coordination. The psychosocial manner in which (European) countries attempted to square their natural scale with the fruits of modernity was, in the prewar period, nationalism and conformity.

Two notes: (1) this is a very different diagnosis than the ego-addled narcissists of TLP and Lasch and (2) this diagnosis does not feel very apt for our contemporary times.

I think there’s a general sense that something changed after the second world war, perhaps blooming in the 1960s and 1970s when this new “booming” generation came of age. I don’t want to get too deep into what this looked like, but here is one way of seeing the particulars, through the lens of one President Richard Milhous Nixon: 1, 2, 3, and 4.3 For our schematic purposes, though, these young rebels upended Freud’s psychological bargain and brought us into the age of narcissism (not for nothing, TLP likes to call the Baby Boomers “The Dumbest Generation of Narcissists In The History of The World”).

All of TLP’s critiques of our contemporary narcissists should be understood in this context: narcissism was a reaction to the terrible destruction wrought by the dictatorial superego. As I have laid out before, I don’t think things changed in the 1960s and 1970s for no reason. There were very good reasons for people to get crazy and change things. And why narcissism? A lot of it must have to do with television: the success of Martin Luther King Jr. and Gandhi and the Freedom Rides (and especially the particular manner of their success) had as much to do with the open airwaves as it did their moral rectitude and organizational aptitude. Gandhi in the USSR would be an unmarked grave, and “I Have a Dream” just doesn’t mean what it does to us without the television and the photograph. Nonetheless, as I have also said before, a pathology is just a habit left out in the sun too long.4

Narcissism, then, is a political tool as much as it is a psychological one. It is a new psychoeconomic bargain—rather than the pressure of erotic assimilation and conformity, you can allow the superego to atrophy by outsourcing communal standards to an external authorizing agent (the government, the media, etc.) and adopt a liberality towards others. Narrow your interests and your interest in others. Narcissism is also a new political strategy: get the riots and lynchings to stop through eyes, get more eyes everywhere and upon everyone. Shame the senescent authority into taking a side.5

Consider as well that countries outside the US (yes, they do exist!) had countercultural student movements in the 1960s and 1970s. In Germany, students railed against their parents for their complicity in WWII and the lack of discussion of the war’s horrors. While Germany’s memorialization of its role in the war now is admirable, immediately after the war most Germans thought that Nazism was a pretty decent idea that was just “badly applied” and a third regarded Nuremberg as “unfair.” In 1952, 25% of Germans replied to a survey stating that they have a good opinion of Hitler. Denazification was a halting, externally-enforced process until the narcissistic boomers began to protest their shameful parents. In France, the Spirit of ‘68 imported a not-dissimilar rebellious spirit into what had been in large part Charles de Gaulle’s France.

An issue throughout the history of civilization is the tension of increasing epistemic awareness (and therefore regions of concern) without a concomitant ability to affect change at such a scale: we can see things everywhere, so we feel like we can’t change anything anywhere. With the internet pulling us further and further into the rest of the world, the tension only grows. Different psychological strategies are required for dealing with this trouble. The problem with this one—narcissism—is that it has may have left many of us empty to the brim.

Thinking about Capital-H History

TLP is not particularly optimistic about how narcissism is going to turn out for us, especially in the US. His theory is that you can trace a line from fascism, to communism, to narcissism as the great destructive political pathologies of their times. I think that is somewhat compelling, especially as the US and China seem to creep towards more and more open competition.

TLP thinks that America is the narcissistic country. This may be correct, but we were also a pretty communist country during WWI and WWII, and a pretty fascist country (general Wikipedia link) during the same period. It may be that we have always been an incipiently narcissistic country and now we have finally had the chance to be the dominant culture. I’m not sure.

Probably, if you’re going to make this comparison work, you have to put communism and fascism under the academically controversial bucket of totalitarianism and then have narcissism be a reaction against totalitarianism. The conceit of totalitarianism—total control of the private by the public—seems to relate to Freud’s diagnosis of his culture in Civilization and Its Discontents and also seems to mesh well with what the narcissists saw themselves as rebelling against (not for nothing, the Boomers in America commonly accused their staid elders of being totalitarian). So, under his schema, totalitarianism was a European invention exported elsewhere, but not to the same degree as it was practiced at home, while narcissism is an American invention exported similarly. Perhaps. But I wonder.

Considering the big-picture aspects of cultural narcissism, I tend to think of China more. Identifying with/deference to power, obsession with social status, chasing after proxies, central direction of social mores, concern for image and ‘being in a movie’: if we’re doing cultural/political stereotyping, this seems more CCP than USA. Perhaps this is my mild patriotism coming to the fore, but no society seems defined by a more centralized bureaucratic decision-maker than China. I know that America has a lot of status-chasing, but we have yet to pay people to cry at our funerals, from what I gather. We have trackers on our phones, but also VPNs, and every time someone tries to pass a bill giving everyone a general government ID, we start shitting bricks; China is famous for its censorship and surveillance. Lest you think they have us beat on social alienation, I wouldn’t be so sure of that either. See the footnote here for rough comparisons of our two countries’ cultures.

Now, I am really no sinophobe. I will be the first to say that this is one of my least assured conclusions in this post, and it is not really so much a take on Chinese people as it is one on the Chinese government, the country’s stratospheric and dislocating launch into modernity, and the conditions present in the country. And I am really unsure of this take! It is really a birds-eye, ideological view to a knotty, complicated, specific situation. China, in many ways, looks a lot like the future! Anyways.

Our Mercantile Times

TLP likes to talk about mercantilism. He defines mercantilism as the creation of markets and desires in order to service monetary wealth, and a fundamentally zero-sum theory of wealth: more exporting means more goods for you but more money for me, and more money means that I’m richer. TLP thinks the problem with this is that it creates useless desires and leads to various bad economic, political, and geopolitical outcomes. Some of this has proved prescient: he predicted an increase in protectionism in 2008.

First, even if I were to adopt this frame of mercantilism, I would describe it slightly differently. TLP frames mercantilism as creating new markets to serve the goods you have. I would say that mercantilism serves the same, perpetual market for status by creating new ways to market yourself as high-status (cf. status by distinction).

