Why the Neoprogressives Are Coming

Making the rational (somewhat) real and making the real (somewhat) rational

This post is the third (and final) post in a series on a theory of the direction of contemporary politics through a historical analogy to the dawn of the Progressive Era. See post 1, 2.

“Discovery games” are games where participants are unaware of the rules and must deduce them from some sort of external judgment. One such game is eleusis. In eleusis, players attempt to place cards on top of other cards. Only one player knows which cards are allowed to be placed on top which other cards, and can stop the other players from doing so when they don’t follow the rule. The other participants want to figure out that player’s rule.

What makes these games hard is not finding a theory which fits all the plays that have been allowed or denied, but that there are too many such theories. A rule can be that you cannot play a card of the same suit as the one before. A rule can be that any card can be placed down while you are standing up, but only black suits can be played while you are sitting down. A rule can be that you can only place a card after complaining about the rule. The steady elimination of such theories requires repetition of the same process over and over and the steady elimination of extraneous facts.

This is, to a large extent, our relationship to the world. We presume that there are rules, but we can imagine too many possible rules. The problem is that there are too many facts and you don’t know which ones matter. Science gives conclusions not by accumulating theories or facts, but by ruthlessly excluding more and more facts, and therefore more and more theories, until the causal mechanism is clearer.

The trouble with historical theories is rarely that we do not have enough facts, but almost always that we have too many. The process of choosing which facts matter is fraught. Different facts teach different lessons.

“The Supreme Court, beginning in the 1950s, began expanding the sphere of constitutionally-protected rights in several highly contested areas. Now, its legitimacy in surveys is lower than it has been in a long time.” Or, “Across the world, socially destabilizing forces which have brought on a new level of cynicism towards established institutions. Now, the Supreme Court’s legitimacy in surveys is lower than it has been in a long time.”

Both of these say true things. But which connection is more effective? I think the latter, but that relies on a lot of my background beliefs concerning global trends, national differences, political legitimacy, rising expectations, and media environments.

The facts you are interested in depend on your theories of what facts matter, and the theories you use to guide your inquiry depend on the facts you have available.

The first post in this series used a specific instance of political strategy—the Brandeis Brief—as a synecdoche for Progressive politics, and used that to help distinguish modern movements into roughly neoprogressive and neoabolitionist quarters. The second post in this series distinguished the original progressive and abolitionist movements by looking at their methods of interaction with the political system, and distinguishing them along ‘political’ versus ‘parapolitical’ lines.

In this post, I’m going to compare the issues by which we chose to define the last 50 years and the ones by which we are shaping up to define the present. I want to distinguish between them in two ways: (1) the different sorts of solutions they required or seem likely to require and (2) the different opportunities afforded by their political economies. When it is fruitful, I may bring in analogical issues from the Progressive and abolitionist eras to further refine or complicate things.

This method of reasoning is somewhat Panglossian: that, when faced with problems of a particular character, people will adapt to that character in order to solve them. But I deny that it is fully so. The theory itself takes no stance on whether this definition of the true problems of the age is good or bad: the process by which we decide with what it is we are concerned is beyond the scope. In choosing the problems that I expect to define our future decades, there is some room for wishful thinking and the influence of beliefs extraneous to the argument here. Maybe you agree with some of my political-cultural analysis and disagree with the rest; I hope to at least provide a shape of something.

The virtue of this methodology is that I believe it is far easier to pick out the underlying material and social problems people are and will be concerned with than it is to predict the many winds of culture as they wind from one view to the next, creating little tornadoes of cross-breezes and pockets of circulation. Hopefully, the consistency in the form of my analogies will constrain the degrees of freedom these sorts of analyses suffer from, and provide some sense that I am not simply stacking epicycles upon epicycles. Once we have the shape of things, I’ll summarize what I see as the very rough, long-term predictions of this theory.

The Neoabolitionists and Neoprogressives

Here’s a fun game to play: whenever you see a trend that started around the early 1970s, assume that now people are saying might be reversing (you can also do the reverse). How are often you wrong? You will be right more often than you may expect.

