Market Society [2]: What Were They Thinking?

To understand the market society, you have to think like a market society

This post is part of a series. First post here.

In the first post, I attempted to introduce an important dynamic in modern society: the power and prevalence of markets, as well as the contemporary distrust of them. Important to this discussion is the construct of the neoliberal 1980s. I find there is much lacking in that construct. This post will take it as a jumping off point to re-describe that shift and what I see as the primary justification for it.

There are no Bogeymen in History

The absolute least interesting or enlightening way to engage with the ideological trends of the past is to assume that they were in the narrow self-interest of one particular powerful group that was somehow able to provoke a mass hallucination on the part of everyone else. Rather, the ideas were almost certainly more in the interests of some groups over others (as all are), but their ability to find purchase in broad segments of the population likely relates to the felt necessities of the time, a desire for distinction from some other set of ideas, and preceding cultural shifts or heritage. All solutions create their own problems in time, but that does not mean those problems were part of some masterminded plan from the outset. Rather, it is the responsibility of those with the benefit of hindsight to see from the consequence what was inherent to the antecedent but unknown in its time. The market turn is no different.

I want to specify what I mean by the market turn. The “neoliberal bogeyman” theory of the last 50-odd years of US history is that beginning sometime around the early 1980s, the US entered a period of welfare cuts, mass deregulation, and cratering public spending that has continued to this day. This is, according to the theory, because of the neoliberals thinking that the market will trickle down riches from the top, so no need to regulate it or provide for the poor (or they are plutocrats who don’t care about the poor). There are three problems with this theory:

America has gotten more redistributive.1

The amount of regulation in the US has gone up.2

The US government’s domestic welfare spending as a share of GDP has risen.

For a fuller treatment, see here from Noah Smith, which also tackles questions of

Free trade: not a whole lot of change other than China (it’s always China when you talk about free trade);

Privatization: not a thing in the US where there was little to privatize (though you could argue the farming out of government capacity to contracted NGOs is similar and actually bad, but not usually part of the orthodox neoliberal bogeyman theory);

De-unionization: actually began in the late 1950s, in substantial part due to the state-level right-to-work laws which were enacted almost entirely in the 1940s and 1950s.

As you might be able to tell, I generally disagree with the neoliberal bogeyman theory. But I do think people are trying to describe something real when they talk about it, and I have a theory of my own.

From Crisis to Consensus

The theory of the era begins, like all such theories should, with the crisis of the preceding one. Let’s take a first run at it from The Rise and Fall of the New Deal Order, 1930-1980 via Brad DeLong:

Decay began to set in as a result of growing gaps between what the New Deal order promised its constituents… and what it actually delivered. A gap emerged first in the early 1960s in regard to the disenfranchised and poverty-stricken status of American blacks; another appeared in the moral turbulence and growing drain of international military commitments on domestic prosperity occasioned by the Vietnam War; and a third and related gap appeared in middle-class youth’s alienation from the highly organized, bureaucratized character of the New Deal order that… stifled… authenticity and individuality…. Tensions were aggravated by the often vacillating and halfhearted efforts of Democratic party elites…. Each smoldering tension would trigger a political explosion. The cumulative effects of such explosions would shatter the Democratic party as a majority party and discredit its liberal doctrines. By the mid-1970s, as a result, the New Deal political order had ceased to exist…

Before the New Deal order was in economic crisis (the 1970s), it was met with social crisis: the counterculture of the 1960s. Against the staid, organized society of their forefathers, the boomers wanted freedom and authenticity. They strained at the yoke of a communal, ordered, traditional society which promised widespread prosperity and sound, responsible leadership for the simple reason that it had, at crucial moments and in crucial ways, failed. This is, roughly, my imagined dialogue between the New Left and the Neoconservatives:

New Left: We believed in America — its principles, its mission, its values. But we grew up. America doesn’t believe in freedom — only you get to decide who speaks (and what they say). America doesn’t believe in equality — look at our black brothers in the South. America doesn’t believe in government of, by, and for the people — look at your two identical parties with no choice for us, the voters, to make. America is not some benevolent leader of the world — look at your petulant, racist coercion of these supposedly free countries. Why do you get to tell us what to do? Where do you get off telling us where to go, how to live? You want me to go work in an arms factory so the sweat off my brow can kill a child halfway around the world? So I can, what, buy myself a little box surrounded by shiny people?3 Go to Vietnam and die? Praise the only country in the world that has used nuclear weapons on human beings? For what? Why? You don’t get to tell us anything.

