This is a book review I submitted to a contest on the Substack Astral Codex Ten, a brilliant blog that I respect greatly and which is a member of the Rationalist community. The annual book review contests hosted by Astral Codex Ten are unfailingly impressive and insightful. My submission, unfortunately, was not nominated as a finalist or as an honorary mention. I enjoyed being able to participate and only hope that next year I will give myself more time to prepare, as I was rushed to both re-read the book in question and write my review of it. I am very excited to vote among this year’s finalists and was happy to see that a few of my favorites from the initial round of voting made it through.

I am posting my submission here, unchanged. I believe that the seal of anonymity required by the contest can be broken at this point and that I am not violating any sort of principle by revealing my unknown, pseudonymous self as the author. My only real retraction I would like to make is that at one point I assert that there is not much talk about philosophy in the Rationalist community. This was, on one level, not as nuanced a point as I had intended to make, and on another level, just plain wrong. So, apologies for that. Without further ado, my submission:

To create or guide a school of philosophy is a grand cultural achievement, on the level of creating a genre of music or style of architecture: the Greeks have the ancients, the Germans have their idealisms, the Chinese have Confucianism and Taoism.1 To contribute to these traditions, to have them spring up as a germ from the miasma of a particular culture and its traditions, is both an attestation to that country’s ability to produce greatness and an expression of that culture’s particularities. National myths may be myths, but gosh are myths fun — and sometimes revealing. A philosophy can be an expression of individual idiosyncrasies, a mirror of culture, a byproduct of history, and also, incidentally, an elucidation of true perspectives.[citation needed]

The Metaphysical Club is a book about pragmatism, the only fully home-grown American school of philosophy. However, the book is not a philosophical tract — it is a history of ideas. Part philosophy, yes, but also part history, part biography, and part social theory. It traces the development of pragmatism through the lives of its principal founders spanning pre-Civil War Boston to early-20th century Chicago. In this short time, America dissolved, recomposed, and found itself thrust into a modern, capitalist lifestyle. How did American society cope with the mass wreckage of the US Civil War? What changes in intellectual assumptions were necessary? The Metaphysical Club is a story about modernity, America, and a philosophy which sprung out of their terrible intersection in the wake of the most deadly war in US history.

…But Some Are Useful

This book review’s main purpose will not be discussing to what extent you should believe that pragmatism, as a philosophy, is correct. That will be a thrust, but one among several. My work in providing a plausible notion of pragmatism has been greatly aided by my selection of audience. To misquote Reagan, Rationalists are already pragmatists; you just don’t know it yet.

Philosophy and Cartography

I do not believe I have ever read, in one of these contests, a book review on philosophy (even as tangential as a book on the history of a philosophy). In fact, besides a healthy use of decision/game theory, generally AI-focused inquiries into philosophy of mind, and some discussion of applied ethics (generally in a consequentialist frame), I do not see much philosophy or philosophical works directly discussed on Rationalist forums at all.

I apologize if I am mistaken; I am far from being well-read in terms of Rationalist authors and forums. I also do not mean this as an indictment — nowhere does it say that philosophy must be discussed everywhere of note. However, because of the relative lack of focus on philosophy, and philosophy’s place as an oft-ridiculed subject, I thought I would make a quick point on its purpose.

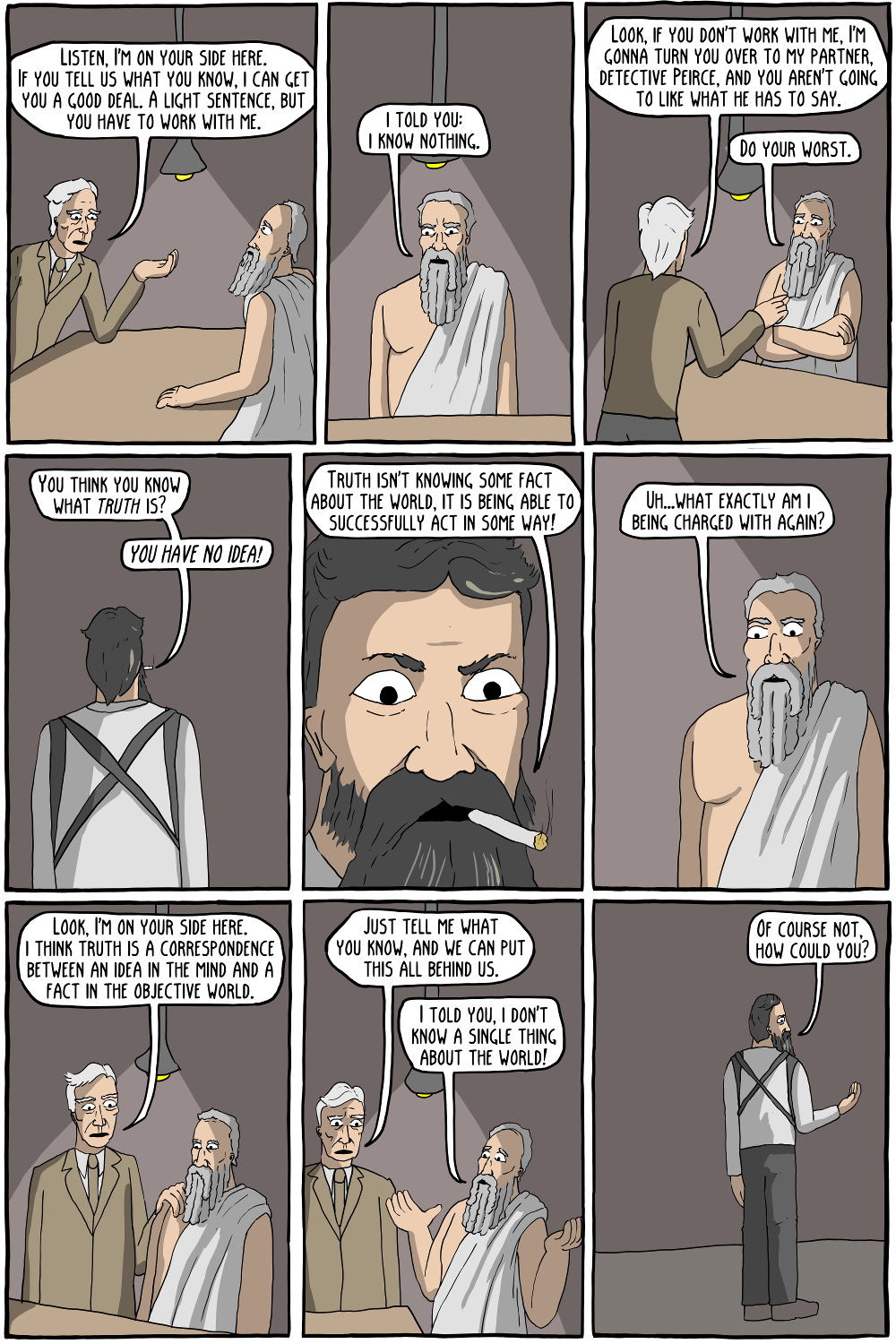

Philosophy is not about asking Big Questions; it is about conceptual analysis. A philosopher might or might not be a particularly clear writer or clever arguer, but the primary purpose of philosophy as its own discipline — what sets it apart from rhetoric or persuasive writing — is drawing out the implications of a concept or theoretical position. Largely, philosophy is centered on metaphysics (what is the nature of the world/its relation to our mind), epistemology (what is the nature of knowledge/truth), ethics (what is the nature of the good/morality), and aesthetics (what is the nature of beauty). You can also talk about logic (what is the nature of implication/argumentation), ontology (what is the nature of being/existence/nonexistence), philosophy of mind, philosophy of language, philosophy of art, and so on.