This pattern exists in particularities and niche concerns: the early 1970s heralded a shift in the medical profession away from paternalism to a model of the doctor giving you a bunch of information about the operation and then leaving you to figure it out, but now there is a burgeoning model of collaborative decision-making where you and the doctor decide together the best course of action.

It is also true of general US trends: income inequality, which started rising in the early 1970s, has been falling for a little while now; the hip young conservatives are no longer Goldwater-esque antigovernment libertarians that burst onto the scene in the late 1960s, but instead nationalists inspired by a guy obsessed with William McKinley; and the reformist project of the latter half of the 20th century is running out of steam.

At least, that is my contention.

After the Progressives came our contemporary, currently-dueling set of reformist movements: the general constellation of social and legal movements in the latter half of the 20th century that I call the neoabolitionists and the now-forming set of ideas and institutions that I call the neoprogressives. The last post was a stylized history following a thread of American society from the dawn of the abolitionist movement in the antebellum North to the end of the Progressive ideology in the postwar youth. Now, I want to use an issue-by-issue comparison of the problems by which people defined the 1970s and the problems by which we are poised to define our coming decades for two purposes: (1) to further demonstrate the distinction and (2) to help explain our recent political pathologies and point towards a more adaptive path.

Sexual Orientation and Gender Expression

I want to start with this one because the distinction is clear, sharp, and pertinent: LGB on the one hand, T on the other.

The transgender rights movement is generally considered continuous in some manner with the gay rights movement preceding it, but its prominence is novel and arose after the culmination of the gay rights movement. For the purposes of this analysis, I’ll be referring to them as separate movements, even though many of the organizations, people, and ideas have been carried over from one to the other.

The objectives of the two movements have strikingly different characters. The gay rights movement had, functionally, three laws it wanted: legalize sodomy, gay marriage, and gay adoption. It further wanted general social acceptance of gay relationships. All of these laws are administratively and epistemologically simple: stop enforcing this, allow two men/women to put their names on that document, and allow two men/women to put their names on another document. The trouble was with social norms and moral/religious ideas—the problem, fundamentally, was with legitimating a choice. To deal with this problem, an identity was fashioned: a gay man, or a lesbian woman, who was born that way and must be allowed to express their true identity, as any American should have the right to do. Identity, incidentally, became very important in the 1970s as a concept socially, culturally, and philosphically—much less so in the preceding decades.

The trans rights movement has goals as well. But, as I think most people can in good faith agree, these goals are administratively and epistemologically complex. While the law of marriage largely concerns the property of the two married individuals (with some bonus perks like having the authority to make certain medical decisions), huge swathes of American society are organized by sex and gender, often without consideration of which is relevant. Should trans women be allowed in female prisons? Who decides whether such a request is made in good faith? What about women-only domestic abuse institutions? Should trans men be required to join the Selective Service System? And I do think the women with serious concern for the hard-won respect for high-level women’s sports which they, with rational basis, believe could be endangered by biological advantages in trans women are deserving of consideration.

The point is not that these problems are too difficult and we should throw up our hands and forget about trans people (or demand that in all cases self-asserted or perceived gender identity controls), but simply that these are highly complex and context-dependent political and social determinations. They turn on what is important about gender as a social tradition, what is important about sex as a biological phenomenon, and what is important about these activities.

It is true that there are many transphobic people, who simply do not respect trans people and their decision to change their gender. I don’t believe I am one of them, and I try very hard not to be one of them.1

There is also the further difficulty of transitioning as a future commitment and a stable identity. Even if you don’t believe my strange ideas about personal identity (which I will return to at some point), you can at least understand that we are imperfect at understanding our future selves, and when we make commitments which jeopardize our future well-being, we ought to make those commitments with as much foresight as possible. Children do not have as much foresight as is possible. But with gender identity, time can be of the essence! Puberty blockers don’t work after puberty—but puberty doesn’t work after puberty blockers either! These are tricky determinations: who is allowed to decide to castrate someone, even themselves?

A sturdy basis of transgender rights will require good-faith experimentation, compromise, and incremental progress. As lacking as these things seem today from all sides of the trans rights issues, the problem won’t change: only we can. And the problem points to state and local experimentation, legislative dealing, and broad-based support. Contrast this with the judicially-focused, binary quality of gay rights: some states passed bills, but in many places (including its eventual national enforcement), gay marriage was a matter for the courts, not the legislature.

