This post is the first in a three-part series. Part two is here and part three is here.

I’m not proud of doing political commentary right now. This blog, as it stands, is almost allergic to topicality—monthly post schedules tend to do that. And I don’t plan on changing that anytime soon. Too many bloggers circle around the same wells, dredging up old water for new currents. I want, so far as I am able, for each post or series thereof on this blog to be a mystery; I want this blog to be inscrutable except as an expression of the cacophony inherent to any individual and my deep personal sickness of the word. I will, of course, not be successful in this endeavor. My thoughts, regrettably, to some extent hang together. I will draw on old thoughts to raise up new ones and relitigate previous arguments when there is new reason to. Nonetheless, I hope that the political commentary I do here is cranky, obscure, and untimely enough that it remains worth being said by me.

By 1908, the economic reform platform of the Progressive Movement in the United States had butted up against one of the great achievements of 19th-century American politics: the 14th Amendment. That liberatory constitutional provision making citizens out of slaves and protecting the rights of all was stymying the ability of states to protect workers. The Supreme Court found in Lochner v. New York that such reforms violated the Due Process clause of the 14th Amendment.

The general argument had five steps. First, the text of the amendment:

No State shall make or enforce any law which shall abridge the privileges or immunities of citizens of the United States; nor shall any State deprive any person of life, liberty, or property, without due process of law; nor deny to any person within its jurisdiction the equal protection of the laws.

Second, the due process protection includes substantive due process—i.e. substantive rights which are necessary to the fulfillment of due process.1

Third, this substantive due process included a right to contract freely under the “liberty” provision.

Fourth, this right to liberty is subject to “reasonable restraint” by a State through its “police power for the protection of health, safety, morals, and the general welfare.”

Fifth, this police power must be used as a means to an “appropriate and legitimate” end.

In applying this argument to the case in Lochner, the Court found that setting maximum working hours for bakers had no legitimate end in general welfare or otherwise and that therefore the state could not pass such a law which obviously was only intended to help a certain group at the expense of others.2

Three years later, Muller v. Oregon had finished winding its way through the court system, ending up in front of the US Supreme Court. Muller v. Oregon concerned the constitutionality of an Oregon law instituting a forty hour maximum workweek for women. The same argument as for Lochner would apply (modern sex and gender equality laws were not an issue) and Progressives were concerned that this legislative protection for workers would also be struck down.

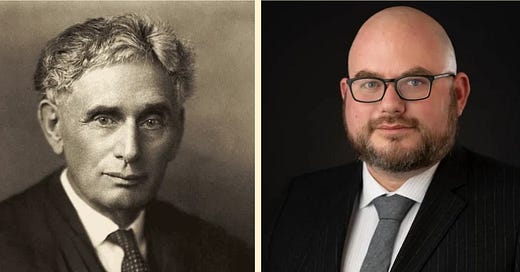

The question was how to establish a reasonable basis for this use of a state’s police power. Enter the Brandeis Brief. Noted Progressive lawyer and future Supreme Court Justice Louis Brandeis submitted a 113-page brief, of which only two were legal argument (basically spelling out what I outlined above, with the additional note that the Court may take into account facts of common knowledge). The other 111 pages consisted of two parts. Fifteen detailed the prevalence of similar statutes in America and elsewhere. Eighty-four consisted in a slew of whatever possible statistics, research, and expert opinions could be found attesting to the frailty, weakness, and inferiority of female workers; the need for their special protection; and how important it was that they had enough time to be at home raising children and doing domestic labor. It was a slurry of 19th-century scientific sexism, which we have good reason to think Brandeis mostly disbelieved, but that he nonetheless presented to the Court in an attempt to show that at least enough information was around such that a state had a reasonable basis and end for its law—it did not have to be right, just reasonable.

The Brandeis Brief is known now for its novel use of empirical data in legal briefing, but I want to focus on its realpolitik. Brandeis compiled his brief with the help of Josephine Clara Goldmark, his sister-in-law and a fellow legal reformer. These were prominent members of the Progressive Movement, which had many fellow-travellers in the temperance movement (which was largely led by women) and was generally strongly in support of women’s suffrage. The entire structure of their argument (and, indeed, the law which precipitated it) was deeply sexist. But hey, Muller v. Oregon came down on Oregon’s side, the law was upheld, and the same Progressives that cajoled the Oregon state legislature to pass a bill holding women to a forty hour workweek went back later and tried to get a bill holding another group to a forty hour workweek. And more and more such bills were passed, and each time, a few more workers were protected by a forty hour workweek—a different group of workers or a different state, it didn’t matter: whatever you could get the votes for. Until everyone had a forty hour workweek.

So here’s my question: what political faction in modern-day America would submit a Brandeis Brief?