Fields of philosophy take some concept to be their object of inquiry — “the world,” “knowledge,” “good,” etc. Philosophy is the attempt to string out what that concept actually is, what it consists in, the various ways of understanding it, and the implications of all this stringing out. The Socratic method is nothing other than forcing your interlocutor to face the implications of their own concepts.

You have philosophical beliefs; we all do. Both ones you are aware of — “an action is good if it reduces harm” — and ones you may not be — “what is the nature of language?” There are certainly other reasons to read philosophy: you can read it to understand the intellectual assumptions of a time and place (i.e. backwards, as we are in large part doing here), to better understand another point of view, or to sincerely see if you find it persuasive or compelling. Reading philosophy can also be someone else confronting you with what you already believed, whether you realized it or not.

Modeling Truth

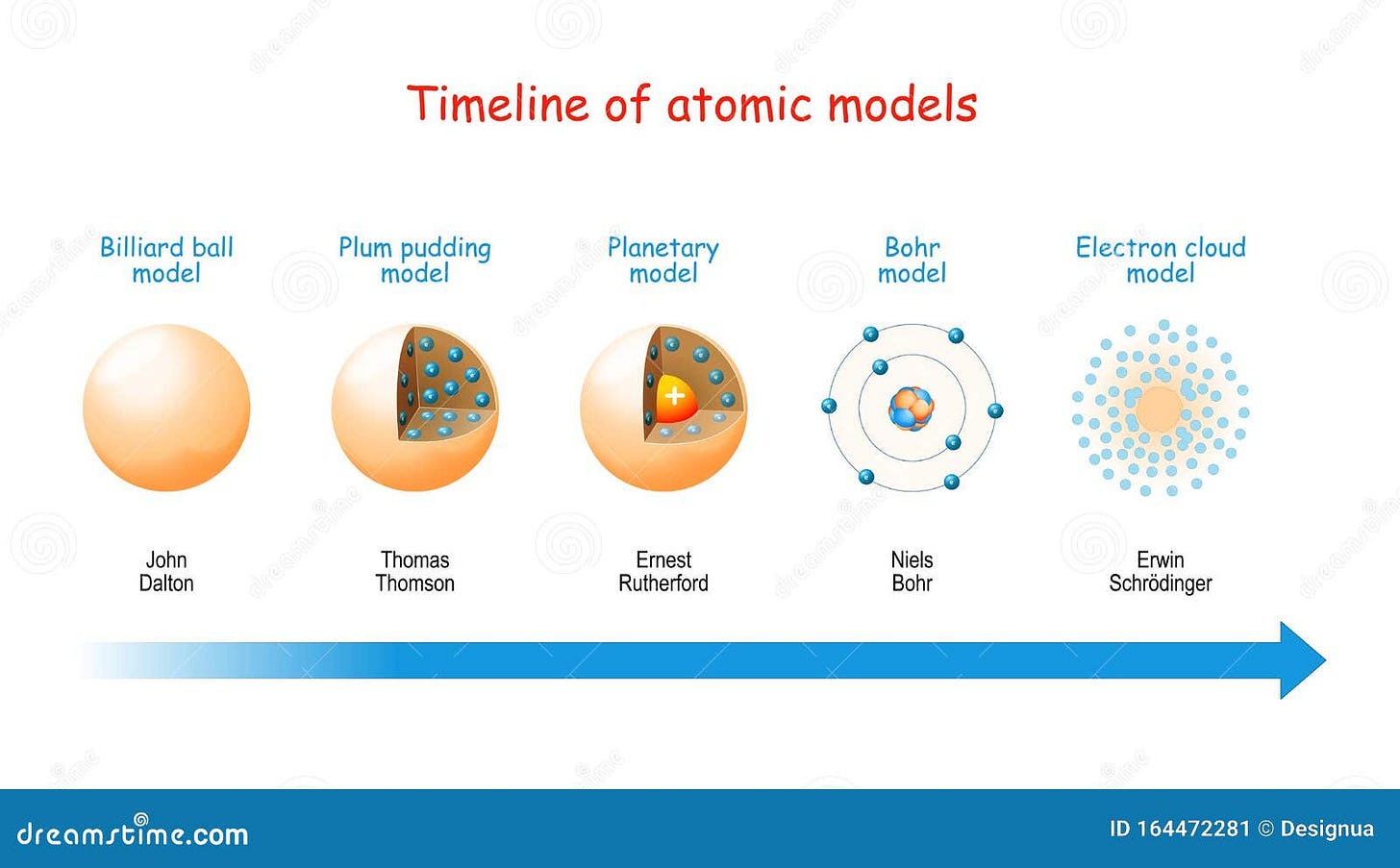

At some point in your childhood, probably around 7th grade or so, you may have seen a graphic that looked something like this:

At this point, we could extend the graphic to include Chadwick’s model including neutrons and the more recent additions of quarks and gluons. If we really wanted to, we could extend it backwards to Democritus’s hypothesized atoms and their hooks, sockets, and all sorts of strange qualities. But the question I want to get at is contained very neatly in this graphic: why did we move from Schrödinger’s model to Bohr’s? Why from Bohr’s to Rutherford’s? What is the relationship between these models and the actual atoms that we bump up against every day?

These are basic questions. We’ve read our Kuhn, we know that all models are wrong, and before each argument we read, we make sure to say the blessing over the map (which is not the territory). The thing you are describing is not simply captured by the paradigm or model or map that you use. It’s not that Bohr’s was false and Rutherford’s was true, but that Bohr’s model fit the territory in some ways but not others, while Rutherford’s model fit the territory in different ways that we thought were more helpful. We made our beliefs pay rent, and Rutherford’s beliefs could pay more rent than Bohr’s.

This process is not clean and obvious — Kuhn is sure to complicate the picture — but the overall method is that the models attempt to explain the world, perpetually fail, but fail in new and less discouraging ways. No model is ‘true’, in an unqualified sense — the map never reaches the territory — but we can talk about them being more or less true — the map does have a relationship to the territory.

We can expand the problem, though. It is paradigms all the way down — and in fact, we must go further. It is not just formal models which are never able to fully capture the world. All linguistic or conceptual knowledge is a model or paradigm of some sort or another, by mere virtue of its generalization/compression of information/stylization of facts. The concept ‘tree’ holds several things together by picking out various qualities and lumping them under ‘tree’. Yet in doing so, any actual use of the word ‘tree’ (trees have leaves, trees need sunlight, trees do this and that and the other) becomes separated from the territory. It is a model. And if all models are wrong, what does it mean for something to be true?

Getting from Territory to Map (and back again)

The map-territory relation is a truth function. The map is a concept, theory, or proposition, and the territory is the world. Truth is a property of a relationship between map and territory — between proposition and world. However, once you have distinguished language and concepts and propositions from the things which they describe, you need to explain how they relate.

There are two well-known schools of truth relations. Well, three, if you count deflationists, who have become popular recently in academic publications. They mostly just throw up their hands and ask everyone to stop talking so much about it. Which, ah, is an approach. Deflationists say that to say something is true is just to assert the thing. What does asserting the thing mean? That it is true. Mm. I’m sure there are a lot more words you could put here which make it sound slightly less embarrassing than G. E. Moore’s proof of an external world, but I don’t really care. Study something else if you don’t find the nature of truth interesting — you don’t have to try to ruin it for the rest of us.

The first, and most straightforward notion of what truth is is the correspondence theory of truth. The correspondence theory suggests that truth is a relationship between propositions and objects. What kind of relationship? Oh, I don’t know. They correspond. The concept says the thing that exists.

The second is the coherence theory of truth. Here, the truth value of a proposition is a different “specified set” of propositions. How do you know those propositions are true? “Well, they’re the specified set.” Okay.

From the map-territory relationship: the correspondence theory of truth either (a) question-begs or (b) collapses the distinction between map and territory; the coherence theory of truth implies that as long as your map is stitched together consistently, it is true.