Sexual Mores and Gender Relations

The 1970s brought the sexual revolution in response to the continual repressiveness of communal norms around sex without respect to technological change in contraception. Along with the neoabolitionists’ general distaste for prudishness and deference to community, the sexual revolution promised equality by letting women have sex. Women can make their own decisions, go into the workplace and get education—they can do whatever men can do, so let them do it! And that is all true!

Strange, then, that the kids these days are such prudes. They’re not having sex, they’re uncomfortable with sex scenes, and they’re crying out for a decent, humane etiquette of romance and sex. But the only conceptual tools that survived (indeed, were forged by) the sexual revolution were “consent” and “rape.” So they work with what they have! In addition to all the actual rape and rape culture and sexual assault, they call all sorts of difficult, compromising, muddy sexual interactions rape or “rape culture” or sexual assault because there’s no vocabulary for gradations and types of disrespect or decency beyond consent.

The neoabolitionists were rebelling against repressive communitarianism for a culture of tolerance and free individuals, while the neoprogressives are trying to forge some sense of common standards out of freefloating, tolerant individuals. For an example of budding discontent with the post-sexual revolution script for young women, see Would You Rather Have Married Young?

Again, here, this is something of a distinction between loosening old rules (simple and directional) versus forging new ones (complex and iterative). Every time a group of girls complains about noncommital situationships and tries to figure out what they want and how they should try to get it, or a group of guys tries to figure out when and how it is appropriate to approach a girl and whether it’s chauvinistic or just polite to pay for the first and second dates, they’re doing something (sigh) political. Or at least social.

For those in committed relationships, the neoabolitionists advanced no-fault divorce and equal rights within marriage. I think the trouble on the horizon for marriages now is sports gambling—which has been so bad for families that you can see foreclosures on homes rise after it is legalized in a state. This dynamic of men betraying their family finances due to a newly-accessible vice has far more in common with the temperance movement’s reaction to cheap, industrialized alcohol production than the 1970s women’s rights movement’s reaction to wives without an exit option or forced to stay in a loveless marriage for fear of social opprobrium.

I will also note that the 1830s to 1850s, with the American Renaissance, coincided with a big cultural and artistic taking-to-task of American prudery by Whitman and Co.

Housing

Speaking of foreclosures, we’ve got new housing problems. The neoabolitionists railed against the deracinated, stifling, “little boxes” of suburbia; the racist impacts of redlining and HOA compacts which didn’t allow sales to people of certain races; and uninhabitable apartments with inattendant landlords. They had more success with the latter two issues, though our contemporary legal derogation of mobile homes could be downstream of the first. On the latter two issues, major solutions included the Fair Housing Act, which outlawed discrimination on the basis of various identities with respect to selling housing, and the warrant of habitability, which gave various implied assurances to tenants about the quality of their housing.

The themes here are distaste for stifling conformity, legislating rights to not be discriminated against (to be judicially enforced), and setting legal minimum standards.

The problems we face with respect to housing are very different: the problem we have focused on now is not the quality of housing, but the price. We just can’t build it. If anything, the neoabolitionists were averse to mass developments (see “little boxes”) which, though not very quirky, did provide a roof and such for a pretty good deal.

The battle lines are different now: most principally, the profit motive is largely (but perhaps not totally) on the side of the reformers. Before, the enemies of the reformers were racist owners, bigshot developers, and cruel landlords. Now, it’s NIMBYs. Developers are actually on the opposite side of the NIMBYs here: they want to build. They even want to build affordable housing in many cases.

The YIMBY movement is, in a sense, the easiest neoprogressive example: it is cross-party, but slightly more center-left; it fuses concern for the poor/oppressed with hope for industry and economic growth; and it is not really easy to call extremist in some traditional sense. It’s a Progressive Era-style revolt of the pragmatic materialists. Unlike the Fair Housing Act’s concern with racism or the warrant of habitability’s concern with landlord power, YIMBYism isn’t about legislating rights into existence or dealing with something I would even call evil. YIMBYism is just contesting an entrenched interest with what it sees as a positive-sum solution. It has also been decentralized and focused largely on state legislatures.