Second, I don’t think that this is the primary mistake of mercantilism, how it is generally contrasted with capitalism, or even how it best analogizes to current political pathologies. The primary mistake of mercantilism was its identification of wealth with currency rather than objects of desire and productive capacity: a fetish of the dollar over the actual goods. This seems, ahem, relevant. There were some clear historical reasons for mercantilism: primarily, that mercenary armies were very important in European warfare at the time. Nonetheless, when your enemy can make more armor, swords, guns, horses, and so on, silver won’t stop them. Now, I should note that in times of geopolitical competition, productive capacity (though still, not monetary wealth) becomes important on a nation state or alliance level. Smart, calculated protectionism is one way to push that interest forward. I am not sure whether we will find such a protectionism in the next, oh, I don’t know, three years and nine months? But it is something to consider.

Turn, Turn, Turn

I don’t want to get too far afield into politics, because I think it is somewhat distracting on the issue of narcissism, even if it can be elucidating at times. Often, people stop thinking when they start talking about politics (present authorship included), and political differences can become a reason to discount even nonpolitical arguments. I will say that I still, hopeful sap that I am, believe in America’s ability to “repair her faults.” In fact, I think TLP is one symptom of that. But I could very easily be wrong.

I believe I have brought up The Fourth Turning before on this blog, but take or leave that particular theory, people seem to believe that winds are changing (though this may be a perennial fact). TLP himself noted that culture tends to change biologically, with the turnover of generations, rather than individually, with people changing their minds.6 On that timescale, we’re nearing a new world: the people with the megaphones in the 1960s and 1970s are retiring (in both senses of the word). No country more than America wants more desperately to not be like its parents, and once narcissism is uncool (read: old), its cultural cachet is so over.

It is not only generationally that things are changing, but economically and informationally as well.

The hot economic sectors are either focused on making actual things in the world (green energy, robotics, semiconductors) or are democratizing white-collar expertise (AI). This is the opposite of the ‘narcissistic age,’ which was most defined by making up ideas (finance, research, software, apps) and creating white-collar superstars (computer programming, television broadcasting).7

Malthusian economics gets a bad rap, but the real irony of it was that Thomas Malthus was pretty much correct on the long-run dynamics of per capita income until when he wrote about it. He published An Essay on the Principle of Population, arguing that any improvement in economic productivity is negligible in how it affects individual welfare because it is quickly swallowed up by increased population. He did so in 1798. Modern economic growth and population dynamics, which obliterated his assumptions by causing economic growth to occur far faster than population growth, began in the United Kingdom in the early 19th century.

In terms of the structure of information and media, I wonder if TLP’s blog isn’t subject to a similar irony. TLP writes about television that “[t]his tube can make or break presidents, popes, prime ministers.” He writes, Manufacturing Consent-style, about how media frames political debates so as to drain them of their meaning. He writes concerned, sure, about how manipulative TV is, but he also writes concerned about the next generation of TV manipulators: whose hands will the TV be in?

At this point, I feel like the best answer to that question is: who cares? We’re not in a TV world now; we are in a world of influencers, podcasters, memes, blogs, newsletters, and forums. We are in a social media world, and everyone fighting over who gets to say what where is fighting over a dead microphone. Which makes TLP’s concern the wrong one: not what happens when the remote control falls into the wrong hands, but what happens when it falls into the hands of no one. Or everyone. Or impersonal algorithms.

TLP may have been an early voice in the wilderness, but his criticisms (or at least their general character) have not become more marginal. For instance, some days, reading Freddie de Boer can feel like reading a disciple of TLP, though I am sure he is not one. See exhibits 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7. I don’t think the full contours of TLP’s thought is going to magically enter the mainstream, but the sort of dissatisfactions with contemporary politics he voiced will become more widespread. People like to take the line from Succession and talk about “serious people.” In one sense, that is what TLP is getting at: are you more caught up with your own petty position, or do you actually believe that something is good? TLP was an early blogger, and an early messenger—in the long run, perhaps the medium will become the message.

Now, what we are moving towards it is difficult to say, and whether it will be good is just as hard. In America at least, it’s unclear whether we still have enough of the old magic to remake the country yet again. And our hints of the future—the tired play between wokeness and antiwokeness—are not exactly exciting to me. You could try to place the two in the old box: political life as an etiquette being the endgame of narcissistic politics. But I am not sure. My hope is that the fracturing of the cable television spectrum of possible political types will lead to something different and less bisected than our current situation. The logic of social media certainly seems to facilitate a type of narcissism, but perhaps its panopticonic posturing is finally so rank and obviously detrimental that we are finally starting to consider at least its effects on children.8

I don’t think anyone can be sure what our new world will bring. More consolidation or more splintering? If it is a splintering, how will this splintering match up with our institutions? Will it imply localism, issue-based radicalism, long-range discontent? Will it lead to more distrust or stranger bedfellows? If everyone has a different echo chamber, does that make you out of necessity be more comfortable dealing with others, or does it make you yet more paranoid and alone? The US moulded a country out of our states, that country broke in two, and now is splintering. But along what lines? In what ways? How will narcissism interact with the new landscape? Will it be aggravated, transformed, or reversed?

Societal Psychiatry

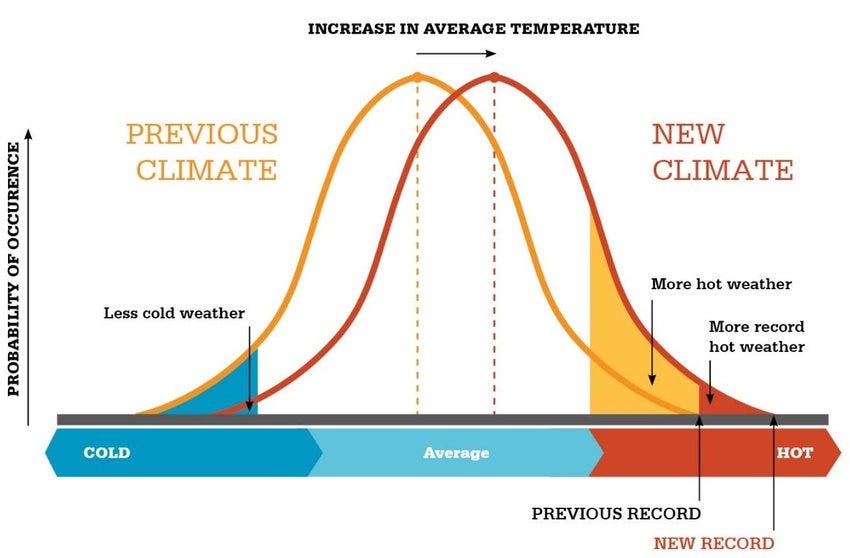

These are questions that TLP was not directly setting out to answer, so it is unsurprising that I do not find their answers in his work. TLP was, as the name suggests, a psychiatrist. There is a great deal of misery in a society, and TLP’s concern was for the miserables, not airy predictions. When evaluating his claims about the narcissistic society, though, I am reminded of a common and ever-present statistical dictum: small changes in means lead to large changes in extremes.