Here is the dilemma: all the things we use to think about the world are distinct from the world. They cannot unproblematically “correspond” to the world (correspond how? Through more concepts?), yet truth necessarily is a relation between our concepts and the world, not merely their coherence with one another. Related: there are infinite valid logical arguments, only some of which are sound.

Here is, to a first approximation, the pragmatist dodge: “consider what effects, which might conceivably have practical bearings, we conceive the object of our conception to have. Then, our conception of these effects is the whole of our conception of the object.” I.e., all that a belief is is the rules for action which it entails. The truth of a belief is merely its capacity as a rule for action.

“The pillow is soft” is not true because “pillowness” and “softness” correspond to things in the world in some unproblematic way; nor is it true because “the pillow is soft” does not contradict some other thing we believe. It is true because when I say “the pillow is soft,” I expect certain things to happen if I act a certain way (e.g. if I drop a glass on it, the glass will not break), and when I act as if the pillow is soft, things go as planned. What is “the pillow is soft”? It is nothing other than what occurs if you act as if the pillow is soft. Remember: “all models are wrong” has a very important caveat: “some are useful.” The belief is the rent.

One way of thinking about this is that the only connection our concepts have to the world is through our acting under them. What makes a model true? Its capacity for use.

You can take this in a very cynical way — the useful idea which benefits me, e.g. everyone thinking this book review is great even if it is not — but that would be a misread. It would still be useful to me to have an accurate belief about the quality of my own book review so that I could predict how people will react to it and act accordingly. I would still try to believe true (in the unreflective sense) things, even if I wanted other people to believe untrue things. The cynicism is a moral question, not an epistemological one.

All knowledge is wrong, but some is useful.

Now, I have been saying “pragmatism is this,” “pragmatism is that.” Even the early pioneers of pragmatism did not quite agree with one another, and pragmatists have not exactly converged since then. There is not one pragmatism, but a plurality, a variety of directions that this idea has been taken. Each founder of pragmatism took the germ of something, built it up, and immediately began arguing over which way to take it. What’s more American than that?

Founding Philosophers

The eponymous Metaphysical Club, cheekily named against the contemporary grain of metaphysical quietism, was formed in January 1872. We know little about it — only one member ever wrote down a recollection of its existence, and that recollection occurred in an unpublished manuscript written 35 years after the fact. Nonetheless, it is clear that such a group was formed, and we can be relatively confident in our accounting of the membership.

The Metaphysical Club consisted of a group of young men, largely tied together by the webbed nature of early Bostonian intellectual culture (with Harvard University spinning much of the silk),2 who came together to have dinners and discuss ideas. In this way, it was not special — dining clubs were how much interdisciplinary cross-pollination occurred in those times. The Metaphysical Club was special because its members were the Founding Philosophers of American Pragmatism.

Like the Founding Fathers of the US Constitution, some of these individuals achieved great things in stewarding their creation and expanding its capacities; also like the Founding Fathers, some of them met unfortunate or undistinguished ends. These Founding Philosophers are recounted as such: Charles Sanders Peirce, William James, Oliver Wendell Holmes Jr., Nicholas St. John Green, Joseph Bangs Warner, John Diske, Francis Ellingwood Abbot, and Chauncey Wright.

It was in the course of The Metaphysical Club’s meetings that Nathaniel St. John Green introduced and insisted on the definition of belief as what one is prepared to act on. People purport to hold many beliefs, but anyone can say they hold beliefs; one can even say one holds contradicting beliefs. It is only when the rubber hits the road that we are forced to choose a direction. The principle of noncontradiction is a fact about the world. And importantly, a tire is not merely a reflection of the asphalt, but a tool for grappling with it. Beliefs are not passive mirrors, but a part of action themselves — their construction is itself an ingredient of action, and a motivated action itself.

Rather than separating belief from action, Nathaniel St. John Green demanded a purpose for belief, a connection with attempts to change the world. This belief came not through any background in philosophy — Green was a lawyer. No, he most likely picked up his great contribution to the history of philosophy in a book on criminal law.

I once heard someone describe philosophy as the studied misapplication of concepts. Nathaniel St. John Green may have produced the raw material of pragmatism, but he did not refine it, did not build with it. No, the gross misapplications of this core idea occurred only in the thought of the philosophers of the group: Chauncey Wright (to some extent), Oliver Wendell Holmes Jr., Charles Sanders Peirce, and William James. Each of these individuals had their own reasons for appreciating Green’s contribution, and their individual perspectives and motivations deeply informed each of their pragmatisms.

About this Weather We’re Having

Since Socrates, there have been philosophers who enjoy the conviviality of philosophy much more than the publishing of it. Perhaps the most successful and famous of these in recent times is Edmund Gettier. Edmund Gettier published two papers in his lifetime. One was for his PhD, and was impressive enough to land him an immediate position instructing philosophy at Wayne State University. As he was pressured to publish in order to retain his job, he wrote one of the most famous papers in all of analytic philosophy: Is Justified True Belief Knowledge? In three pages, Gettier took a definition that had been well-established since Plato — that knowledge is justified true belief — and demolished it. It was enough to earn him a position as associate professor before he turned 40. He never published anything else, but his love for philosophical discussion was legendary. While he never published anything else, he was credited in many papers for his help formulating their arguments.

If Chauncey Wright had been a more able writer, or a better public speaker, he might have had such a life. But he wasn’t, and he didn’t. Wright had a perpetually fascinating facility of spoken philosophy — anyone who knew him well wondered at his ability to discuss, and discuss fruitfully, on most any philosophical project. And he lived for speaking. He would often lumber into a friend’s room, sit down, and simply wait for them to broach the silence. At which point he would talk. And listen. And respond. His ability to form discussion groups and clubs (like the titular one) were relief from an otherwise deeply solitary existence. Without such opportunities for conversation, he would often fall into deep depressions, and his friends would take turns conversing with him. He was a lonely man. As it stood, he had neither a talent for academic writing or public speaking (reportedly, he was entirely monotonous while lecturing). Nonetheless, he was a brilliant interlocutor and an inveterate founder of clubs, and his pragmatism deeply influenced those Metaphysical Club members more lucky than him in temperament and circumstance.

Wright was a computer. His job was to do calculations predicting the future positions of various astronomical objects used for ship navigation. Through a combination of genius and drugs, he was generally able to do a year’s work in three months. The other nine were for talking. Like many of his contemporaries, he had lost family in the Civil War and, also like many of his contemporaries, he blamed the pitched rhetoric and idealism of the abolitionist movement for the bloodshed. He didn’t believe in much. He saw calculations succeed and fail, and he saw beliefs harden and turn into steel and blood.

Wright believed in weather. Roiling, unpredictable, without direction, and prone to extreme variation, yet at the same time entirely determined. Everything, to Wright, was some sort of cosmic weather. And if we could not even predict the weather, why were we attempting to predict, say, the course of human history? This was something far more complicated than mere clouds in the sky. To Wright, the social scientific theories of his time were just one more providential plan to have faith in. He held in special disdain those theories which attempted to supplant moral values (e.g. those of Herbert Spencer, the Social Darwinist) — even if you can predict it, weather is not good or bad, kind or evil, and living your life to the weather’s tune is more cowardice than virtue. In all this weather, everything is determined and nothing is determinable.

Wright did not believe in moral theorizing. While he disliked especially those who thought science could give them morality, he also held in contempt the creation of moral theories themselves. His skepticism towards high-flying ideals goes far:

Men conclude in matters affecting their own welfare so much better than they can justify rationally, — they are led by their instincts of reverence so surely to the safest known authority, that theory becomes in such matters an insignificant affair. … To stake any serious human concern on the truth of this or that philosophical theory seems to me, therefore, in the highest degree arrogant and absurd.