Environment

Let’s move onto another area where building has a big part in the equation: the environment. Environmentalism was huge around the 1970s. Concerns about global overpopulation and its effect on the environment and food supply caused India to sterilize 6.2 million men in a single year.

In America, the problems of the 20th century with regards to the environment concerned pollution, air quality, and the protection of precious balancing ecosystems against an arrogant bureaucracy and a despoiling mass of factories. The environment needed protection—specifically, it needed protection from things getting built. It needed restrictions on what could be built, where, and how. It was not enough to ask the bureaucracy to do this (in part because it was deeply distrusted on the matter), so we farmed it out to individual actors and those venerable factual inquirers, the courts. Again, the solution was to create an individual right (here through NEPA),2 as well as other regulatory standards through the EPA and such. This had a lot in common with the Progressive Era push for national parks and conservation, but less in common with its push for urban beatification, including building municipal parks.

Now, the air is much cleaner and no one is building things willy-nilly—in fact, it’s very difficult to build anything at all. The irony is that what the environment needs is for us to build things—solar energy, wind energy, natural gas, carbon capture, geothermal heating, nuclear power plants. Whatever your preferred solution to climate change is, it’s going to necessitate building things. And the irony in this particular realm of policy is that one of the solutions to the old problems (NEPA and environmental review) is holding back the new solutions.

The problems of the neoabolitionists required restraint, the legislation of initial rights that could be policed by the courts, and the promulgation of regulations. The problems of the neoprogressives require scientific exploration, state-aided industrial production, and economic advancement.

For a look at how this difference is playing out socially within the environmentalist movement, see, for instance, Jerusalem Demsas’s reporting on the split in the environmental movement.

A by-the-by: if you’d like to know whether an environmental group is more concerned with conservation or climate change, an easy proxy to look for is their position on the permitting reform bill that Joe Manchin and Co. were trying to pass towards the end of the previous Congress.3

Government Structure

This is a good transition to talk about our defining issues in government structure. In the 1960s, the concerns of the neoabolitionists were an overbearing bureacracy, cozy parties with little political daylight between them, and new claims about the legitimacy of the party system. The Port Huron statement by the Students for a Democratic Society, an important document in the 1960s student movements, voiced many of these complaints. It complained that the Democratic Party was not responsive to voters and that voters didn’t have a true political choice because the two parties were so similar, so close in policy. It called, for instance, for the Democratic Party to take a stand on civil rights in the South. The 1968 Democratic National Convention was protested on many of these grounds.

The dominating government bureaucracy, expanded greatly under the New Deal and then massively during World War II and never quite scaled back, was stifling economic progress and doing stupid things like bisecting poor urban neighborhoods.

Smoky back rooms and pork-barrel legislation also became targets of suspicion. Many reforms of the legislative process in the 1970s and afterwards attempted to deal with these problems. C-SPAN for transparency and the line-item veto (struck down as unconstitutional) for pork are two well-known examples of this line of reform. Newt Gingrich’s political project can be seen very clearly as descending from the concerns of the student activists—railing against Congressional waste, term limits to reduce quid pro quos and corruption, and telling Republicans to stop living in DC (and to stop hanging out with Democrats).4

Our problems today, I might say in short, are not that the legislature is too cozy or that parties are not responsive enough to their party members. We also do not suffer from a decisive bureaucracy.

Instead, we have a performative Congress cheating to the C-SPAN cameras at all times; almost reflexively hostile partisan politics both inside D.C. and out; and Congressional foundering leading to more and more willingness to defer to presidential power (who wants to be seen compromising on something important to ‘the other side’?). We also have political primaries, which put parties more in the hands of their partisans, but which also make it more difficult for moderate politicians to make it to the general election and feel safe in their seats doing moderate, cross-party things.