When a phenomena is normally distributed, a small change in the mean value will lead to much higher incidence rates at the edges, increasing ten-, hundred-, or thousand-fold based on how far from the mean you are. And I wonder, sometimes, to what extent this describes the shift in American society that TLP talks about: is it a qualitative shift in our self-conception, or a incremental growth in narcissistic desire which leads to great changes in our most visible excesses?

I wonder whether TLP is to some extent tricked by his own trade. At times, he sounds a bit like a divorce lawyer who believes that there are no happy marriages. TLP’s discussions of culture—especially advertisements—are his strongest evidence of wider cultural tendencies. But, like the Hunger Games example above, I believe his readings are weakest in fiction and pop culture. Even though they are generally stronger in journalism, politics, and individual cases, it’s still not clear how general a shift they demonstrate.

Yet wouldn’t it be more contrived to say that fifty years of narcissistic chattering classes caused no change in mass culture? no general shift in self-conception? Changes in quantity and changes in quality are not so easily delineated.

My main point of departure with TLP on these grounds is I think there were good reasons for the generational shift underlying the culture of narcissism (though I admit it increasingly overstays its welcome). The deference and self-abnegation of pre-1960s America could not deal with Jim Crow, government overreach, sexual oppression and repression, Vietnam, and all the other myriad issues of postwar America. Concomitantly, I think that these things will change/are changing on a social scale, though I am not sure if the direction is good.

However, even this might be more a difference of approach and purpose than content. Society-wide speculation is not really the heart of TLP’s theory. One of the problems with such speculation and analysis, for TLP’s overall project, is that it can serve as a distraction or excuse. TLP is fundamentally concerned with the individual: with you. Focusing too much on the structural, historical, society-wide explanations for narcissism is unproductive by the very theory of narcissism TLP proposes. It is an excuse. TLP is uninterested in explaining why narcissism became cultural. What matters to him is that you are a narcissist, and that is making you and the people around you miserable. So let’s take on the theory on those grounds.

On the Theory of the Individual

TLP’s theory of the individual attempts to explain why there are so many miserable people. Not why there are people in miserable situations—the social sciences can deal with that. Our world has a relative cornucopia of material comforts and personal liberties, compared to its previous lives. Yet there are so, so many miserable people. And many of these miserable people are among the more affluent and comfortable: the primary subjects of his essays are the chattering classes, media workers, economic and political elites, creatives, college students and graduates, and their ilk.

The mechanism TLP postulates is, roughly, that people become too invested in their identities. They are miserable, and rather than change (recalibrate, realize what the new situation requires/the possibilities it has, do different things), they do anything else, ruminating on dead dreams. Young adults who do not want to grow up, young lovers who do not want to mature, middle-aged people who do not want to retire, old people who do not want to accept help. Everyone can be sad. Healthy people should be sad sometimes. Unhealthy people prefer to hold onto the sadness, or the causes of it, than change—and because the world can no longer satisfy their identity (if it ever did), they seek it in the minds/approval of others.

Narcissism as “Me”

There are a lot of theories of “me, me, me” culture. TLP’s is distinctive in that it has a very particular idea of what “me, me, me” means. A lot of commentary struggles because the phenomenon is obviously different from greed or ambition or apathy towards others. For TLP, it is self-interest in the literal sense—interest in one’s self.

Sometimes, it seems like TLP wants to do away with a sense of self at all. I don’t believe we can have no sense of self at all. In fact, I’m not sure it would be helpful if we could. A sense of self is useful because it allows you to plan your future—self-knowledge allows self-prediction. TLP flirts with a denial of self, but this may be more a corrective than a claim (see this post, where he seems open to the therapeutic value of identity representation). The problems seem to begin when your identity becomes something you are invested in, rather than one more tool in your toolbelt.

I also don’t believe we can or should have no narcissistic desire. The desire to be loved as ourselves is the nut of many of our particular, interpersonal relationships. At times, TLP seems suspicious of this—and rightly so, if it is not kept within bounds9—but I am not willing to go over the edge: part of my friendships is an enjoyment of my friend qua themselves. Furthermore, narcissistic desire can be a useful motivation to better yourself: who doesn’t want to be proud of the person they’ve become?10 But again, it must be kept within bounds, disciplined in some way by a further objective.

I am very amenable to this sort of theory philosophically (see, e.g., my beliefs concerning the philosophy of personal identity). I have also absolutely hated writing every personal statement I have ever been required to submit. I have a disinclination towards status games, I want to care less about perception and signaling, I dislike thinking about and manicuring my identity. I say all this not because I think it is praiseworthy,11 but because any Big Theory About Why Some People Suck which also flatters my instinctive desires is dangerous.

I see two ways to attack a theory like this one: (1) arguing about its incidence or (2) arguing about its conceptual groupings. I have already considered (1) above, and in any case it is a less interesting question for a theory which is meant to be as personal as TLP’s. It is motivating for him, I’m sure, that he believes narcissism is a generational, cultural, society-wide malady. However, what matters to me as a reader is not how many people are narcissists but whether ‘narcissism,’ as TLP has defined it, is sound, and if so, whether that should provoke a change in my life.

The problem is that I really still have no idea what to make of psychoanalysis. There is something deeply compelling about it—there is a reason why defense mechanism, repression, neuroticism, ego, id, fetish, etc. all are still a part of our culture. I can’t help but feel like there is a ‘there’ there. But fiddling around with it feels like playing with a gun I can’t quite figure out the mechanics of. TLP says that when he started learning psychoanalysis, he started seeing people more as psychological objects, but also had more success with them socially. Maybe that is part of why the pseudonym is “Alone.”