Of course, to such a thinker the pragmatic maxim holds a certain charm. The bringing low of abstractions meshes well with his thought, but the real intersection is a bit more subtle. If uncertainty is basic and certainty nonexistent, as a world of weather would necessarily be, beliefs cannot be judged on their ability to mirror the weather. Any belief which mirrored the weather would be weather itself, in all its unproductive qualities — roiling, unpredictable, without direction, and prone to extreme variation. Beliefs are — they must be — rules for action, hopefully as concrete and careful rules as we can get.

You might, however, see something of a double-bind in Wright’s thought: if morality cannot come from facts, and moral speculation is to be denigrated, what ought one to do? Are not our instincts but one more bit of weather? Wright didn’t have an answer: he had nihilism.

Wright died young: in 1875, a mere three years after the formation of The Metaphysical Club, with no professional distinction but many disciples to mourn him. He never achieved the heights of Oliver Wendell Holmes Jr. or William James, nor did he have the chance to cut as long a string of attempts as Charles Sanders Peirce, but he left his mark on their thought. It is from the sharp, concentrated sources of Wright and Green that we get the great works of Holmes, James, and Peirce.

Wounded

Before Oliver Wendell Holmes Jr. was on the Supreme Court, he lived the US Civil War. He lived the abolitionist movement before it and he lived the deadliest battles during it. He was an acolyte of Ralph Waldo Emerson, a student activist, an infantryman, a captain, and a casualty. In fact, he was a casualty three times — once at the tragic blunder of Ball’s Bluff, a second time at the deadly battle of Antietam, and finally in a skirmish called Second Fredericksburg (First Fredericksburg was already taken).

It would be wrong to describe the resultant change in his worldview as something ‘snapping’; it creates far too violent and undisciplined an image. Wendell Holmes was nothing if not disciplined. Besides, it gives a bit too much credence to his attempt later in life to clean up his biographical record. He attempted to destroy almost all of his correspondence during the war, presenting almost a clean break between his prewar abolitionism and his postwar regrets. It rather seems that with each of these bullets, one piece of his future thought struck him — glanced him, really. And it was only after the wounds had healed and he was off the field of battle that he could fully consider the changes these new instincts demanded.

Holmes’s first wound was his worst. An inch or two lower, and his heart would have been pierced by a rifle bullet. As it stood, he found himself lying in a hospital surrounded by mayhem wrought through incompetence and foolhardiness, wondering whether he might live. So, as one does, he considered whether he might want to change any of his beliefs. Here, he lost his certainty. For while he reflected on his beliefs, he also noted something strange. As he noted: “it is curious how rapidly the mind adjusts itself under some circumstances to entirely new relations — I thought for awhile that I was dying, and it seemed the most natural thing in the world — The moment the hope of life returned it seemed as abhorrent to nature as ever that I should die.” The essence of thought was not immutability, but flexibility. Certainty was a property of a mind constantly adjusting to its circumstances. A mode of thinking too rigid to allow the mind the necessary adaptations to new circumstances could not possibly cope with life. Relations change, the world shifts, and ideas must be remade to suit their situation.

Holmes’s second wound convinced him that war was singularly wasteful. Horrible, yes; deadly, to be sure. But he already knew these things. Antietam taught Holmes that war did not merely kill — it killed the bravest, the boldest, and the most capable. It is here that Holmes began to valorize the professional over the ideological. His muse, Henry Abbott, was an inveterate racist who did not believe in the North’s mission, yet fought with absolute bravery and complete professional compunction. In your platoon, it doesn’t matter how fervently someone believes in the mission — it matters whether they can get the job done. Would war even civilize the South? The North considered itself on the side of civilization, against the barbarity of slavery. There is an aggression to civilization, an intolerance to other ways of organizing society — many times, rightly so. Yet Holmes asks: is war not a terrible and terribly wasteful way to enforce civilization? Surely the advantage of the civilizing principle lies in peace.

Holmes’s third wound was slighter than the previous two, but it was the shot in the foot which broke the camel’s back. Holmes had changed. The promise he had made was, at this point, another person’s. His initial duty no longer held. He finished his campaign and did not re-enlist.

After the war, Holmes was still interested in philosophy — the fire which Emerson had initially lit in him still glowed, albeit a different, bloodier shade of red. He would do philosophy, yes, but without the navel-gazing — he would do scholarship, analysis, law. That was his entrance to philosophy. It was Emerson professionalized.

Holmes arrived at The Metaphysical Club with one overarching lesson from the most painful and formative experience of his life: certitude leads to violence. Or, as he later states in one of his most famous Supreme Court opinions: “when you know what you know, persecution comes easy.” Lurking behind the cynical professionalism and denigration of moral idealism is the same sensitive boy touched by the abolitionist movement: Holmes saw what violence really was, and he would do anything to keep others from having that same vision.

To such a person, it is quite easy to see the allure of pragmatism, especially infused with Wright’s nihilistic moral quietism. Ideas are tools, made by motivated people not merely as a reflection of the world but as a way to change it. As Holmes ascended the ranks of the US legal community, this epistemological notion took on a political and jurisprudential light.

For Holmes, politics was zero-sum. Groups jockey for more or less resources, build platforms to align interests or convince others that their own interests are more valuable, and fight it out in the democratic process. There is an old aphorism by Carl von Clausewitz, arguably the most influential military theorist in European history: “war is politics by other means.” Much of the political theory behind Holmes’s jurisprudence is based on an understanding of the obvious corollary: “politics is war by other means.” Holmes believed that the majority would get its way at some point, somehow. If they were frustrated by the political process long enough and with enough pressure, they would understand their own power — they would win the war. Holmes hated the ‘other means’ of war. He despised them. So he believed the political process should play itself out.

Sometimes when the Supreme Court was deliberating, Holmes would ask a fellow justice to name a legal principle — rights talk, cost-benefit analysis, precedence — and would proceed to decide the case in either direction using that principle. The point of this demonstration was not that Holmes was a brilliant arguer, though he was. It was that, as he says himself, “general principles cannot decide concrete cases.” The fidelity of the world is too high; there are too many facts. Beliefs do not mirror the world. Enough facts can be marshaled in favor of one direction or the other such that any general principle can weigh them up in any direction. How are cases decided, then? Experience. Culture. Judgment. Any pretense that there is some single essence to the law or even that having one essence could mean that any case could be obviously decided is farcical. It is motivated reasoning that is blind to its own motivations.

When Holmes was on the Court, laissez-faire capitalism was the jurisprudential theory of the day. The Supreme Court believed that the Constitution’s protection of the right to due process included that of making contracts. Since almost any economic regulation could be spun out as infringing on the right to make contracts, early Progressive Era attempts at ameliorating the social difficulties of industrialization were met with an uncompromising Supreme Court. Here, Holmes’s judicial restraint — his belief in letting the majority have their say — made him, somewhat to his bemusement, a lion of the left. He enjoyed the attention enough to not dispel the misunderstanding, but it is also true that his influential opinions laid the groundwork for the possibility of any level of the US government to shape economic growth.

Holmes wore the mask of a pragmatist over that of a cynic over that of a pacifist. A different sort of pacifism than we are used to, to be sure, but a pacifism nonetheless. To wear a mask is not merely to deceive, but also to take on the character of the mask. Holmes was a pragmatist and a cynic and a pacifist. Above all, though, he was a soldier.

Order ab Chao

William James, much to his shame, did not serve in the US Civil War. He considered it, and like most decisions in his life, he decided it many times and in many different directions. But while his father likely would not have wanted him to enlist — James’s education was a major project and investment for him — James also did not plead any case too hard. See, the father of American psychology, as he is sometimes called, was somewhat tortured when it came to closing off possibilities. He hated certainty, and the destruction of possibility that decisions entailed. He also felt that decisiveness was a virtue, and that if one at least made an attempt, the universe would (Louis Menand’s words) “meet such a person halfway.” To marry the two, he inculcated an impulsive decisiveness — push in one direction thoroughly and single-mindedly, with the understanding that he could change his direction at any moment.