At the same time that presidents and bureaucracies are more able to decide what the law is, they are less able to put the law into practice because of a lack of state capacity—primarily, in my view, because of certain laws (like NEPA) holding back state action and an overreliance on external government consultants which has left the actual government without expertise. That reliance on consultants is itself an experiment borne of the 1970s (see here for a full argument relating to consultants from

).Some of this analysis is more tendentious than other parts—suffice it to say that it seems to me the new situation requires less cries for legitimacy and purity, and more working across differences and in weird, compromising ways.

Media Context

Of course, one reason that politics polarized and calls came for it to become closer to the voters was the media context: the advent of the television and the expansion of radio. Television especially brought the country much closer to itself—I don’t believe it is too controversial to say that it helped make civil rights a national issue.

Dealing with television was new at the time, and it made for a lot of possibilities—televised debates, C-SPAN, cable news, 24-hour news. I have a personal distaste for TV news, but in addition to that, I think it contributed to polarization. The structure of TV news is that there are only a few news channels—at first there was one, as befitted stultifying, unified 1960s and such, but that didn’t last long—which creates a few different perspectives. It is not incredibly surprising that these perspectives ended up being differentiated on a line.

The relative concentration of television news as compared to newspapers also created a powerful centralization of gatekeeping. The big national newspapers had this power before, but TV news had it in spades: fighting over who gets to say what on television made sense for a while. There was a big microphone and saying things into it got you places. This, I think, fostered a sense that what was being said was important.

Television has led to many other social changes besides, some better and some worse, but which I don’t have the pedigree to comment on. It’s old hat, though. Social media and phones are the new media context that everything else must adapt to. And now we are fighting over a dead microphone:

I don't think we're going back to a staid print society, but I do think our media-saturated lives will change as we learn to grapple with social media and what works in the new context. The biggest change, I believe (and hope) will be a depolarization: not because people’s beliefs will get less weird, but because they will get far more weird. Cable news and its concentration in a few channels allowed us to organize our political ideas around our mass political parties. Social media and its splintering of strange fandoms and sui generis, but interconnected creators all on the hunt for a niche will leave many people feeling like they are not reflected in the Democratic or Republican party: how could they be? When each individual’s political ideas are a mix of seven different Substacks, three podcasts, two newspapers, and a Twitch streamer, most of them with no relation to one another personal or professional, how could they be reflected in a party attempting to get the votes of half the country?

Combine this general trend with the possibility that people are abandoning the internet’s public squares for its back alleys and basements, and you have a strong case for depolarization, perhaps combined with extremism.

The problem of social media also requires communal decision-making in a way that television did not—sure, we needed to auction off the airwaves and such, but that can all be done with bureaucrats and lawyers. Social media, smartphones, and the internet require us to make decisions like: should kids have phones in school? Do we need to do anything about porn and kids? What should the government’s role be? What is social media for? What is a praiseworthy amount of time to spend on it? What amount of time should make you tease someone? chide them? worry about their health? Especially with regard to kids: how should parents approach these things? What guardrails do companies need to put up for children? These are cultural and social and political questions many answers to which require affirmative communal coercion.

National Security

Speaking of communal coercion, let’s talk about our primary foreign rivals: Russia in the past, China now. The Cold War represented, I don’t believe it is controversial to say, an ideological fight between communism and capitalism. Especially initially. These were models of the future, and the realm of ideas and moral justification was important (even if that justification sometimes came down to “look at our grocery stores”—which, to be fair, is an important justification).

In the 1960s, the spectre of military influence on politics came into the fore with Eisenhower’s “military-industrial complex.” The national security state—including the military, but also the FBI and CIA—was powerful and entrenched.

We are in a very different situation now. For all the discussion of the liberal world order, the competition with China is less about ideological poles of History and more about competence and simple power. The Cold War was wrapped up in power as well, but the ideological cloak was important. Now, we have the general sense that China is authoritarian and centralized, which is true, but it’s not really founded on a grand historical theory so much as a grand political bargain: we make you rich and your country great, and you shut up.

The problem in America is definitely not spending too much on defense or any overbearing influence of the security state. Many people feel that our intelligence agencies are not particularly competent, our defense industry has dwindled along with the rest of our manufacturing, and as you can see below our military expenditures went down and have never really gone back up.