Narcissism as Gender

One way of understanding the narcissist and the borderline are as corrupted versions of traditional gender roles: the man is supposed to be individualistic and action-oriented, a hero who does things in service to other people; the woman is supposed to be sensitive and in touch with her social circumstances, able to tune into how others are feeling and keep personal relationships stable and connected. Instead, the narcissistic man eschews action out of fear and is obsessed with his own image, forcing others to act in service to own personality; the borderline woman has no goals or sense of her own self, and is completely swallowed by her social circumstances, and needs constant social direction to give her a sense of self. What this frame implies depends on how one feels about the reliability and use of traditional gender roles. Were they true and eternal? Something real that was over-relied upon? A pure exercise of rank power and social oppression?

This is also another way to understand my friend’s issue with TLP’s analysis of The Hunger Games: he is disrespectful of (traditionally feminine) methods of action. Coalition-building, social coordination, and image-creation are all, in some gender traditions, contrasted with individual initiative and a sort of social bluntness. TLP, in this read, is just throwing his lot in with the traditionally masculine way of moving about the world, not providing a novel theory. Or, since the narcissist is, for TLP, usually masculine, TLP is policing traditional gender roles.

One can deal with this argument by granting it and say that traditional gender roles had something going for them. Another can deal with the matter more head on and note the ways in which TLP’s theory is skew to these roles: the narcissist attempts to dominate others to secure their identity (rather than being a man who was too demurely passive); the borderline is criticized for not having a strong enough sense of self (rather than being a woman who was too active or vigorous); the narcissist does not care about other people, and has a difficult time naturally thinking about them as leading separate, full lives (rather than being a man who was over-attentive to the feelings of others). The two theories might be related to traditional gender roles, but their ‘corruption’ isn’t merely leaning too far towards the other; it is something distinct and something bad in a distinct way.

Narcissism as Youth Therapy Culture

One of my weaknesses as a thinker is returning to the object level: can I think of instances? People I know? I think it’s difficult to say. Oftentimes, what people say is what they need and not what they do: a conscious focus on the importance of patience can come from people who are patient and people who want to be more patient.

The tenor of much pseudo-therapeutic talk today points towards the latter. The people I know who talk about the importance of self-acceptance and choosing your own needs before tending to others’ are usually people who feel deeply uncomfortable doing those things. They are trying to convince themselves these acts can be okay and set up social permission for them to do so. The problem I have with such language and style of thinking is how sweeping it tends to be. Perhaps that is helpful for someone pathologically self-hating, but (a) we come back to my distaste for informational strategies of overshooting the mark and thereby compromising on where you actually want to be and (b) it leaks out into the world—faster and faster it seems—and these ideas do not mean the same thing to everyone.

You can square this therapy-speak fairly easily under TLP’s paradigm. One of the things I find most impressive about the concept of narcissism is that it harmonizes our implicit panopticon-esque paranoia and fear of social censure with our explicit moral licentiousness: the narcissist is deeply concerned with what other people think, but doesn’t want standards which he could fail to live up to.

However, TLP also discusses the way that confessions and social judgment allow one to externalize the superego, turning guilt into shame: i.e., we all agree to hate each other so no one has to hate themselves. That also seems like a reasonable psychological story. With a more positive, somewhat different framing, that could be the psychological purpose of social punishment: we confess so that we can be punished, and rather than hate ourselves, our debts are paid and we can return to society (the rationale being that rather than continual hatred, there is a distinct punishment period). The externalizing story also, though, seems somewhat at odds with the licentiousness story (which, admittedly, is my own invention). And again, my concern with psychoanalysis: it is a powerful engine for just-so stories, and our abundance of facts make us unable to clearly and assuredly discern which such stories are true.

Perhaps these difficulties are one more reason to focus on psychoanalytic theories as a way to help yourself, not a way to judge others.

Misc. Takes

One aspect of TLP’s theory that I definitely subscribe to is his belief in the porous self—the way that the external world mixes with our patterns of thought. One aspect that I definitely don’t subscribe to is his family fundamentalism—I think that filial obligations are deeply important, but I still hold onto generally universalist pretensions, and I don’t agree with how far TLP takes it. One aspect of TLP’s theory I find curious is his insistence on the omniscience of other people—they know who you are, they can tell. This may be a literal claim about our intuitive senses of others’ motivations or a way of instantiating the conscience for narcissists. One aspect of TLP’s theory which I suppose is off-putting is his frankness concerning race and gender. I think a charitable read would have him talking about statistical averages, cultural/psychological types, and (especially with race) playing with an ironic distance.

All this being said, I really do find his theory compelling. A moral malaise leading to a sole focus on the self and its place in the winding hall of mirrors of social status hell.

On the Theory of the Cure

See generally: “Can Narcissism Be Cured?”

Bringing Guilty Back

TLP’s theory does sidestep one of my common problems with psychoanalytic framings by prescribing a cure: keep narcissism within bounds by having a goal external to the self. Believe that something outside of yourself is good, is more important than the self, and your concern for your self will necessarily fade. Much like how a laser focus on your level of happiness will do nothing so surely as rob you of whatever contentment you had managed to gather, a laser focus on your identity will rob you of any ability to create a sturdy, resilient, reasonable sense of self. There are some psychological constructs which should not be load-bearing, and identity is one of them. This certainly flatters my moralizing instincts, but I also just think it is correct?

TLP wants to build back up a superego, an internal sense of right, wrong, and responsibility that disciplines the ego and id. Focus on yourself and not others, on your own responsibility and requirements. Other people's beliefs and esteem should matter less to you and they themselves should matter more. Other people are not status-engines but companions.

As a moral matter, this seems unimpeachable: the problem with narcissism is that it hurts other people, and focusing on helping others instead solves that problem. As a psychiatric matter, I am less convinced. Primarily, I am less convinced because of Civilization and Its Discontents: we tried focusing on the superego, and it didn’t go well. There is, of course, a world of difference between building up an atrophied superego and relying on a dictatorial superego to repress desire and identity formation. But I wonder how TLP would balance the superego’s demand of right in a world so big with so much wrong slapping you in your face? I have made my own psychological bargains, but which would he propose?

Perhaps this explains his pairing of the focus on the superego with a narrowing of the moral scope: first, focusing on your own virtue rather than others’, and then, focusing on your local obligations and not your national or global. My very discomfort with what I called his “family fundamentalism” may be exactly what allows his solution to function ethically in such a big, big world. We can’t go back to “love thy neighbor as thyself,” but we can at least get back to “love someone.”

