American Radical Reformism, ca. 1830-1970

Returning to the Neoprogressivism Thesis with a stylized history

This post is part of a three-part series. Part one is here and part three is here. Part one outlined an overarching theory of the direction of contemporary politics through a historical analogy to the beginning of the Progressive Era.

Oh, how calls the siren of numbers going up. Who can resist it?1 Sex and politics: the mind-killers. Sure, the post is centered on a somewhat-obscure historical analogy. Nonetheless it is a politics post on Substack generally in that genre of amateur woke-focused cultural sociology. I’d say I have three more posts like it until I become irretrievably a hack. But, no, it’s fine. It’s hopefully a take with little enough use in the culture scuffles that my honor as an orthogonal poster remains intact.

Perhaps this theory’s fundamentally hopeful conclusions set me at odds with the exigencies of the time, and bring it enough out of the moment to retain something beyond what is merely new or news.

Look, it is difficult to stay away. This was exciting: for the first time, someone (by no fault of their own) misinterpreted something I wrote! Online! Publicly! Because I did not spell out my ideas fully! This is exciting, as a young amateur blogger. I slinged (slung? slew?) a take! Take-slinger here! Very fresh. Very new. Very fun.

Last post argued for the existence of a distinction between progressive and abolitionist strains of American reformism, and asserted that we are heading—perhaps slowly, perhaps haltingly—towards a period of progressive rather than abolitionist dominance in American reformism. These traditions are distinguished by method and focus. In this post, I’m going to make the historical analogy clearer, telling a story about why abolitionism took hold in the center of the 19th century, how it lost its sway, and how it contrasts with the situation and focus of the progressives. In the final post on this subject, I will engage in some more quasi-Panglossian historical analysis. The idea will be to distinguish our moment and the problems by which we choose to define it from that of the neoabolitionists.

“The greatness of America lies not in being more enlightened than any other nation, but rather in her ability to repair her faults.”

— Alexis de Tocqueville, Democracy in America.

Both the abolitionist and progressive strains of American tradition are reformist at their core: they seek, literally, to re-form American society. Both are aggressive, radical movements which seek to change the nature of the life in the country. But they are different in important ways. First, we need a clearer idea of the previous set of movements and their relationship.

The Abolitionists

We must initially make a distinction between the abolitionists and the antislavery. There were antislavery politicians and groups from the moment the US was founded, even beforehand. Some of these groups even called for the abolition of slavery—but for our purposes here, these were not abolitionists. Abolitionism was a particular movement in America in the 19th century, never particularly popular but with a fervent following centered in a few northeastern cities. It never gained widespread political support, and even leading up to the Civil War it was not generally well-liked, even in the North, even in New England. Even in Boston! Even so, through its boisterous, moralizing attacks on a senescent slave society, it forced great change.

I will admit that the caption above is something of an exaggeration. But it is not farcical.