Neocon: You are a child. You know, I was a communist once. I was active fighting the radical fight for equality and progress before you were even born. And we were radicals, real radicals, not like you brats. You have no discipline, no idea of what change means, the hard work and gritty details that go into it. You don’t know all the ways I have seen well-intentioned government destroy people’s lives. You just see injustice, phantasms of it even, and want to start tearing things down. You think you know the answers when you haven’t even started thinking about the real questions. Just because the world is tragic does not give you a moral blank check. You may call it freedom, but I see petulance of your own, naivete, wishful thinking, and a deep intolerance.

New Left: So you would rather us… what? Sit here insulted and constrained by bureaucratic elites who are such moral cowards they won’t even do us the honor of telling us the truth? We have rights, rights that you ignore, rights that are the essence of the America you pretend to defend. You love your hard-nosed pragmatism, but when does that simply become cruelty, fear in the face of necessary and humane changes, or mean self-interest?

Neocon: You certainly do love your rights. But what about your responsibilities? A right to this, a right to that. Those rights come from others, from their concessions and from resources that could go to other purposes. And rights are nothing without their concordant responsibilities, which actually connect you with the community rather than single you out for special care.

New Left: You always talk about responsibilities, but what are they beyond a way to keep us quiet? What about your responsibilities to black Americans? To the Global South?

Neocon: What is your actual proposal? Invading the South? Having our ambassadors sit with the Russians and sing Kumbaya?

New Left: Fascist.

Neocon: Child.

The counterculture movement of the 1960s is well-known, and it is even fairly consensus history to say that the 1970s is when it was mainstreamed. But where I break with common sense is that I don’t think the 1980s were a break from the 1970s or 1960s. The neocons were the true holdouts of a previous way of thinking, which was twisted by the appearance of opponents on a side of the political spectrum they were not used to doing battle with. Most neocons began their political lives as Marxists and liberals, but reacted to the New Left and the failures of big government programs by shifting right. This battle between an old way of thinking — responsibilities, deference, hierarchy, community on the one hand and rights, authenticity, egalitarianism, and individualism on the other — ended in the 1980s, when the conservative movement capitulated. It did not capitulate on substance, but on form — the language of the day became fully that of the counterculture.

Ronald Reagan, in terms of domestic effects, mainly contributed vibes. The more important political and legal changes happened before him — Carter deregulating airlines, the previously-mentioned right to work laws — and his legislative effects were not really a large break. What he did was create a conservatism for his day. Not a conservatism of communal responsibility and Burkean “little platoons,” but of the individual, free from government malfeasance to work, pray, and make a shitload of money. Social democracy had failed its sustainability test and people didn’t trust big government — or, really, big anything. But it was not the conservatives who fired the first shot — it was the leftists.

The Birth of Market Society

The market society was born from the attempt to square these very circles. When conservatism had to reformulate itself for the post-New Left era, it could retain its historic suspicion of new initiatives, but it could not retain its insistence on communal responsibility and norms. Private (and fervent) practice of religion would be the closest it could come. Liberalism, for its part, could retain its focus on individual rights and even sympathy for the poor, but it could not retain its blindness to demographic characteristics. A focus on discrimination and intergroup equality would replace willful blindness.

Big government could not be trusted, whether due to incompetent public housing, the failures of Vietnam, inefficient regulation, highways bisecting black communities, or so on. Social norms could not be trusted, whether due to racism, secularism, sexism, perversion, fundamentalism, ‘urban crime’, or so on. In the world of the free individual, of distrust with and contention over both centralized authority and localized norms, what you can believe in is a well-regulated market where people can make their own decisions. If we could just get the markets all functioning, everyone could just pursue their own good and we’d all tick by in a clockwork utopia. The national ethic is the market, the poverty rate, and self-interest — what else can we agree on?

From this, it is a short step to the idea that a good, upstanding American is one who makes themselves some money — usually by being smart and ambitious.

This is my story of the advent of the market society. I don’t think it is a mirage, though its focus on the cultural and social rather than material and economic makes me view it with a healthy dose of skepticism. Nonetheless, I like it a lot more than others’ stories. For one, it makes the increased regulation in some areas (especially the advent of NIMBYism) parsimonious to the rising inequality and over-individualized sense of alienation. It also allows us to get out of the rut of talking about poverty rates (which have gone down) and welfare cuts (which have not really happened) and get into what I think this discussion is really about: exploitation and status.

Aside: Material Conditions

Here are some other contemporary conditions that may have made this shift seem more enticing/sensible:

Distinction from the coercive, anti-individualist Soviet Russia.

The failure of Nixon’s price controls.

The recession of the 1970s and related lack of lower energy prices. Some, such as Noah Smith believe that the lack of lower energy prices in the last 50 years has been a leading cause of lackluster growth and inequality.