Another distinction might be his hope for a reinvigorated id which features more prominently in Sadly, Porn, his book. This, though, is a review of the blog and not the book, which came out several years after he stopped posting on his blog. Perhaps I will get around to reading the book at some point, but here I will simply note that some of the reviews I have seen of it seem to indicate that it points in this direction.

Therapy as Cure, not Palliative

Some people read about the ins and outs of plane engines despite never going to engineering school. Some people consume fountains of content on professional sports they have never played a day in their lives. I read about therapy despite neither going to therapy nor formally studying psychology

TLP is very critical of his own industry. Some of this is unrelated to narcissism, and more about his criticisms of scientific methodology more generally (some of his best work ancillary to his narcissism posts are analyses of the assumptions and institutional incentives in psychiatry and science more broadly). Elsewhere, it is very much related to narcissism, and he charges many in his industry with providing a service which allows narcissists to remain the same rather than providing a cure which requires them to change.

TLP is not interested in palliatives: he wants a cure. Therapy as it is often practiced—talk-based insight therapy—is anathema to TLP’s theory of the cure. For him, you can only change when you act differently. No insight will change you. It is perhaps a corollary to the old quote, “if arguments were enough to make men good, they would justly have won great rewards” (if psychiatry were enough to make men good. . .). The search for insights becomes an excuse not to change the things you do.

I do think there is something to this, in the converse: it may be that insight therapy works by having insights provide an excuse to change. For instance, note that Freudian psychoanalysis works about as well as our more modern therapeutic theories. This is difficult to explain for any party who believes that the truth of a therapeutic theory should bear on its effectiveness and that we have at least one therapeutic theory that is more true than the others.

Another note: the efficacy of CBT, as with many other therapeutic theories, has declined over time. Various forms of therapy get less efficacious as they “enter the water supply.”

For more: see Book Review: All Therapy Books.

There are lots of ways to square all of these findings,12 and Scott Alexander gives able theories as to how to deal with them. But here is how I would expect TLP to do it: all therapies work by providing an excuse to change, and insight which gives you permission to actually just be different. All the ones that bubble up to the top are about as good as one another at doing this, but as the theories propagate through the culture, they become less novel. This lessens the primary purpose of the therapist in these cases: to provide a novelty which becomes an excuse to change.

This is a pretty deflationary account of insight therapy coming from within the halls of insight therapy—indeed, from its progenitor: psychoanalysis.

To the extent that these insights actually do cure people, I’m sure TLP would have no problem with them, but he does seem to believe that many regular therapy-goers, for whom therapy is a consistent activity with little or no plan to stop going, are using therapy as a palliative that allows them to live with their lives rather than a cure which could help them get better. The drugs, the therapy, and the venting are ways to make it easier to change. Or easier not to change! But that is up to you: the important thing is to remember that you have to change.

On the other hand, palliatives for mental health are really important. As an old Tumblr blog notes, we need to sing about mental health. Suffering is really, really bad, and alleviating it is good—it is a stupidly correct claim, but one of which we should always be reminding ourselves. It is a thin line between finding solace in a terrible situation and becoming invested in that terrible situation. Part of it comes down to this: it’s not clear whether TLP believes in an incurable mental illness. If all mental illness is curable, then solace in the situation is inevitably just a way to prolong it.13 Or perhaps he just thinks it is deeply counterproductive for narcissists and such to entertain that possibility.

The Style

One of the things that is immediately noticeable about TLP is his distinct, abrasive style. This style seems more prominent in his posts about narcissism and also more prominent later in his blog than earlier.

These trends could be the result of increasing frustration, as he perhaps began to see his work on narcissism not have the effects he had hoped. One post on the subreddit dedicated to TLP’s blog hypothesized that this was why he stopped blogging, but there are others who say that he got doxxed and his work didn’t like the blog. It’s also possible that he stopped blogging to focus on writing his book.

It may be more fruitful to consider the style as a strategy, whether intentional or not. How might this alcoholic and cynical persona with its critical, insulting, second-person style help or hurt his overall goal of moving his readers away from narcissism?

A first theory might be that because TLP believes that the culture is deeply narcissistic, a hermeneutics of suspicion is necessary. However, a reserved tone won’t create the visceral suspicion towards such cultural ideas. Therefore, he needs to model suspicion both in argument and in affect. This would explain his cynicism, but perhaps not the second-person direction.

A second theory could be rest upon TLP’s theory that a big problem with narcissists is the lack of a superego providing a strong, internal sense of right and wrong. Therefore, the rancor and abrasiveness that characterizes his style, especially in his later posts on narcissism, combined with the second-person object, is a way to shame you—you—into having a superego.

Furthermore, a problem with treating narcissism is transference: the narcissist learns to adjust their behavior to gain approval with their psychoanalyst rather than learning to develop a proper superego.14 I believe that this is a very strong argument in favor of pseudonymity (as TLP himself notes), and also a very strong argument in favor of TLP’s best psychiatric prescriptions: fiction-provoked introspection15 and older works of art.16

As it relates to style, perhaps the constant disapproval aimed to undermine the natural process of transference: if the disapproval is constant, approval cannot be the aim. However, as some note, this can go the other way too: constant widespread disapproval, especially from a clearly skilled and (niche-ly) high-status individual, can make people desire that person’s approval even more, as it becomes more scarce and valuable. In this way, it could backfire, as narcissists are particularly prone to the desire to be led by an authority (or at least an authoritative figure, which TLP certainly positions himself as). It is also exceptionally easy to except yourself from TLP’s slander, so natural that I sometimes start doing it without realizing. “Yes, he’s referring to all his other readers—not me, because I get it” (or some other such excuse).17

The style could be simply a rhetorical strategy, as it surely to some extent functions as. As a critical review of Sadly, Porn put it: “he builds tension, criticizes, berates, makes you think everything is brutal and painful and without point and no solution, and then he gives you one. He makes you ache for a point, and then provides one.” In this way, the style acts out its own critique, with knowledge stepping in for action, and providing permission from a (pseudo-)authority.

In my most galaxy-brained of moments, I imagine it as a Xanatos Gambit leading everyone to his preferred outcome: desperate for his approval? Act in a more considerate way to align yourself with his teachings. Get turned off by his aggression? Try to prove him wrong by acting in a more considerate way. Or get convinced purely by his arguments and actually act for others. Get suspicious of his rhetoric? Inoculate yourself to the allure of authoritarian permission and define your own sense of right and good and desire and value.