James endeared himself to many people with his passion and personality, but there were frictions, especially in cases that required commitment. I will not relate the story of his courting of his future wife, but let it be known that it was, in a strange way, comforting for me to see someone act with such obvious lack of suaveness (suavity?) and still having it all work out well enough.

James’s world was chaotic — even from childhood, as his family moved constantly (ostensibly for his own educational benefit). This pained him, and he struggled with depression at various times throughout his life. Nonetheless, even through his own indecision and his families uprootedness, he could construct a life. It was a strange one — he studied painting and chemistry, among other things, before landing on psychology — but it was his.

It was while studying natural history that William James read Darwin’s On the Origin of Species. Similar to Chauncey Wright, it had an immense effect on him. The metaphor was obvious: out of a random process, order was born. It was on difference that survival depended — the longer beaks, the shorter wings, all these abnormalities were what allowed adaptation, and therefore survival. Rather than essential types that individuals deviated from, the world of natural selection is a buzzing confusion of chance, change, and difference — in fact, it is the very confusion which creates the types in the first place! “Order from chaos” may not even be strong enough — the chaos is part of the order, and the order is part of the chaos. And this was the elegance of Darwin’s theory, for James: it is the nature of the world to provide exceptions and variance, yet not only could Darwin’s theory hold up to exceptions and variance, it actually anticipated and even required them.

James, perhaps as well as anyone else, understood the nuance of Darwin’s theory. He did not fall for the Social Darwinist trap of giving ‘evolution’ a progressive connotation — natural selection is just what survives; it is not right or wrong for doing so. He also did not fall for the customary defense that Darwinists proposed when they offended the religious — i.e. to plead irresponsibility, that a scientist just has to stick to the facts.

Darwin’s theory does not just ‘stick to the facts’ — it actively creates facts through its interaction with the data. The problem is not that anti-Darwinian scientists are too motivated by their theories to just see the facts as they are — the problem is that their theories are disconnected from the facts and their facts are disconnected from the theories. The two do not touch. The best such a theory can do is contort itself into a mirror of what is already known.

To go one step further, James believed that all inquiry was motivated — by tastes, values, hopes, grievances, by all things high and low in human nature. Science was no different. This does not mean we do away with reasoning and science — rather, it makes the scientific process of continual cross-examination and high standards of evidence yet more important. All scientific conclusions are no more holy than any of our most common motivations because it is most commonly for those very motivations that we seek them out, strapped to narrow desires and narrow methods. The necessity of balancing multiple perspectives and allowing them to weigh in on the case is what James meant when he introduced “pluralism” to the English language.

Unlike Wright and Holmes, James felt a deep concern for the possibility of religious concepts like God and free will. Science’s mechanistic explanations threatened something important, he believed. His touchstone for this was a philosophical book he found while in the midst of a severe depression. It argued that if determinism is true, then all our beliefs are determined and we cannot explain, in terms of truth, why one person believes in determinism and another does not. So, the only noncontradictory belief is to say that we believe freely. James seems to have been taken by this argument (I am less sure of it).

When James arrived to The Metaphysical Club, he quickly adopted the pragmatic maxim and expanded it further than any of the others. For James, pragmatism meant that you should believe anything that makes a practical difference for you. Beliefs are tools for you to make the best of the world. We may have not been created intelligently, but the fascinating aspect of our situation is that an unintelligent process — natural selection — created intelligence. Natural selection may not be able to choose, but we can. And you can choose to believe — if a belief will allow you to cope with the world, to come to terms with it, then James says you should believe it.

Truth is expedience — truth, as James once said, happens to an idea once it is borne out by events. James, in talking about God and free will, becomes the most relativistic of the group: if believing in God and free will get you the results you want, in the most general sense, then they are pragmatically true. Beliefs are rules for action, ways to cope with the world. Everything else we might like about a belief — its parsimonious quality with other beliefs we hold, its relation to the latest scientific understanding, its ability to be expressed clearly and concretely — are mere proxies for the actually important quality of a belief: the actions it produces.

Holmes and Wright both thought James’s view as repellently soft and incomplete. Holmes, in a sharp turn of phrase, once said that James’s “wishes made him turn down the light so as to give miracle a chance.” In their view, if James could have the courage to think a little more clearly, he would see that all this God and free will stuff is bunk keeping him from greater clarity in his rules for action.

James, though, can play a similar game. James pegged Wright’s nihilism as his way of coping. What is Wright’s aversion to moral speculation other than a vote against the civil war which killed his brother? There could be a similar argument for Holmes, as I have made above. What is his judicial restraint except a similar vote against the civil war which left him with so many fewer friends and so many more scars? Just because their ways of coping deny things — morality, social improvements through politics — instead of affirming them does not make them any less motivated or personal. It just means they act for different reasons.

The Devil’s Arithmetic

Charles Sanders Peirce was a fuckup. He is probably the only subject in the book I honestly think I would have found insufferable. Brilliant enough, sure, but also cocky, ungrateful, and impulsive — and deeply racist to boot. For a decent chunk of his life he got a government job due to his father’s facility at networking, and for the rest of his life his main output, next to an unfinished philosophical system, was the CO2 from all the bridges he burned. He was terrible to his wives and ungrateful to his friends. Menand makes the point that he was self-aware. I give him very little credit for his this, as the only purpose of self-awareness is to actually change the things that you do to hurt people. He did not. His life was a tragedy, except he had so many tragic flaws that only when he is reciting a paper do you forget that you’re probably rooting against him.

Apologies. That was quite mean. Fun to write, I admit it, and certainly truthful, but largely unhelpful. So Peirce is scum. What else would you expect from a statistician.3

Here’s a 19th century scientific discovery: 19th century atronomers make errors when measuring the positions of stars (not interesting) which cluster around, in a regular pattern, the true position of the star (interesting). The consistency of this pattern and its ability to reveal, through repeated attempts, the correct position, is called the Law of Errors. The Law of Errors was the foundation of Peirce’s thought.

Under the Law of Errors, Peirce could see, like many others, how variance itself could be regularized. It had, in sum, a somewhat similar effect to that which Darwin had on James. However, Peirce went further. Since variation itself was regular, Peirce believed that it could become more regular. In short, he believed there was something called “pure chance” at play in the universe, and that this was as fundamental as any law we could create — yet it would trend towards certainty. He had a modern mind, but inherited his father’s deeply premodern idea.

Benjamin Peirce believed that the world was made to fit to our minds, that there was an intelligent correspondence there which showed God’s providence. Charles Sanders Peirce believed this as well. The project of his life was a matter of marrying indeterminacy with intelligibility. The solution Peirce attempted (or, at least, the one amongst several which he most staked his claim on) was to come at Pragmatism from the other direction.

There were two demons which haunted the 19th century scientific community. One was the creation of French scientist Pierre-Simone Laplace. Laplace supposed an intelligence with the capacity and perception to know all the forces, laws, and substances which comprise nature. Then, he concluded, such a being would know everything there is to know about both the present and the future. This is Laplace’s demon — the instantiation of determinism. Probability is a human, not cosmic, matter. James Clerk Maxwell disagreed. He supposed two chambers with an atomic-size opening between them, and a Laplacian demon which could at least follow each molecule as it moved. Then, the demon could, without expending work, only allow faster molecules into one chamber and slower molecules into the other. This however, would violate the 2nd law of thermodynamics.

Violations of laws are not really supposed to happen in physics, the idea of this being that even things we consider laws like the 2nd law of thermodynamics are, under a certain understanding, probabilistic. But what does it mean to know things in such a world where everything is shot through with probability and the same antecedent never occurs twice?