In Vietnam, deference to the national security consensus was deadly. After Iraq and Afghanistan, Americans don’t really want to hear another national security scare story. But I expect the facts of the situation to cause more and more Americans to be concerned about China and want to do something about it (or at least prepare to). And so we will have to deal with the problems: our manufacturing is down, our intelligence services are down, and our military capacity is down. A general distrust towards national security, which has served reformers so well for so long, will not work in this case. We will likely want to compete with China and that is going to require new ideas and a new sense of what is necessary and proper.

Economic Frontiers

Speaking of manufacturing, the 1970s had two trends: the end of a long-term downward trend in energy prices and the computerization of white-collar work. This meant less room for productivity growth and new frontiers in manufacturing (“atoms”) and more room for the same in white collar work and information technology (“bits”).

But, fellas, we’re back: renewables are cheap and high-efficiency batteries are looking to change what’s possible in terms of home appliances (and warfare). AI should continue the productivity growth in white-collar work and expand it to new areas, but will (new for “bits” technology) require massive amounts of energy. The national security imperatives noted before may further increase the economic importance of manufacturing.

This will also increase the economic cost of anti-building environmental measures.

The explosion of college education and the rising importance of white-collar professional-managerial work were major political, social, and economic facts of the neoabolitionist era. These are likely to change in some way—perhaps due to AI-related productivity and cognitive aids—and the concomitant social force of such ‘knowledge workers’ may be rebalanced in favor of engineers and some other such groups I can't imagine now.

The economic problems of the 1970s (overburdened bureaucratically-directed economy) are different than our own (deindustrialized, overfinancialized, inequality not clearly making for average material betterment). There are also new opportunities for economic direction with new technologies for dealing with large quantities of information (AI).

Racial Disparities

The neoabolitionists were fighting against formalized legal inequality and discrimination, and fought for formalized legal equality and antidiscrimination laws. The impulse was to nationalize the issue, and get northerners interested enough in what was going on in the South to do something about it. The laws were also pretty clear: no more racial discrimination. Implementation was a beast, as always (see: school desegregation), but the actual political fight was about these clear laws.

Now, racial disparities deal come from a complex of possible causes: implicit discrimination, remaining difficult-to-root-out explicit discrimination, lack of investment in certain areas, generally decreased social mobility, crime and the criminal justice system, and I’m sure others. I expect this to result in relatively more focus on economic issues and experimentation regarding social-economic causes of poverty.

Neoprogressives on the Horizon

“We must learn . . . to trust our democracy, giant-like and threatening as it may appear in its uncouth strength and untried applications.” —Jane Addams

Distrust is in the air, and cynicism in the ground. Much of their force is directed at our democracy and the society which has its survival as its charge. Benjamin Franklin’s “if you can keep it” weighs heavily these days. And so we scramble to grab whatever and whoever is in our reach, to bring whatever and whoever we can under our direct authority or that of our ‘team.’ We are panicked by the thought of total annihilation or tantalized by a vision of total victory, each just edging out of reach. The smell just before the street gets blanketed with rain: something has to give. And we don’t want to be caught out.

I should note that my whole theory is fundamentally conditional on a continuation of generally democratic politics in America as we have seen it in its various forms—not always tidy and within-the-bounds-of-play, but with a general faith in the people’s vote as the source of legitimacy and a fundamental dispersion of power across our wide plains, high mountains, grand forests, and long shores.

You might think, fifty years into these old battle lines, we would be have a more constrained vision. But we do not. I believe it is these new problems,5 pressing up from the dim dark firmament of political instinct, that have caused our present political pathologies.

I do believe pathology is the correct, almost clinically so, word. As I have said before, my rough understanding of a pathology is a habit that no longer works. The political habits we have learned over the last fifty years are not working for these new sets of problems, and so we founder.

The reformist project of the latter half of the 20th century rhymes in many ways with the abolitionist movement of the 19th century. It had its share of legislation, but it was fundamentally a parapolitical movement. In all of its primary faces, it gained and used its influence outside of the political system in order to pressure that system. Rather than localizing problems and gradually experimenting with legislative solutions, it brought issues to national attention and fought for allocations of judicial rights, often restricting legislative and bureaucratic possibilities. This is not to say that the movement was not strategic or canny or impressive—but the methods it used were distinct. And so you get George Floyd protests unprepared for the need for sustained, experimental, material political objectives.