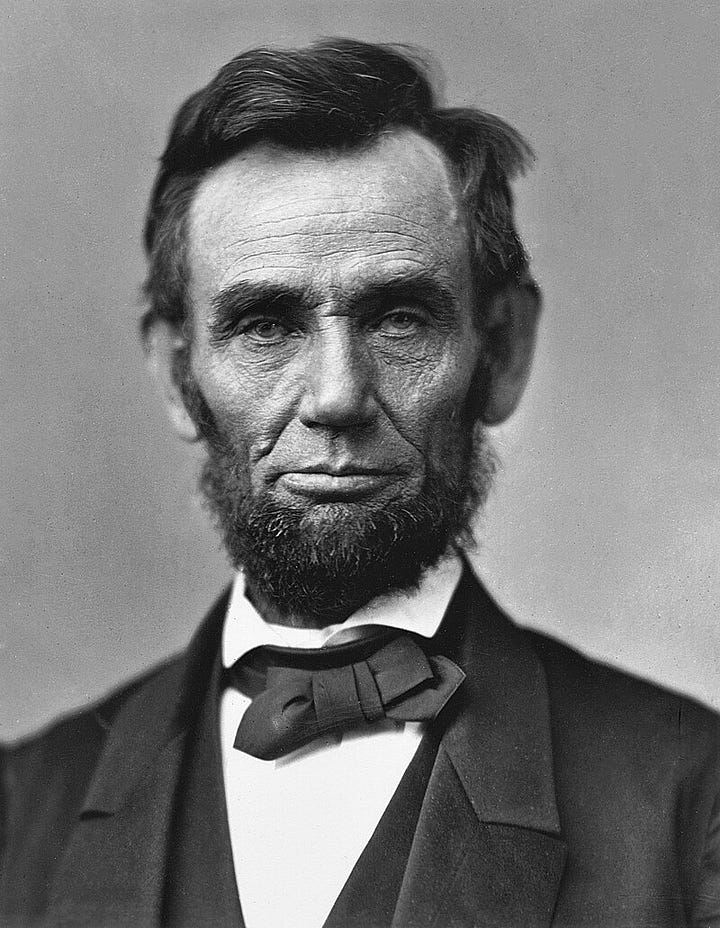

Abraham Lincoln was part of the political movement against slavery, a movement that, as I note above, existed in some form from at least the nation’s founding. Several Northern states abolished slavery soon after the War of Independence, as they had not been able to before. This antislavery movement had connections to the 19th century abolitionists, but they were not the same. The antislavery movement was political, and wanted to work within the realm of politics. Abraham Lincoln ran for President on not expanding slavery to new states, not abolishing it from where it had already taken root. He did engage in some constitutional hardball by, for instance, signalling he would not follow the Dred Scott decision. However, his justification was that he would do so within the realm of political change (e.g., legislation, executive administration, electoral politics). It was only after the North entered a war to force the South back into the Union and saw sons and brothers continue to die on the field of battle that the North expanded its war aims to include emancipation.

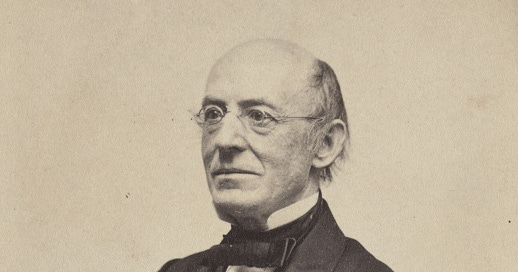

William Lloyd Garrison (left) was an abolitionist. His abolitionist newspaper was emblazoned with the motto “The United States Constitution is a covenant with death and an agreement with hell.” He often burned copies of the document at his public appearances. When a fellow abolitionist (and former slaveowner) suggested to Garrison that abolitionists should vote for antislavery politicians, Garrison denied the argument: “Political reformation is to be effected solely by a change in the moral vision of the people;—not by attempting to prove, that it is the duty of every abolitionist to be a voter, but that it is the duty of every voter to be an abolitionist.”

I could continue about the distinctions between the two related movements. Antislavery politicians were still generally unionists while abolitionists preached “if thy right [meaning southerly] hand offend thee, cut it off.” Antislavery supporters were mealy-mouthed and more concerned with keeping the slaveowners in the Union than changing things. Abolitionists were more concerned about the moral stain of slavery on the country, slaveowners, and themselves by association than they were about the welfare of the slaves. Most individuals in either movement never particularly liked the idea of black people being near them, but were furious at the sight of Southern slave-catchers in their towns and the general crime of slavery on their Christian country.

The important functional difference between the two movements is that antislavery was fundamentally a political movement while abolitionism was a parapolitical movement. Antislavery attempted to work within the bounds of politics and achieve legitimate success that way—corral votes, pass bills, compromise and quid pro quo your way to freedom. Abolitionism interfaced with politics, but the core of the movement was always outside of the political process—speeches, protests, and denunciations. One movement brought the Missouri Compromise and the other Harpers Ferry.

These differences were moral choices with moral intuitions behind them, but they were also strategic choices with strategic reasons in their favor. And in the latter sense, the abolitionist plan had an extraordinarily persuasive piece of evidence: the history to date of the United States. As William Lloyd Garrison once pointed out: “The experience of two centuries [has] shown, . . . gradualism in theory, is perpetuity in practice.” 200 years of statutes and negotiations and still there were men in chains. Instead of cajoling and compromising, the abolitionists aimed to turn up the heat—bring the issue to a head. They gained their legitimacy not through politics and political compromise but precisely because their lack of collaboration with the political system allowed them to have the sort of moral purity necessary to make the nation boil over.

The very dynamics of slavery make political solutions in America’s regionalist, semi-democratic insitutions difficult. Not only is the principal party affected unable to make a showing of its interests, but the existence of the oppressed increases the political and economic power of the oppressors. Economically, the cotton gin made the south and its planter class. Politically, every slave gave the South three-fifths of a census point towards the House of Representatives and in choosing the president. The normal democratic politics of voting blocs, representational leaders, and interest groups don’t really work for this problem: you don’t get the slaves’ votes for vouching for them and the worse the problem gets the less relative political power you have. The initial hope was that slavery would die off (at least, this was the hope of the many of the tidewater elites at the Constitutional Convention), but things didn’t go that way. And nothing was working.

War is politics by other means. And the abolitionists eventually ended up with war because politics wasn’t working. But that’s not necessary for all problems, as we’ll see.

The Progressives

In the wreckage of the Civil War, the North wanted to get its money’s worth. So, Reconstruction. Then, tragically, Redemption. The popular political will of the North (which was never particularly deeply concerned with the actual welfare of black Americans) for a large-scale social remaking of the South faltered and then collapsed. Calls for reconciliation between South and North allowed the country to repair itself as a political unity. The veterans of Union and Confederate armies shook hands at the cost of stepping over the newly-freed and continuously-oppressed black men and women to do so.