Peirce makes a move common to the 19th century: he replaces the present God of his father with a future God of progress. Truth is that conclusion which all rational inquiry must ineluctably converge on. Truth is not a function of the individual mind mirroring reality, but the attempts of many minds converging — Law of Errors-style — on reality. He also made a cosmological move: as the universe ages, the better-behaved bits survive and the worse-behaved bits are flung out away from us — e.g. substance which does not abide by gravity will not be in our solar system for long. So over time, the universe itself becomes more regular, mirroring our ideas.

Hegel thought truth would come at the end of the Idea sublating itself through its own contradictions; Peirce thought truth would come at the end of the universe and humanity looking at stars enough times to find the natural limit of the Law of Errors. He also believed this would have something to do with making people less individualistic as well — they would start to think more like one another, and humanity itself would become less petty and provincial. It is a statistical eschatology.

A Philosophy Fit For Modernity

Holmes, James, and Peirce each had their lives and thought marked by those three harbingers of modernity, each more terrible than the last: war, chaos, and statistics.

The changes wrought on US society from the Civil War are difficult to comprehend. It is easy to think that the alienation of modernity stems from a lack of provinciality, a sense that one is from nowhere. This is backwards. Humans are provincial beings, whether geographically, socially, or institutionally. Is the Davos crowd any less provincial due to their country-hopping? I would argue not — they are merely provincial on a different axis. The sense that geographic provinciality is somehow special I also disagree with. Premodern humans were often nomadic, migrating and shifting their social and geographical organization.4 Humans are provincial or we are atomic — we may have overlapping and complex provinces, but we are necessarily provincial. The world is just too big otherwise.

No, modernity is not a lack of provinciality, but a recognition of one’s own provinciality — it is the knowledge of the provisionality of everything, both spatially and temporally. From Holmes:

Holmes once remarked to Lewis Einstein that the war had made him realize that Boston was just one American city. He had not fought for Boston; he had fought for the United States, and the experience taught him that the two were not the same. Boston was not, as his father had loved to proclaim, the measure of all things. … The views of a Bostonian, insofar as they were Bostonian views, were partial and provincial. This realization was liberating, but it was also alienating. It inspired Holmes, in his mature thought, to attempt to transcend the prejudices of his own time and place. On the other hand, it left him at home in the habits of no time or place.

Holmes watched the world he grew up in — the world which, in many ways, he was a prime exemplar of — die on the field of Antietam. Holmes never had any children — he could accustom himself to what he felt were the necessities of modernity, but he did not wish to visit such a discipline on any new life. Holmes saw the old ways kill themselves for four years. The only way out was through, but ‘through’ never felt quite right.

Modernity means progress and provinciality — the concept of provinciality is not comprehensible in a premodern paradigm. The knowledge that all ways of working, thinking, and even relating are provisional by both border and generation is what is both so alienating and freeing about modernity. Culture becomes your culture, and one that shifts and moves forward — as it must. You lose the authority of a single script and gain the possibility of authorship. Pragmatism is, in one direction, the philosophy of a group of people desperately coping with modernity, attempting to change the deep intellectual assumptions of a premodern existence.

Modern Science

Modern science began when Darwin killed teleology.

Before Darwin, there was Louis Agassiz. Agassiz helped create modern American science, and then was destroyed by it. He came to America from Switzerland to lecture, a captivating speaker and an able networker. He drew massive crowds. Harvard University’s Lawrence Scientific School was created for him. He became the most well-known scientist in the United States.

Agassiz believed that all organisms had lived in roughly the same proportion in roughly the same places for all the time they existed. Fossils were remnants of previous attempts of God at creating the world, which of course He was done with now that He had created us (humans). What about colonialism? Good question. He had rationalizations for that. He also believed that animals, in the process of embryonic development, recapitulate the progression of their family. E.g. a more progressed mammal, in the process of its development, reaches the stage of each lower mammal. This, of course, is a sign of God.

I gotta say, people ate this up. They loved it. Everything made sense. The theory fit what they knew. Of course, what they knew was bad. They just didn’t know that. How Darwin’s theory beat out Agassiz’s (and those like it) was in large part by changing what good science was. Agassiz’s theory ended inquiry — there are no further questions to answer. Darwin’s theory provides a research project — what are the patterns of natural selection? How do various mating practices in animals affect it? How do certain physical features come out of natural selection? You need further questions. You can have an incredibly elegant paradigm, but if it doesn't lead anywhere, it's probably just string theory.

On a more fundamental level, the shift from Agassiz to Darwin was one from an intelligent universe to a statistical one. Without an ideal type — the product of an intelligent Creator — to compare to, species must become relational and probabilistic. Your questions become “what other individuals is this similar to (and to what extent)?” or “which can it copulate with?” Questions become more material than systematic — Agassiz’s research questions concerned essences and purposive organization, while Darwin’s concerned predictions and causal laws.

Looking for meaning to be already stamped onto the world is a premodern disposition — modern science has a different way of thinking. Scientific ideas become provisional and statistical rather than essential and theological. They do not give us guides to values, because they are not signs of God; they are just models. And all models, as we know, are wrong.

The Metaphysical Club: TNG

Modernity is a complicated, dangerous, and uncertain game. It demands ever-larger forms of cooperation, creates ever-easier ways of killing ourselves, and refuses ever-more demands for absolute knowledge. Why play it? Oh, I don’t know. Ask Sam[]zdat, I guess. Or Marx. Or Stephen Pinker. Or…

I guess my point is that a lot of people have asked this question. It’s an important one. But pragmatism is not an answer to the question of why modernization happened or whether one should or should not like it. It is an answer to the question of how to respond. Because modernity is here. Progress will stop when people stop wanting to get richer, when governments stop worrying about national security, and when society stops reacting to itself and its changing circumstances. The question for us right now is not solving it, but coping with it.