For all the talk of Trump and his New Right, Trump himself is less something new than a pathological expression of the old guard: a businessman in politics; the decider; lower taxes and distrust for the administrative state. In his second term, he has tried more intentionally to play-act McKinley, but the effect has largely been bluster and chaos. Yes, there are new things here—tariffs, blatant financial corruption, the rhetoric, the obviously unconstitutional executive orders. But even some of this has more in common with Nixon at the dawn of our current preoccupations than any other presidential idea. But he’s not building anything—he’s a wrecking ball aimed at many the things the Republican base has been griping about for years with a few else besides: the freeloading Europeans, the unelected bureaucrats, the mooching free-traders, the libs. Musk’s DOGE is so far the old criticism of the bloated, liberal bureaucracy (we may have almost got something new with Ramaswamy) not noticing that the federal government’s bureaucracy isn’t bloated—it’s getting scammed by consultants, trudging along with 500 tons of process on its back, and creating rules that Congress has punted responsibility for thinking out.

Biden the same. He wanted to play-act FDR, but he didn’t control the party and its groups: he didn’t have the mandate. With some noises of industrial policy, it was the same big-spend giveaways (look at the dollar signs and not the construction signs, though with some more successful programs), coddling public servants and interest groups, party indecision, and muddling through hoping to get votes from moral shame.

Just look at their ages—this is your new-thinking president? The 80 year old blowhard? The 82 year old bumbler? I agree that they have sparked changes—but the change is not in them, but in the people just starting to enter the arena. There are glimmers—institutions of the New Right (some of them not even particularly fascist) trying to think through a new, national conservatism concerned with national strength and the levers government can use to form a responsible, collective citizenry; institutions of the Abundance Liberals (some of them not even particularly neoliberal) trying to think through a new, industrialized liberalism concerned with making things for people to live in and ensuring not just governmental existence, but governmental efficacy.

Many of our political paroxysms come from the desparation of the old playbook: we want a big old microphone to take from our enemies and blare into the public; we want to get legitimacy from parapolitical protest against a discredited paternalism for clean, sexy rights to legislate in a bold moral move; we want each election to provide a clear win for one of two coherent projects, big political teams that sweep into power and set the country in a direction for two to four years. The microphone is dead and the public has splintered; we used up all the magic in calling people racist and new gains in welfare are going to have to come from complex, small-bore experiments; parties are struggling to hold themselves in one piece and elections are 50/50. This is not working particularly well.

For example, is this what it looks like to see a political strategy in retreat?

Now, if you’re an impatient, megalomaniacal coward with a clinically deficient sense of foresight, you can try a coup—no, I’m not talking about your favored political nemesis: I’m talking about you.

I would not. I counsel patience and faith.

The primary reason I counsel these things is because I don’t believe I’m that much smarter than everyone else. Maybe a little bit, sure, but not so much that people will never figure out I’m right. I kid, I kid. But not entirely. It is true that much of my hope comes from the very plain belief that I am not all that. There is a deep hubris in all this control—the absolute confidence that you’re the one that has it all right and no one else can figure it out because of forces you can’t control (because you’re too darn committed to the rules). It is there behind everything from the fantasizing about a civil war to all the Overton Window crap. On the Overton Window: what you’re telling me is that you not only know what is right, but you also can’t rely on simple persuasion to get people to understand, but you also also know how to calibrate how extreme you have to go to pull everyone just far enough in your direction? Sure, bud. I’ll stick to saying what I believe.6

Dishonesty in political communication is often the result of contemptuous, egotistical distrust. I will not say it better than that same Progressive reformer I quoted above, so I will simply quote her again: “[t]he loss of authority and distrust of the people is the fatal weakness of many systems of reform and well-intentioned projects of benevolence.” Jane Addams had faith.

I do think my theory is a hopeful one, but not idealist. Certain priorities will be forgotten, or placed on the back-burner. Certain perspectives and intuitions will be left to the side. For one, it’s possible that the new censoriousness is here to stay, to some extent or another, on some level or another. This would be deeply distasteful to me. My theory could mean more injustice and inefficiency in legislation and more national splintering, both politically and culturally. A nation without a mainstream is a strange, somewhat sad idea. If religion becomes popular in a new wave, there are all the worries attendant to its irrationalisms.