The magic of American society is its ability to forget and remake itself. But in this case, that very magic showed, as it often does, its cursed obverse.

As radical, reformist Americans with political influence forgot about their black countrymen, they turned their attention to the new issues created by industrial society: working conditions, food quality, labor unrest, and social alienation. But the way these problems were solved, as I detailed in the previous post, had a very different character to that of the abolitionists. Here, reform was intensely political and piecemeal. There were Progressive factions in both parties, and the essence of Progressive politics was legislative. Workweek protections, the FDA, all the antitrust laws that are now seeing a revival—these were statutory provisions pushed through the ropy compromises fundamental American governance. If progressives contended with any parapolitical forces, it was those of consolidated corporations and activist courts pushing against them.

The difference is not that no one was paying attention to the economy during the time of the abolitionists, or that people weren't having new ideas on all sorts of things, or that politics was not chugging along. But the focus specifically of radical reform was very different in each era, with different problems and different strategies for solving them.

The Progressive Era was not a time of moral purity and revolutionary clarity in the reformist classes, but one of popular broad-based engagement and radical local experimentation.

This is also not to say that the only strategy was legislative or that the progressive movement was not radical or moralizing. Antitrust and anticorruption initiatives, for instance, were both radical and morally framed. The whole movement was still about moral and material reformation. The difference was the method, and that method reflected the problems of the day and was reflected in the character of the movement.

Workers outnumber bosses. Bosses (especially big bosses) are national and workers are local. Businesses stretch across counties and states, but people live and work, generally, in the same one. Workers have less education, political connections, and money than bosses. But businesses don’t vote, and workers do. When you are talking about material reforms that benefit workers, these are not just facts about the injustice of it all, but about the political economy you are working with. And they all point towards local government, picayune interests, and legislative influence through the vote and mass organizations.

The brute facts and complexity of economic problems require a willingness to experiment (what is a reasonable workweek? Can meatpacking plants run with these regulations? How do you get compliance with standards?) and promote gradualism (a 3% tax? What about a 4% tax? 5%?). You can find numbers in the middle. You can trade money you don’t care about for money you do. Less so with questions of fundamental rights, like whether there can be slaves. This is the difference between analog and digital issues.