Rising inequality. In particular, the importance and hotness of newly-deregulated finance and the buildout of the internet (note that the gilded age occurred around the buildout of the railroads), as well as the increasing centrality of the 4-year degree. Money and smarts got related and differences in money got increased (social status often tracks economic heft).

More nationalized community, increased internal migration, and lessened discrimination means more local pluralism and cultural options. This makes it more difficult to enforce local norms and reduces their legitimacy.

On Their Terms

Now, before we get into the contemporary complaints, it would be unfair to the people of the past to present them as mere reactionaries (in the literal sense of the word). They were not merely reacting to their surroundings and moving in the other direction. They had their own theory of the case, a theory of why a market society would finally be the one to work. As I believe that we are currently somewhere in the process of another social shift analogical to the 1960s or 1870s (probably somewhere towards its beginning), it is important to see the vision of the market society before understanding why so many people are mad at it. Much as seeing the crisis prior helped elucidate the advent of the market society, so too seeing the vision of a market society will help elucidate our current moment.

For a saeculum-defining theory, the lowest common denominator is quite low. So too is this model quite abstract and basic. Elucidations upon it, clarifications, justifications, tweaks, and compromises with reality all occurred — no one was simply stupid. But it was all done with the assumption that the following was the right model of the basic dynamic at play in society. The overarching schema was a highly complex social organism, but it was, I believe, organized around something like the following model. In keeping with the contemporary presentation of market society as a creation of the neoliberal economists, I will give my interpretation of the model which market society ran on through a peek at my travails as an undergraduate economics major.

The Economists’ Motte-and-Bailey

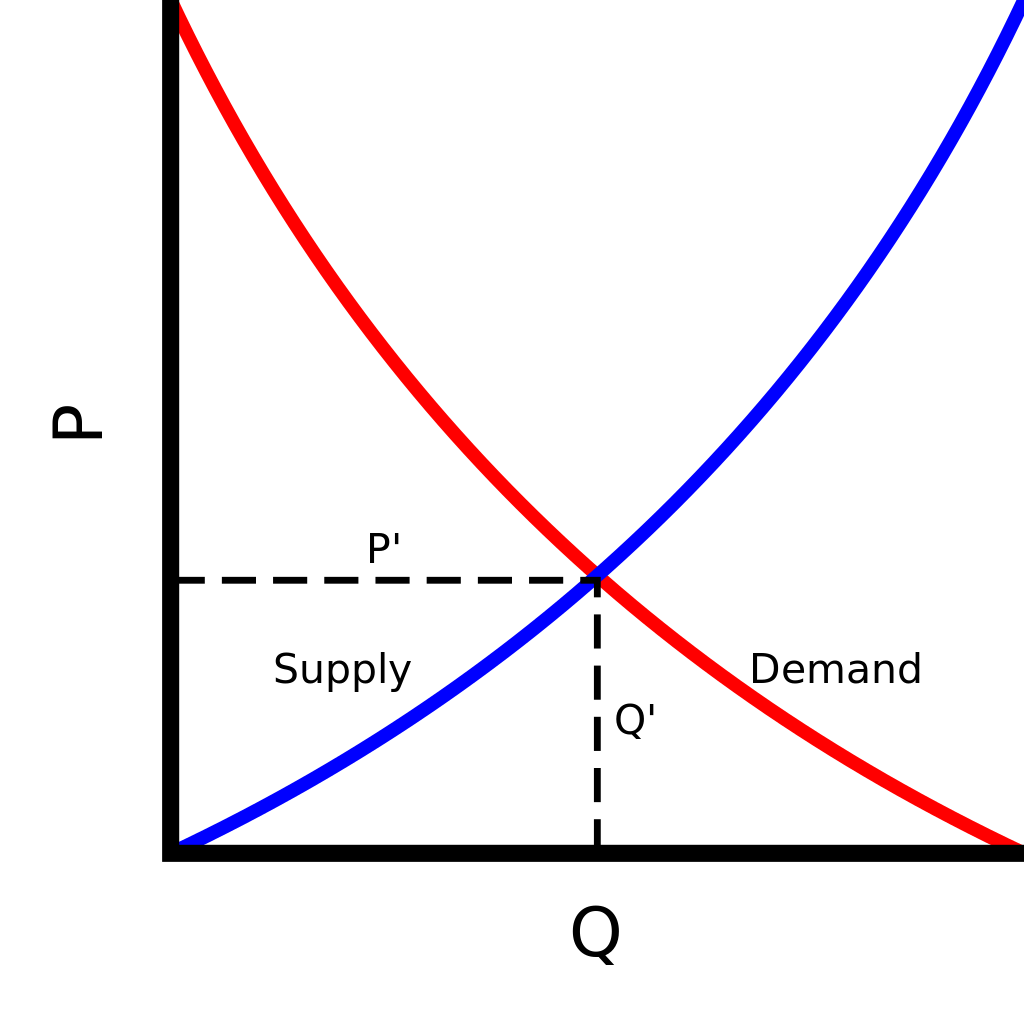

Your first economics course in university is 30% vocab and 70% having just loads of fun with this graph:

This graph is a market. Price is on the y axis and quantity on the x. For all markets, you assume that there is a distribution of how much people are willing to pay, with some people willing to pay a lot for the good, other people willing to pay less, and eventually you run out of people who will pay for it at all. Consider the market for Austrian kaiserschmarrn. There might, in the abstract, be someone who would pay upwards of $100 for some solid fluffy kaiserschmarrn, if they couldn’t get it anywhere else.4 Most people, though, would not pay that much for kaiserschmarrn, and you can’t run a restaurant selling one order of kaiserschmarrn once every 3 weeks or so, or else surely one such restaurant would have popped up at most a block or two from where I live. And I have checked. So, to get more people to buy your food, you price your kaiserschmarrn something more reasonable, like $20.

So, the demand line is downward-sloping because if you priced the good very high, you would only be able to sell a little to the ‘schmarrnheads (don’t worry, it’ll become a thing), but if you price it lower, then maybe some people on the outskirts of the ‘schmarrn community will also go, and the true ‘schmarrnheads might go more regularly. However, you can’t tell who the true ‘schmarrnheads are, so you have to sell the price lower for everyone (there are only so many efficient ways to price discriminate, especially for a restaurant). This is how consumers — the people making up the demand line — are able to get good deals and feel happy with their purchases.

So far so good. However, there's a puzzle with this graph and how it is used that stumped me for some time during my first few classes in economics. My puzzle was this: in theory, we talked all about preference curves and how much people wanted something, but when it came time to draw the graph, the y axis was always price. This slippage between “willingness to pay” and “amount desired” seemed like an argumentative sleight-of-hand — a motte-and-bailey. I might love a good ‘schmarrn, but I would almost certainly have a lower willingness to pay than a Fortune 500 CEO with even the basest palate. If we say that the market is organized around how much people want something, and price signals match how much people want something with how much work it takes to make it, then all is good. But the difficult thing about people is that they are not only consumers, but producers as well. They get paid a certain amount of money and that amount of money deeply affects their “willingness to pay” outside of the actual desire for the object they might feel. The fact that the market organizes both labor markets and product markets would seem to make neither preference-efficient.

There is, of course, a patch-up for this critique: people make tradeoffs in the careers they decide on. A job, or perhaps a career path, is a bundle of attributes — wages, enjoyability of the work, necessary education/training, work hazards, financial risk, commute time, leisure time, cognitive/physical load, etc. When you decide how much you value wages relative to the rest, you are deciding how much you desire market consumption generally relative to other, non-market goods.

In this model, people who, for example, don’t want a longer commute time opt for jobs that may have lower wages. Since people make this tradeoff, goods markets are still preference-efficient in theory because the desire for consumption per se is priced in to the career decision.

Anyways, I guess that homeless guy looking for a job just didn’t like the commute time in private equity.

I will not say that the model is useless — because it isn’t — but it sure doesn’t seem right.

So there is an issue with the model — well, not an issue with the model. All models are wrong, so it’s not an issue with the model that it’s wrong. The issue is that we don’t know why it’s wrong. What is the part of the world that the model is ignoring in order to make the world legible? Why does that matter?

For this, we need to take a detour from classical economics to talk about something that makes the micro and macro nerds alike sweat: exploitation. That’s for next time.

If you are confused because your understanding was that inequality has risen, two points:

Pre-tax inequality rose by more than the redistribution of the tax code did (this is why the US is more unequal than many European nations even though the European nations are not generally much more redistributive).

Income inequality in the US started falling around 2014.

The number of pages in the Code of Federal Regulations is often used as a proxy for the amount of regulation in the economy. It is an imperfect one, because the stringency of regulations is far more important than the number, but that there is no mass deregulation or even change in trend starting in the 80s is the main point. The main site of deregulation, to the extent that it occurred, was specifically in the financial arena. See Noah Smith here under the section “Did the economy get deregulated in the neoliberal era?” for a fuller treatment. Important to note that even as finance was getting deregulated, areas such as housing and healthcare got far more regulated.

Guest vocals by a member of the B-52s, so I’m counting it.

This would, um, not be me. Most of the time.