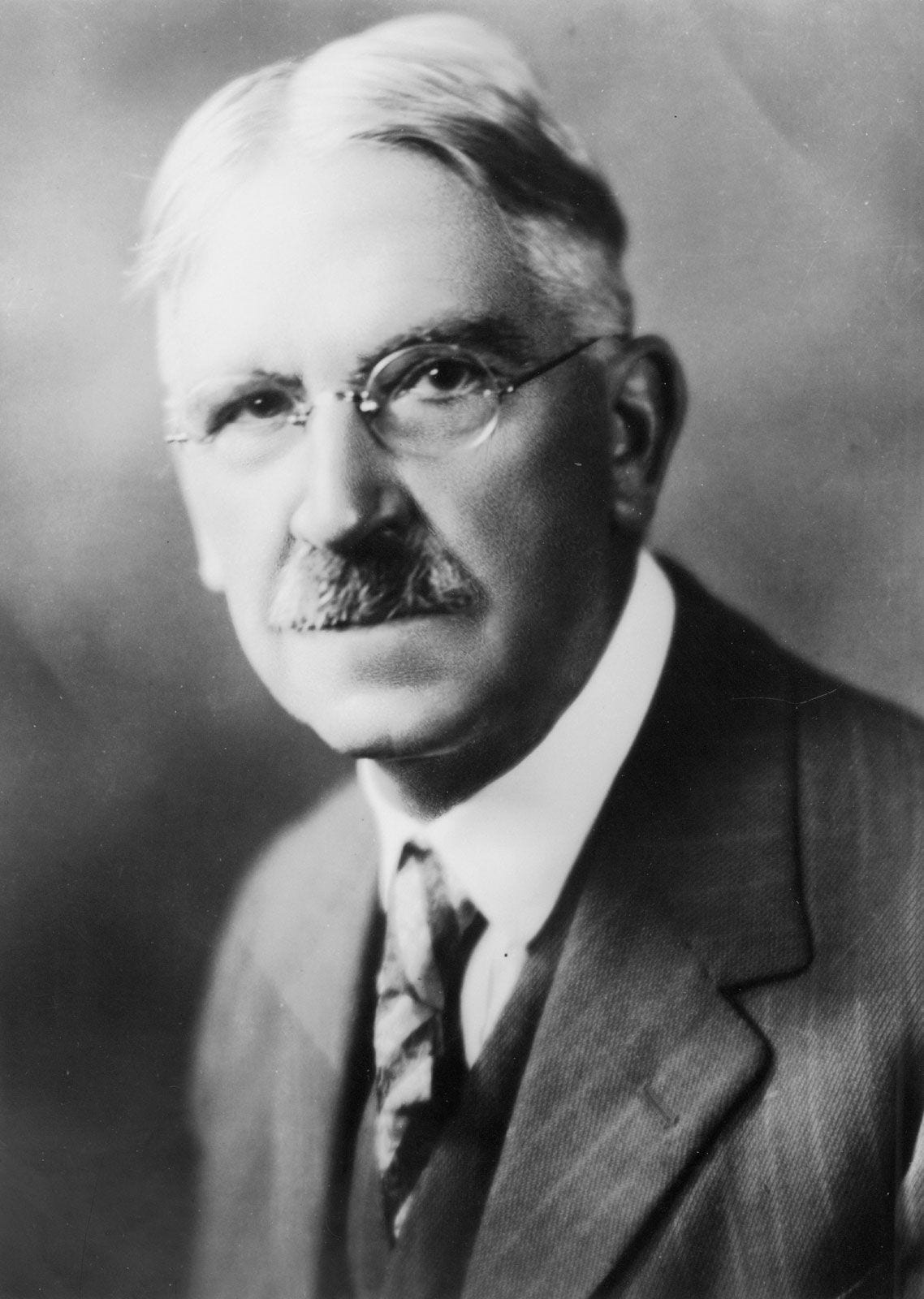

Oliver Wendell Holmes Jr., William James, and Charles Sanders Peirce never felt at home in modernity. They experienced the wretched snap of their world becoming untethered, beginning to drift. Yet they fashioned a tool: pragmatism. It was enough to help, but it required someone native to the new world to fulfill its promise. Enter John Dewey.

John Dewey was arguably the most important US public intellectual of the early 20th century. But before that, he was a young philosopher, born in 1859, who never knew a pre-Civil War America. His path to being a philosopher is a bit more regular than his pragmatist forebears — as perhaps befits a more modern man. He studied the German Idealists — principally Hegel — and then studied with the American Pragmatists. In fact, he had some sort of educational correspondence with each of Holmes, James, and Peirce.

Deeply mild-mannered, with a sense of equanimity that seems to have confused his elders and entranced his juniors, Dewey prized above all else the ability to adapt and find satisfaction in one’s circumstances. This did not mean a quietism about anything, least of all politics, but it also steered him away from any sort of militant socialism that viewed modern institutional paradigms as necessary evils. His metaphor of choice was the organism — a collection of interdependencies which worked first as a whole and only second as parts. He sometimes referred to the “social organism” and the idea of the whole which precedes the parts is central to his thought.

Assuming that the parts precede the whole is sometimes called the empiricist’s fallacy. To wit, does a shortstop precede a baseball game? No. One’s status as a shortstop only exists due to the baseball game’s presence. “Shortstop” is not a fundamental descriptor of you in isolation; without the game, you’re just a weirdo standing in a field.

Contrary to the empiricist’s fallacy is the idea of the organism: interrelated parts which only make sense in the context of one another. The large intestine only makes sense in the context of the stomach, blood only makes sense in the context of the lungs, the brain only makes sense in the context of the spine. Nathaniel St. John Green once said that things are unique before they are alike — i.e. we have to actively group them together, to burnish concepts as attempts to guide action. Dewey goes one step further: things are whole before they are unique — i.e. before we pick out what “things” are, we are confronted with a unified universe soaked in interrelations.

An example: John Dewey wrote a short, technical paper reacting to a concept in psychology called the reflex arc. The reflex arc, as a model of the human mind, posits a continual process of stimulus (seeing a flame), idea (“let’s touch the flame”), and physical response (reaching to touch the flame). From here, it supposes a clear, linear, mechanistic mind. It pretends to be a mere description of what occurs, when it actually is an active analysis of experience. It is only, Dewey argues, after one reaches out one’s hand that the sight of the flame becomes a stimulus. For the interpreter, the response precedes the stimulus — the stimulus only exists as such due to the response occurring. As Menand puts it, “the child wasn’t seeing and then, as a separate act, touching; the child was seeing-in-order-to-touch.” Action is not a series of smaller acts, but an organic circuit. It is whole before it is many.

Dewey’s famous educational program (which, when bequeathed to followers less careful and more ideological than he, turned into the progressive education movement) was in fact based on this pragmatist insight: knowledge should not — could not — be separated from action. For knowledge and action were not, rightly, separate processes of the mind, but rather parts of the whole knowing-in-order-to-act, acting-in-order-to-know circuit. We do not even strictly know in order to do or do in order to know — doing is why there is knowing and knowing is why we can do. Both are part of the single process of making our way through the world the best we can. Before it became “child-directed” or whatever, Dewey’s educational platform was pragmatism: uniting knowledge with action.

This dissolution of a pretended distinction to show a more complete whole is emblematic of Dewey’s thought. He was a thinker in the mold of Hegel in that he enjoyed few philosophical moves more than to reveal hidden assumptions and dissolve them. Especially assumed hierarchies. He was an enemy of all invidiousness. Especially with regard to action and thought, a hierarchy he believed was built on a class distinction.

Modernity means impersonal authority, hierarchical organizations, bureaucratic machinery, and mass markets. It means larger wholes and smaller selves. John Dewey was a near unique case in being a serious thinker of his time at home in modernity. This adaptability and aversion to division I have to imagine played a role.

Democracy All the Way Down

Pragmatism is the philosophy of democracy — not of individual rights, nor of electoral politics, but of the democratic ethos, what Dewey called the practice of “associated living.” Democracy is not just going to the polls and each individual having your rights — it is cooperation on a basis of tolerance and respect.

For all of the pragmatists, thinking was social. Wright was an obsessive conversationalist. Holmes argued on the Supreme Court for the sanctity of freedom of speech not because the right inhered in an individual but because the experiment of democracy demanded humility towards one’s own most certain notions and the contribution of each member to the whole. James credited his pragmatism clearly to the influence of Peirce and the others. Peirce believed that truth could only be known by group-level attempts at knowing.

On the level of the individual, we are feeble and ridden with biases. In 2001, Jonathan Haidt authored a paper called “The Emotional Dog and Its Rational Tail: a Social Intuitionist Approach to Moral Judgment.” It argued that it is rare for moral reasoning to cause moral judgments. Rather, moral reasoning far more often works as a post hoc rationalization of our moral intuitions, the reflection of which is provoked by social stimulus. Our own powers of rational argument are just not very good at getting us outside our own intuitions.

Haidt frames this quite negatively, but to me it seems reasonable: one should not think of intuitions as separate from rationalizations. Rather, the same mind which produces the intuition also produces the rationalization. Or, even more reasonably, this confirms further the social dimension of thinking. Thinking in isolation breeds consistent biases. The solution is the wisdom of crowds on a smaller, more granular scale. We rely on others to supply their perspectives, see our blind spots, and correct our mistakes. The solution is not just stronger tails, but more dogs.

More dogs means more differences. It means pluralism — in ideas, cultures, practices, and more. The democratic ethos must be plural. Yet it cannot merely be the pluralism of the parade — each idea to its own float, courteously applauded as it travels behind one and in front of another. It must be the pluralism of the orchestra, various instruments playing in harmony and enriching the sounds of one another.