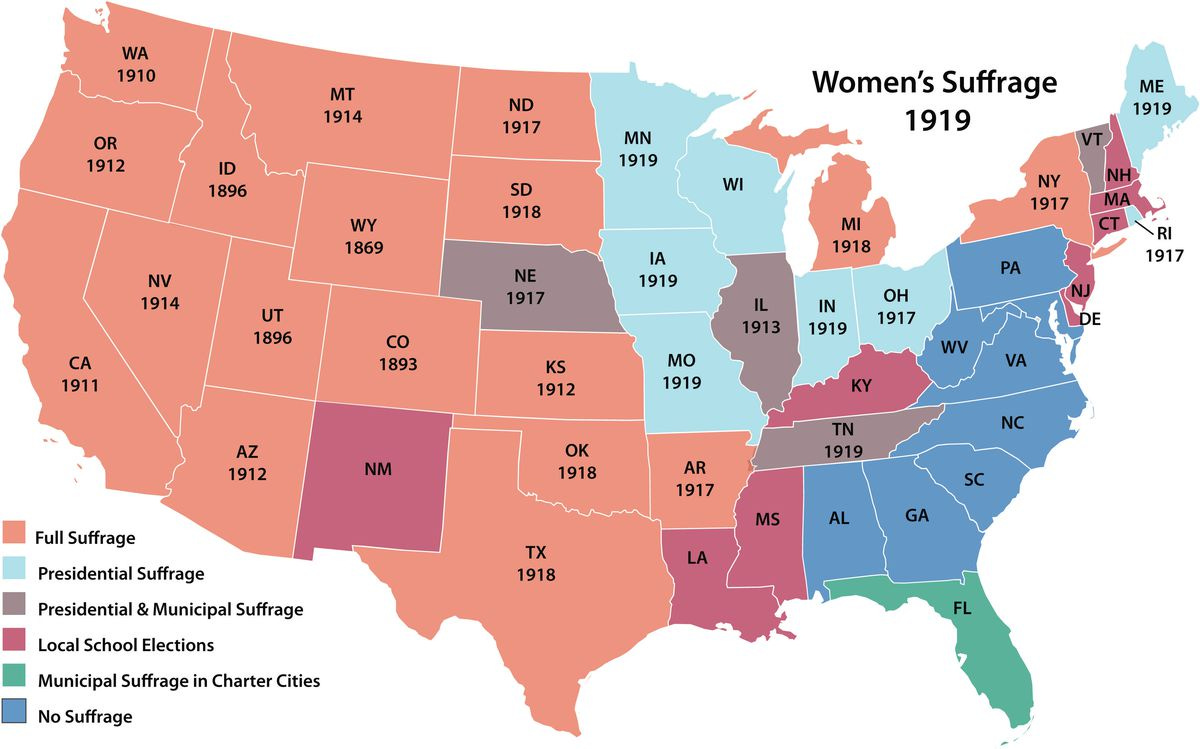

Take the hardest case for this paradigm: women’s suffrage and the temperance movement. These are radical, moralizing movements concerned with a class of people that historically were not formally part of the political process. It also seems like a digital issue—you can either vote or you can’t. Yet instead of a nationalizing, parapolitical strategy, turning up the heat on the question of voting, the sufregette movements were highly political, compromising, and gradualist, which led to maps like this:

One thing to note is that while women could not vote, they generally outnumbered the men, and most men and women have at least one person of the other group with whom their social connections are, ahem, intimate. That allows for local, political power much more than the also-unable-to-vote slave population pre-Civil War.

The End of the Progressives

The experimentalist and government-directed project of the progressives reached its zenith with the New Deal and World War II rationing. The failures of unregulated markets was shown conclusively by the Great Depression, and government programs to set bounds to and direct the market exploded in the New Deal. The government regulated the price of wheat, brought industry players in to set standard practices, and set itself up to mediate labor disputes. During World War II, the government ran the economy as much as any other actor, rationing everything from boots to airplanes. Statutory and regulatory supremacy reached its zenith as well, with FDR cowing the Supreme Court and massive amounts of federal legislation being signed into law.

Which brings us to Robert Moses. The Progressive movement’s ethos of communal legislative decisionmaking, experimental regulation, and social engineering congealed into a government-directed, bureaucracy-enforced repressive society. No individual epitomized this lattermost face of Progressivism than Robert Moses:

The utter lack of respect for complexity that Moses’s worldview evinces, its complete certainty in its understanding of all relevant factors, and its lack of even the most basic economic ideas of supply and demand and incentives (Moses believed he would improve the urban housing situation by destroying poor quality housing and increasing minimum standards of suburban housing): these are all bad.

They are also understandable: once you have experienced the New Deal and WWII, why wouldn’t the government be able to cleave a neighborhood in two? Why wouldn’t it decide how much airline tickets can cost? Why wouldn’t it build a dam wherever it thought would serve the public interest?

The Progressive project was not only losing credibility economically, but morally. The detente on race relations and segregation, reminiscent of the post-Revolution gag order on the slave trade, was a major ground for critique of the old by the new. It began to break down in the 1940s and 1950s with the NAACP’s challenges of Plessy and “separate but equal.” Brown v. Board, its eventual enforcement by the executive and legislative branches during the Kennedy administration, and the 1960s Civil Rights movement declared race as a new front of American societal struggles. The advent of contraception, the pill, and new sexual mores discredited the old, restrictive norms of gender relations. Environmentalist concerns did not fit well in the old model of industrialist-worker political contests. The gay rights movement similarly was out of place in the time of communal responsibility, sexual restraint, and general prudishness. The Vietnam War certainly did not help the credibility of those in power and their professed ethic of deference and good order.

This is the context in which the neoabolitionists begin to move.

The question is not whether there is reformism or moralism or radicalism. This is, after all, America: that aggrandized, discontented, grasping land. The question is where it is located, where it is directed, and how it will proceed.2

In the third post, I’ll bring this theory from the end of the Progressives to our present moment.

For some reason my early Immanuel Kant post, from an earlier abortive attempt to start this blog, has double the views of all other posts barring “Moral Masturbation” and “Do Not Call them Progressives.” Are people this hungry for the Kant-explainers?

I’d like to imagine that each of its views comes from a desperate freshman phi-curious college student panicking because they don’t understand the Groundwork. I like to imagine them scrambling for any possible online page that could help them with their imminent paper, only to find my sorry attempt to start a series I never returned to. Someday, once I’ve either given up on or finished my other technically-current series, I’ll return to Kant. Apparently there’s views in them there philosophers.

To get even more granular with the historical metaphor, one could look for parallels between the populism of the 1890s and the right-wing populism which first re-emerged with the Tea Party Movement but really gained influence in the Republican Party with Donald Trump’s rise. One could see our contemporary moment as a sort of neo-Redemption after a Long Reconstruction beginning with the legal movement for equal rights in the 1950s and 1960s. But, of course, at this point we are much more in the thick of it, and have much less perspective about what facts are important and what are not. These theories are far less the railroads of history than the paths of it—some more well-trod than others, but none requiring much more than a few important, concerted decisions and fortuities to become our chosen trail.