Our Modern ‘Progressives’

I’ll answer that question in the affirmative shortly, but for now, let me do so in the negative: the lefty groups that dominate the definition of “progressivism” today would certainly not. The groups I’m referring to are those generally called some version of woke, social justice activists, cancel culture, the intersectional left, the Groups, cultural Marxists, or leftists. Also progressives. These groups would have their reasons for not submitting such a brief: coalitional unity; the cultural effect of arguing for protection using sexist standards; the possibility of such a precedent creating issues for women’s rights far down the line; the basic moral capitulation of using such rhetoric; the danger of platforming/dignifying such ideas; the necessary interlocking of feminist and labor ideals. I’m sure the list could go on. The point is not whether such calculations are correct, but that this theory of change is simply not the one evinced by the political tradition of the American Progressive Movement.

The Progressive Movement of the early 20th century was built, if anything, around the opposite theory. They employed a ‘wedge’ tactic, where they would try to get their foot in the door by any means possible, lobbying for incremental improvements in every area they could when the opportunity arose. You ask for however much you can get and then you come back later. The game of democracy keeps going, and (as long as you’re playing within the game) tends to punish movements that attempt to shoot the moon. At least so is their theory. You ally with whoever will vote for your bill and the strangeness of your bedfellows is, if anything, an opportunity to make whatever change you get more durable. The Progressive Movement was cross-party—there were Progressive Democrats and Progressive Republicans (Teddy Roosevelt and Woodrow Wilson were both Progressives).

There are some analogies here between the Progressive Movement and the early Civil Rights movement, which is where contemporary social justice activists find their roots—the NAACP’s incremental legal fights, for instance. However, there are far more discrepancies. The Civil Rights movement was, by necessity of political economy, nationally-focused and largely non-legislative (especially with respect to the courts). The Civil Rights movement had a few foundational pieces of federal legislation and a huge project of legal activism. This is mirrored in the experiences of the environmentalist movement with NEPA and subsequent legislation; various feminist moments with big SCOTUS decisions and a couple of foundational federal antidiscrimination laws; to some extent with the gay rights movement culminating in Obergefell; and eventually with Ross Perot’s Ralph Nader's3 consumer protection activism. Contrast this with the Progressive Movement’s anti-judicial political economy and focus on state-by-state experimentation and incremental legislation. There are a few big, national, Progressive Movement pieces of legislation (the antitrust acts, the attempt at Prohibition, women’s suffrage), but most of the Progressive Movement wins are small-bore statutes on the state level. No more child labor here, forty hour workweeks for a group there, better industry workplace safety guidelines in a third place.

The earlier mention of Woodrow Wilson brings up another incredibly important distinction between the Progressives and modern lefty political forces: racial politics. The Progressive Movement was laser-focused on economics, notoriously ditching racial concerns basically whole cloth. Progressive crusades included those against (largely ethnic/immigrant)4 corrupt political machines in cities which created massive patronage networks and social services for local newcomers. Woodrow Wilson, the president who showed The Birth of a Nation in the White House, was a Progressive President. The movement had nothing to say or do about Jim Crow laws. Contrast this with ‘progressive’ nowadays almost being a byword for DEI programs, radical5 cultural and political critiques, concerns over racial disparities, and a focus on racial slights and oppressions.

Our Modern Progressives

Who would submit a Brandeis brief? Matt Yglesias would. In fact, I think he kind of already did (although both less offensive and sadly less impactful than the original). Yglesias has explained before that his inspiration in writing One Billion Americans was to give an argument for a classically liberal conclusion from a premise that would be convincing to conservatives: argue for immigration from a national security and greatness perspective.6 But it’s not just one man.

The YIMBY movement takes all comers and the New Industrialists had their bible7 come from Brad DeLong while counting the American Compass as a fellow traveler. The ‘abundance’ movement may be spearheaded by Derek Thompson and Ezra Klein (see also), but James Pethokoukis’s blog “Faster, Please!” comes from a conservative think-tanker and is fundamentally interested in the same questions. YIMBYs take every win and come back asking for more. They have a ruthlessness, or a lack of care for having the right friends or doing things in the right way—in fact, a distaste for obsessing over procedure is another part of the general vibe of the new Progressives. ‘Progress Studies’ is popping up and recently had its first convention, featuring various thinkers with different primary concerns and political traditions but all focused around the general sense that we need economic reform to rebuild the American economy. A new wave of environmentalists is trying to change the movement’s focus and tone, with one prominent voice being Sam Matey.

Also, of course, note that none of this has anything to do with racial issues except in the extremely plain way that a better economy for everyone—especially workers and the less-well-off—is a better economy especially for racial groups that tend to be worse off economically.

I try to edge away from the polemical here—no problem with polemics, but I generally write here because I’m trying to wrestle with ideas, not advocate them. This is about as close as I want to get to a polemic: these people are Progressives.