From a purely tactical standpoint, I will make the note that negative partisanship, negative polarization, and anti-incumbency makes locating your movement within one party or politician a bad strategic move to the extent it is not absolutely necessary. When people care about problems, they eventually hit on a way of doing it. This theory is my rough prediction of how we will hit on doing it, through an analogy to history: nonpartisan issue movements, splintering coalitions, distributed experimentation, and legislative compromise. Don’t worry, there will still be protests and parties and ideology and tribes, I’m sure. But much will be different.

None of this is set in stone and you never simply go backwards—it is always a new age. But I think there is something to learn about the legislative, experimental reformers of the past. It can sometimes feel, when the old ways don’t work, that there are no ways that will work. The past can be a place to find possibilities for the future. It might take some time, but I believe that is the direction in which we are headed.

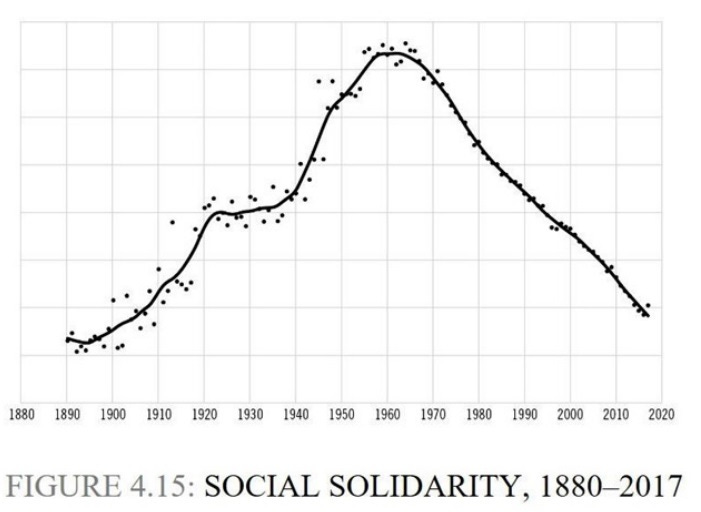

I may return to this thesis later. I have a lovely stack of books about the Progressive Era that I want to read and make a series out of. I expect this, if it does happen, to take at least three to six months—there’s a lot I want to do before that. I’ll end with a graph:

I think that the desire to tar anyone who is no maximally in one direction on all of these issues as transphobic is a holdover from the gay rights movement, where “maximally in one direction” was just a fine place to be due to the binary nature of the rights in question.

NEPA actually didn’t create an individual right explicitly, but courts interpreted it to do so, and that is really what gave it a lot of its teeth. One could interpret this as a sort of power grab by the courts against the bureaucracy, to which Congress acquiesced.

It’s an easy proxy because it made permitting for all sorts of power projects easier (i.e. was bad for conservation) but in all projections it netted out to considerably less CO2 emissions over time (because replacing old energy sources with new projects means cleaner energy).

A very underrated development, in my opinion.

I was going to add some more sections, but this post was already getting absurdly long. Here is a sense of them:

Social ties (repression v. isolation): new models of internet-physical hybrid communities in the Rationalists, a Chicago criminal justice research volunteer network, young people being interested in religion again.

Political power (voting rights v. money in politics): renewal of interest in antitrust, Citizens United v. FEC, related to the anti-bigness ideology of Brandeis and many Progressives)

Immigration (racist quota laws v. uncontrolled borders): see FdB on immigration and a lack of connecting morality to action/pragmatism reflective of an parapolitical moralizing that worked for a while, but not anymore.

I think some of these analyses are more tendentious than others, but I also think that there is a real general shape to the changing trends. And hopefully, that shape was defined well enough by these posts that some exercises can be left to the reader.

I also was going to note that the progressive era occurred after the buildout of a capital-intensive economically and socially transformative technology—railroads. I would analogize this to the internet. For a sense of how socially transformative railroads were: railroads are why we have time zones.