A Sharp Mirror

It is curious that TLP chose “Alone” as his pseudonym, when his mantra is to love and care about people other than yourself. The critical review I mentioned earlier discusses the fact that, in Sadly, Porn, TLP talks about how he can’t connect with people and never feels like he is in community. In this way, the critical reviewer’s review is spot-on because he has already internalized the lessons of Sadly, Porn and therefore has no need of them: screw this guy! He’s not an authority. He’s not God! But many people don’t have a god, unlike the author of that review, and go looking for one. The situation reminds me of Sam Kriss’s idea that Nietzsche wrote excoriating the resentful for the resentful:

The obvious answer is one philosophers have a strangely hard time comprehending, but almost every fourteen-year-old who’s picked up a book of Nietzsche’s has instantly recognised. When Nietzsche talks about master morality, he is not talking to the masters; he’s talking to the weak and the botched and to pimply Jimmy: to the slaves.

According to his myth, master morality is the natural creed of the free, strong, noble peoples of the world. Eventually, though, their victims banded together and decided that strength and nobility were evil, and the best thing to be is harmless and meek, and slave morality was born. Like all great and true myths, this one bears no actual relation to history. There never was a tribe of blond beasts practising an ethos of pure cruelty. It’s master morality that was invented by the weak and the botched—by one particular weak and botched individual, which was Friedrich Nietzsche. Its isn’t to compensate for his weakness. Nietzsche insisted he was strong, but he was always very specific about what his strength was made of. ‘I always instinctively select the proper remedy when my spiritual or bodily health is low; whereas the decadent, as such, invariably chooses those remedies which are bad for him.’ Master morality is a remedy by and for the weak.

If I may do some slapdash speculative armchair psychiatry of my own, I would guess that TLP himself has a very difficult time loving people, and very naturally thinks of himself and others as having roles in a story. He mentions, at one point, that the way he brings in a variety of arguments and perspectives to his internal deliberations is to pretend that he is another character or person and imagine what he would say if he were them. He mentions at another point that he has felt like he objectifies people more now, with the tools of psychoanalysis, even as they like him more, and that leaves him Alone. He mentions in another place that he naturally and often thinks about people as their roles.

The point of all this, however, is to care less about the man behind the words and think about the words themselves. Maybe the character of the author can teach you something, but fundamentally the words are the words, and their purpose is to ricochet you somewhere closer to the truth. The words give you possibilities. Maybe there is information in the author as well, but take the words first. What do they mean to you?

Perhaps thinking too much about the person is even narcissistic: why are you thinking about what they did and not what you can do?

Perhaps, then, TLP’s style sharpens the narcissist’s dysfunctional relationship with authority: either they are goaded to accept this new authority and act differently (which is what TLP wants in the end—action), or they reject the authority and hopefully begin to learn how to set their own standards. The worries are that either (1) they except themselves from TLP’s barrage, mentally substituting “you” for “they,” the reader themselves for the unsophisticates who don’t even know they’re being manipulated by the culture or (2) their identities are threatened by TLP’s rancor and they ignore him for the affirmation they can get elsewhere.

There is also the third option, which TLP responds to consistently when he reacts to reader comments and messages: that narcissists continue to misunderstand the thrust of what is wrong because they keep trying to reformulate it in terms of identity and themselves, rather than action and others. But this is no fault of the style, just a failure mode of the project in general, and the difficulty of getting people to understand a fundamentally different level of analysis.

Action Replacing Identity

The core of TLP’s theory of the cure is that action (what you do in the world) must replace identity (what you are):

"But I want to change, I want to get better."

Narcissism says: I, me. Never you, them.

No one ever asks me, ever, “I think I'm a narcissist, and I'm worried I'm hurting my family.” No one ever asks me, “I think I’m too controlling, I’m trying to subtly manipulate my girlfriend not to notice other people's qualities.” No one ever, ever, ever asks me, “I am often consumed by irrational rage, I am unable to feel guilt, only shame, and when I am caught, found out, exposed, I try to break down those around me so they feel worse than I do, so they are too miserable to look down on me.”

If that was what they asked, I would tell them them change is within grasp. But.. . .

“So all is lost?”

Describe yourself: your traits, qualities, both good and bad.

Do not use the word “am.”

Practice this.

(Source)

In one way, this change makes you far more of an individual: action is, and must be, individual. We can coordinate, and that is wonderful, but what you do, in the first instance, you do fundamentally as an individual. With this, you are focused on what you can do: not so much others, except perhaps as a strategic consideration. Your identity, on the other hand, is a matter of collective definition and appearance. Consider the influential philosophical theory that we learn self-consciousness through our confrontation with other people: identity is the practice of forming and determining perceptions, which always require another set of eyes.

In another way, this change makes you far less of an individual. Action is directed outwards: into the future and/or out to somewhere beyond your immediate self. It is directed at other people (including, oftentimes, your future self). In this, action’s goal is to touch others. Identity is the perceptual determination of how we as ourselves are distinct from others and compare to them. In this, identity’s goal is to distinguish us from other people.

The psychiatric problem of narcissism is that identity is not a very good defense mechanism. It forces you into a totalitarian relationship with others, managing their perceptions of you in order to feel affirmed, and cuts you off from those very others because your central concern is not how you can impact them but instead how you can be distinct from them. As the Stoics said: “Things in our control are opinion, pursuit, desire, aversion, and, in a word, whatever are our own actions. Things not in our control are body, property, reputation, command, and, in one word, whatever are not our own actions.” All of these things can be defense mechanisms (or sublimations, or whatever)—everything is—but I certainly throw my bag in with TLP on this matter: action and contact, chance for failure though they bring, are made of much sturdier stuff than perception.

There are other odds and ends, some bits of practical psychological know-how that crop up relatively frequently in TLP’s work. These are quite often incisive. One of my favorites comes in his review of Shame: if you are trying to stop doing something, don’t refrain, but instead fill your head and time and habits with other things. Become a person who does different things, thinks about different things. You can’t just open a space, because it will get filled in by what was before. You have to create something new. Many of his posts are worth reading purely for these gems.