Other than those I already mentioned, here’s a few people and organizations I might consider part of this budding Progressive constellation:

Jerusalem Demsas

Tyler Cowen

Anyone who was at the Progress Studies conference

Oren Cass (maybe)

Possibly GrowSF

Greg Gianforte

I Am Not a Linguistic Prescriptivist

So why did I write this?

In part because I am a bit of a pedant, sure, but moreso because I think this linguistic distinction is a hook for a real and useful mode of analysis of contemporary American politics. In short: the neoabolitionists are dying and the neoprogressives are coming to take their place as the main reforming force of American politics.

I think it is useful to distinguish two (of the many) traditions of American politics. One is abolitionism, with its radical idealist focus on the promise of this country as a land of free equals, unoppressed by the old hatreds. It often draws on America’s religious, especially Protestant, tradition of moralism and revolutionary ideals and demands justice. It has cropped up most prominently, I believe, in our Revolutionary War, the Civil War, and the Civil Rights eras. Another, separate tradition is progressivism, with its pragmatic yet fundamentally compassionate experimentation towards a materially better society, less concerned with the soul of humanity than its dwelling-place. It remains radical and confrontational, yet also experimental and incremental. It has cropped up most prominently, I believe, in the post-Constitution Founding era, the Progressive Era, and perhaps once more soon enough.8

The truth is, the name doesn’t matter. Aaron Zinger is I believe talking about the same thing that I am when he calls for a Whig Party, and I wouldn’t mind going by Whigs if necessary (though I think it is less likely that a new party rises to give voice to these ideas than if we see a movement somewhat orthogonal to and somewhat in line with the party system, and also this would be good). If I could choose, though, I would probably go with “neoprogressives,” as it would keep the original name while distinguishing itself from its colloquial use. It would also mirror and contrast neoliberalism, providing an easy distinction to the ‘neoliberal era’ we’ve decided to call our last 40 years.

With the historical analogy in hand, I think—barring any path-breaking political tumult in the next 5-10 years—we should expect an era to eventually bloom not unlike the Progressive Era. So far I have largely left to the side whether and to what extent I think this movement is good. There is a lot of hope for economic experimentation and new avenues of political participation; there could be a decrease in affective polarization, or at least an increase in the complexity and nuance of our divisions; there are concerns over racial retrenchment and decades without progress on that front. But all that is for another post, or maybe another writer entirely.

Currently, it is those on the leftward side of the political spectrum who cheer on such rights: Roe v. Wade’s right to abortion was found through substantive due process, as was Obergefell’s right to same-sex marriage and Griswold v. Connecticut’s right to contraception. The members of the Court considered most conservative are those looking to do away with substantive due process as much as they can (see Thomas’s concurrence in Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization, where he argues that perhaps all substantive due process decisions should be looked at again). This, however, was not always the case, as we can see in the example of Lochner.

As for why they found this (and why it is wrong), Justice Holmes’s dissent is persuasive:

This case is decided [by the majority] upon an economic theory which a large part of the country does not entertain. If it were a question whether I agreed with that theory, I should desire to study it further and long before making up my mind. But I do not conceive that to be my duty, because I strongly believe that my agreement or disagreement has nothing to do with the right of a majority to embody their opinions in law. ... [A] Constitution is not intended to embody a particular economic theory, whether of paternalism and the organic relation of the citizen to the state or of laissez faire. It is made for people of fundamentally differing views, and the accident of our finding certain opinions natural and familiar or novel and even shocking ought not to conclude our judgment upon the question whether statutes embodying them conflict with the Constitution of the United States.

Thank you Lee for pointing out this mistake.

In the original sense, as in getting to the root; revolutionary.

I love these sorts of perspectives. Traditions—political, religious, ethnic, or otherwise—are fundamentally cacophonous. They capture something far too primordial to fit neatly into our red and blue teams, like a tinkertoy submarine attempting to ignore the vast beasts of the deep. In comparison to the unthinking tribalry of modern politics, a tradition bears down with almost Lovecraftian contradiction. See, e.g., this book by a conservative animal rights activist whose Christian convictions lead him to militate against the cruelty of industrial agriculture.

There might be a historical analogy to be had between Concrete Economics and Georgism in the original Progressive Era.

A friend tells me that the Richard Rorty once said that divide in the American left depends on whether you get your Hegel from Dewey or Marx. If that helps you understand it—first of all, God help you—then I think it’s a quite good approximation. Louis Menand once distinguished those that take the Declaration of Independence or the Constitution to be their guiding light.

“rights movement culminating in Obergefell; and eventually with Ross Perot’s consumer protection activism.”

Don’t you own Ralph Nader here?

Very well put. I think the seemingly rapid success on gay rights made a lot of people feel like progressive change was inevitable and that tradeoffs were unnecessary. Now that we are entering a new conservative era (following rapid inflation, just like last time), perhaps people will listen and change their tactics/expectations.