On the Theory

TLP’s theory of narcissism is a great tool in your conceptual toolbelt. Once you have this particular hammer, a lot of nails start coming into view. Sometimes I want to grab people (including myself) and scream “why do you care so much about what other people are doing?” “Why are you never the problem?” “What are you going to do about this?” Yes, complaining and gossiping and commiserating can be palliative, and there’s a place for palliatives, but if our whole lives comprise one long senescent decline in palliative care, what are we even doing here? It’s a way to live, but even when it goes well (and it doesn’t), it’s a sad one. Is it surprising that in such a life we might feel empty or useless? I think sometimes our faces should be rubbed in what it is we’re choosing to miss out on: failure, embarrassment, sacrifice, guilt, responsibility, . . ..

Individualism and Social Change

Of course, like all tools, it is important to use the theory judiciously, but that’s not so much a critique of this idea as it is of ideas per se. I think this one comes with good instructions for its use: if we find ourselves thinking too much about how everyone else is so narcissistic, we’re missing the point as defined by narcissism. Instead of using narcissism as a way to distinguish ourselves from others in a made-up status game, we must use it to better care for and love each other, broken little narcissists though we may each be. This is another reason why I am less enthused about the societal imprecations of TLP’s theory: it sits uneasily beside the undercurrent of personal responsibility and care. I understand that the societal stuff feels more important, bigger, etc. And maybe it is, especially if you find it persuasive. But the esoteric readings of popular movies and political debates can distract almost as much as they elucidate. I’m not sure it would be better to do without them, but a warning is necessary: they are not your excuse.

I think his discussion of ‘the system’ runs into a similar issue of being possible fodder for excuses. I don’t want to get too deep into discussing his ideas about ‘the system’ or politics or history because while they are connected to his ideas about narcissism, they are distinct and would require even more writing in this already long post. Instead of evaluating it directly, I will note that it makes an uneasy bedfellow for the sort of solution TLP is most directly charging at: focusing on your own actions and obligations rather than impersonal or external forces you can use as excuses. It is entirely reasonable for TLP to have multiple goals with his blog, but I want to note the tension.

PJ Vogt’s podcast Search Engine did an episode on jawmaxxing recently, which is the practice of working out your jaw by changing your diet or direct exercise under certain theories that modern processed food create our dentistry problems by giving us atrophied jaws that shrink our space for teeth and so on. One point made in the episode is that America (perhaps especially in more recent times) has a tradition of a sort of individualist antimodernist (or supramodernist) solutionism. There is a strain, they argue, especially present on the internet right, which is critical of the changes brought on by modernity and seeks to solve them through individual efforts.

TLP, I think, to some extent falls into this camp. And I’m not entirely sure that such a camp should be derogatory, per se. We ought to understand modernity, and it is not all good things—that is one way we improve modernity. Furthermore, we act, to a fairly fundamental extent, as individuals. For change to happen, it must happen on the level of the individual. Also, these online communities may be premised on individual change and excellence, but they are online communities. They have common beliefs and social ties, just through the internet (about which there are, ahem, pros and cons).

My point is not that there is no need for such communities or ideas, but that they fit uneasily with critiques of systems and society. TLP’s is fundamentally an individual, psychiatric theory. There isn’t really a theory of social change to go along with it (other than, even in his words, the change of generations). Now, the theory of change could be individual evangelism of TLP’s ideas—simply spreading the good word by speech and example. I suppose I am to some extent doing that myself. But that’s not really present in TLP’s writing: he doesn’t command his followers to “[g]o therefore and make disciples of all nations[.]”

What you are left with is cynicism about society and a belief that you can be better (than society (because you know what’s wrong with it)). And that concerns me. It plays on traditionally conservative ideals of individual excellence and elitism but without the usual concomitant restraints of resistance to change and humility before tradition. It is critical of milquetoast liberal society with an undercurrent of pushing for radical change. It depicts the large swathe of society as not free or in some sense real people, but mere subconscious instances of ‘the system’. These are—and I am trying to say this in the least inflammatory way possible—similar to emotional and ideational tendencies that fascism tends to play on. That isn’t an argument against the ideas rightly construed! Or even the ideas themselves! But I think it is the clearest picture I can give of how the ideas can be used poorly.

I am, at heart, a squishy, humble lib. For all my edgy posturing, esoteric commitments, and flirtations with strange ideas, at heart I’m not so arrogant to try to decide too many things for people—especially without some sort of agreement, consent, or other legitimation. The hermeneutic of distrust and suspicion which TLP practices so well, while valuable, is not a place I naturally equilibrate. I believe too little in the power of my little words and too much in the wisdom of crowds, of which I am just one (sometimes helpful, often contrary, perpetually niggling) part.

Psychology and Prophecy

Something that I haven’t really touched on here yet but really should come up somewhere is just how enjoyable these posts are to read—at least to me. Take the jibes and political/gender/racial faux pas just a little less seriously and it’s an absolute joy to read. His rhetorical skills are excellent, prophetic in the oldest way imaginable: he’s trying to rub our faces in our own lives. He wants to sharpen our contradictions and he just does it so well. The conversational tone, the well-phrased rhetorical questions, the striking illustrations—all excellent.

This blog has recently moved in somewhat of a psychological direction. I think that is in decent part to do with the influence of TLP on my thinking and the way I have reacted to his ideas. It has helped to try my hand at this style of thinking, as TLP was my introduction to psychoanalysis even as it was a very particular method of employing it—this late-2000s blog isn’t really a canonical source of psychoanalytic theory. I think TLP’s influence on my post “You Don’t Think it’s Good to be Good” is fairly evident, and “Moral Masturbation” also probably owes much to TLP.

I might have one or two more posts in my back pocket that will deal with these themes for now, but after that I’ll probably be putting away this toolkit for a little while. I find psychological speculation and analysis unsettling, and I think it should be used as most medical interventions are: to solve a problem once you have identified it as a problem.

I have stated this before, but perhaps never in so many words: everything has a psychological explanation. Within a psychological theory, all proxies are fetishes; all habits are some form of perversion or neuroticism; all beliefs are rooted somewhere in the id, ego, or superego; and all motivations come from some basic desire. If they didn’t, it would be a pretty bad theory! However, we often assume that the psychological explicability of a belief or behavior as, e.g., a neurosis bears on its validity as a general claim. But there is nowhere to stand outside of our psychology! The psychologist, by reducing an behavior to a psychological phenomena, seems to place themselves, their theory, and their behavior outside of psychology. But that is merely an illusion.

A psychological theory is nihilist. It probably should be nihilist, in the first degree: follow the truth and describe it. We usually expect scientific theories to be nihilist in the first degree. However, because psychology bears on humanity, our behaviors, and our beliefs—the only sources of values you are liable to find in the world—its nihilism is particularly acute, and can, if we let it, swallow us up. That doesn’t seem right to me. First, like all sciences, psychology is limited in its power and scope: it is a lens. Second, psychological explicability should not bear on philosophical value. One can probably describe my beliefs surrounding climate change through my experiences with authority as a child, my political tribal affiliations, and many sources of psychological mechanisms besides. Does that make you want to bet against me on it? I would hope, for your sake, not. Why should it be different for philosophical values?

First, we must evaluate a behavior on philosophical grounds: is it good? bad? right? wrong? is it harming the actor? is it harming others? are those harms good or bad? etc. Only then, once we have determined that a behavior or belief ought to be changed, we call upon psychological theories to give us insight on the terrain. All of human life is a bundle of knots. Some knots hold ships fast and shoes tight, while others tie us to cinder blocks. It can be an interesting academic exercise to call one knot a boom hitch and another a double windsor, but you only start pulling at loose ends and trying to map it out (or, god forbid, break out the scissors) after you determine you don’t like what the knot is doing.

One reason I like TLP especially is that his psychological theory is explicitly laden with and attached to a moral vision. The ethical force and direction is directly there with his psychiatric prescriptions: he is telling you that you are externalizing your guilt in order to convert it into shame you can ignore and that your doing this is loosening important communal norms. As much as he is trying to sharpen the choices we are making, the ethical valence is clear. That is, in fact, his point: he wants to draw our attention to the choices we are ignoring or downplaying precisely because they are ethically uncomfortable for us. If we find these choices incompatible with our moral beliefs, we can get on board and try to change. If not, then we’re not the target audience.

Some writers or written works are valuable because they give you clear and correct insight into a problem you are aware of. I do not believe that is the primary value in reading TLP. Rather, at least for me, it is the discovery of an entirely new paradigm with which to recontextualize things. We are limited thinkers, all of us; we only have so much material to draw on. Finding weird theories, new theories—theories not opposing the ones you know but rather skew (see VII.) to them—is a sort of freedom. It is the freedom of having more worlds of thought to choose from, to mix and match between, and to compare to one another. The canonical greats are often valuable because they created their own worlds, these vast new sketched expanses to be filled in by later generations. But you can also find little worlds in stray nooks and scattered crannies, in niches impenetrable by limelight and long-running conversations three steps removed from polite society. You can find them, indeed, in the corners of the internet.

Apropos of little, there is some evidence that the processes of supporting and refuting ideas use different neural processes.

An aside: you know who never tried to exterminate the Jews? The Ottomans, the Russians (under the Tsars, at least—just some pogroms), and all the other undemocratic, conquering empires. They didn’t have to be nations. They didn’t have to forge a common feeling out of so many people. No subject had to be concerned for whom this strange, insular people would vote. It was in the process of democratizing that Germans got so paranoid about their fellow citizens that they attempted to murder each and every one of them.

These links can also give you a sense of the conservative movement towards narcissism, as I have given a story of the liberal movement towards narcissism.

The new political formations were already being commented upon before Nixon by Richard Hofstadter in his essay “The Paranoid Style in American Politics.” You can see commentary savaging the other side of the political aisle in “A Letter to the Young (and to Their Parents),” which is a neoconservative’s take on the New Left. Boorstin’s “The Decline of Radicalism” precedes some contemporary complaints of the impracticality of the modern left.

A note as well on the neoconservatives: especially early on, they were, generally, the Cold War Liberals, oftentimes Marxists as youths, holding onto the old liberal communal ethic and aghast at the wantonness, lack of sense of responsibility, individualism, and obsession with racism their younger counterparts exhibited.

Throughout the 1970s and 1980s, the old guards of the Democratic and Republican Parties fall away, and the new way of doing things makes its way up the chain.

One way, perhaps, these things might become pathological is that, as the reaction becomes the norm, the original is forgotten (or is no longer practiced), and so the natural combination of the two which made the newer way of doing things appealing fades away, and only half the picture remains. This, however, only helps conceptualize the way in which these trends recur, and not the ways in which they progress.

This is an underrated way people misunderstand age-based polling and datasets. “How strange is it that 18-25 year olds are voting so differently from how they were 8 years ago.” No! Not strange! That is a 100% different group of people!

The idea of creating white-collar “superstars” is that, e.g., computer programs allow a very good accountant to use their expertise and excellence to create more difference in value than without such programs, because bean-counters and human ‘computers’ gum up the efficiencies. This also, of course, follows for entertainers and the ability to stream performances.

Matt Yglesias likes to say that the cultural critics of television who were saying that it made us lonely and alienated were right, just early.

Or even because I believe that these desires and behaviors and beliefs are not on some level further plays in a bigger, grander status game (but if you would like to praise me, please do).

One thing to note as well is that different theories may work for different people. Alcoholics Anonymous famously fails some randomized control trials, but that is likely because its program only speaks to certain people. Without it, there would be an overall decrease in the efficacy of treating alcoholics, even if we can’t be sure that any random alcoholic would be helped by it.

I am unsure how to square with this theory that it seems like Freud believed the superego was an internalization of external authority.

I am becoming convinced that the only real way to “personal growth” outside of direct action is through careful study of fiction. Of course stories may have an intended meaning, but a well written story allows you to ask not just “what does the story mean?” but “why do I think that this is what the story means?” (Source)

I am nervous about recommending “the Classics” because it sounds contrived and pretentious, but anything that has withstood the test of time and is not something that was created to be consumed by current narcissist adults is as good a place to start as any. (Source)

I remember hearing a media figure say recently—maybe it was Ezra Klein or PJ Vogt—that the people they knew who seemed to keep their heads on straight the most the last ten years or so were the ones who had stronger roots in older, more untimely media. I believe the benefits of such anachronisms are numerous and profound. At a first gloss: any broadening of the conceptual horizons is extraordinarily important for allowing you to see the water you and everyone else swims in, and one of the most prodigal avenues of strangeness is time—the past, as they say, is another country, and there are quite a lot of them.

See, e.g., this bad review of Sadly, Porn which conveniently finds that TLP’s analysis of dysfunctional masculine psychology is actually not really on point, while his analysis of dysfunctional feminine psychology is super spot-on and generally applicable. Surely this is unrelated to that guy being a dude and disliking feminists.