In metaphor, this is all well and good. The actual practice of associated living is more difficult. Holmes’s famous defense of free speech gives some sense:

If you have no doubt of your premises or your power and want a certain result with all your heart you naturally express your wishes in law and sweep away all opposition. … But when men have realized that time has upset many fighting faiths, they may come to believe even more than they believe the very foundations of their own conduct that the ultimate good desired is better reached by free trade in ideas…. That at any rate is the theory of our Constitution.

Those who do not understand democracy may denigrate it as decadent or weak, but associated living takes discipline, work, and a seriousness that is not always appreciated, and certainly not always practiced.

Pragmatism reminds us that no one has it right in an unqualified sense, and with each earnest attempt (even a bad one), we get a better idea of the goal. Thinking is of a piece with acting, and action is inherently imperfect, composite. All actions occur in a world shared by others, just as all of our thinking is part of the same thinking. Your thought is necessary to my thought, even when I define my thought in opposition to yours. I must accept it — on some level — as part of the democratic process.

Freedom and Community in the United States

Time for contemporary speculation.

Abolitionism was not a political movement. Abolitionism was an antipolitics — it drew its power not from engaging in the political processes of gaining state power, but by the moral purity it could retain by not engaging in those processes. Abolitionists burned the US Constitution; they did not study it for tactics. One abolitionist bristled at an antislavery politician’s suggestion that an abolitionist had any moral duty to vote for antislavery candidates. Abolitionists were sick of politics: “gradualism in theory, is perpetuity in practice” was their motto. Slavery would end by radical action and moral condemnation/suasion, not petty politics.

We are at another point in US history when moralism is riding its high horse through the public streets. I am fairly convinced that the edge of the 2010s is wearing off, but that could easily change in November. I hope that nothing like the Civil War is headed our way, but if nothing else, this book is a look at one way America, at one point in its history, built itself back up out of the rubble of its previous societal structure: through its ideas.

The Turnings

There’s a theory of American history that suggests I should not be so maudlin about the dangers of the next few years. That theory is William Strauss and Neil Howe’s The Fourth Turning, one of my favorite social science “theories of everything (US related).” About every 20 years, America goes through a “turning,” changing the cultural, personal, aspirational, and political aspects of the nation. Turnings come in cycles of four, roughly 80-100 years long, called saecula. Each saeculum has a High of weakening individualism, strengthening institutions, and the invigoration of a new civic order while the old values atrophy; an Awakening of passionate spiritual upheavel, where a new set of values arise to challenge the old; an Unraveling, where strengthening individualism and weakening institutions decays the old civic order and a new set of values begins to take hold; and a Crisis, where upheaval in secular events concurs with the replacement of the old civic order with a new one. Honestly, I would just read the link in its entirety, but here is their prophecy from 1997:

The next Fourth Turning is due to begin shortly after the new millennium, midway through the Oh-Oh decade. Around the year 2005, a sudden spark will catalyze a Crisis mood. Remnants of the old social order will disintegrate. Political and economic trust will implode. Real hardship will beset the land, with severe distress that could involve questions of class, race, nation, and empire. Yet this time of trouble will bring seeds of social rebirth. … Sometime before the year 2025, America will pass through a great gate in history, commensurate with the American Revolution, Civil War, and twin emergencies of the Great Depression and World War II.

The risk of catastrophe will be very high. The nation could erupt into insurrection or civil violence, crack up geographically, or succumb to authoritarian rule. If there is a war, it is likely to be one of maximum risk and effort—in other words, a total war. …

Yet Americans will also enter the Fourth Turning with a unique opportunity to achieve a new greatness as a people. Many despair that values that were new in the 1960s are today so entwined with social dysfunction and cultural decay that they can no longer lead anywhere positive. Through the current Unraveling era, that is probably true. But in the crucible of Crisis, that will change. As the old civic order gives way, Americans will have to craft a new one. …

Thus might the next Fourth Turning end in apocalypse—or glory.

The US Civil War was one such Crisis. We are, supposedly, neck deep in another. I can make some prognostications about in what fashion the other shoe is likely to drop (war with China, authoritarian constitutional crisis) or if it already has and we just got lucky with an easy one (Trump’s one term, COVID, George Floyd protests), but that’s not the book. The Metaphysical Club isn’t about the Civil War and the social troubles that went into it and came out of it — it is about the intellectual milieu which provoked it and the changes in intellectual assumptions it caused. It is about the creation of a new set of values.

Inside of America there are Two Wolves

Abolitionism drew on the time-honored American tradition of idealist individualist moral anti-institutionalism, and in doing so helped send the country to war with itself. Its focus was on freedom, the individual conscience, and moral purity. The pragmatists were burned by these values — badly. For the most part, they had believed in them, as those burnt worst are always the closest to the flame. The set of values they produced were no less American, but were entirely opposed to their predecessors: interdependence, the social organism, and moral quietism.

As much as America is the land of the free, we are also a nation of joiners. Visitors to the land as far back as Alexis de Tocqueville noticed the importance of association and communal organizations to the early functioning of US democracy. This is not contradictory: cultures are by no means monolithic — they have all the strands of a grand tapestry, each waiting to be picked up by some generation or the other in a time of need.

The watchword in youth culture right now is community. I know this because I am currently in a communal home living with nine other people in their early 20s that range from left of me to very-much-to-the-left of me.5 And also because I have a pulse. In the 1960s and 70s, the student movement preached freedom. Freedom from the restrictive society of their parents, from sobriety and prudeness, from the machinations of industrial society. If they were communing with something, it was nature or God or the spirits — not each other. Now, social justice (don’t skip the first word) preaches solidarity. We are embedded in a racist society and accrue that racism ourselves through the unconscious. We must seek out community and ally with communities. These are not hippies breaking away from their restrictive parents, but community organizers looking for a community they can organize. They are alienated, not restricted.

Layered onto this generational picture of the turnings are the various threads of American culture: freedom, equality, community, ambition, etc. At any point, some are more salient than others, but they are all always there, ready to be picked up and used. It is just that it takes a while for the pathologies of the reigning values to become untenable, and only then will people willingly break their own values — their own self — in hopes of something better. We are headed, like the pragmatists, towards a more communal, less individualistic (in the commonsensical manner) America. Pragmatism is the past, but it might also be the future.

Repairing Our Faults

Let’s make some predictions. Here are some social pathologies which I feel like I can reasonably string back to the presiding set of values: NIMBYism (right to stop construction you don’t like), unhealthy internet use (individual free speech concerns), gun violence (SCOTUS finding an individual right to bear arms), loneliness (lack of communal participation/responsibilities), and economic dislocation (the free market of individuals will provide without central communal control), lack of climate change (free rider problem). Maybe you can think of more such stories. In general, I would say that in areas where the common good butts up against the individual, more concern will be given to the common good and national purposes going forward.

On the intellectual level, I doubt the focus on group-level racial equality can last. It seems, if nothing else, politically untenable.6 Already, its prophets of racial reckoning are being replaced with the sort of sensible people who turn utopias of the future into slightly better nows. Nonetheless, its primacy in contemporary discussions of race relations is one piece of evidence for my thesis. I don’t know what comes next, but I expect it to have some resemblance to the pragmatists. Backing down from high-flying abstractions and clear principles (free market fundamentalism’s quick fall from grace?) and getting into the difficult and practical realities of now, holding our ideas in a bit less credulous of a light.

It is on this intellectual level that I see the story of pragmatism as most useful. This is an American philosophy of interconnectedness and communal priority. It does not require the dissolution of rights, and it does not imply nationwide harmony. We remain a contentious people, flung to disparate corners of a country too beautiful for our practical-mindedness to deserve, attempting to be free individuals associated in a communal project. We are believers, doers, joiners, leavers, tinkerers, visionaries, Christians, Jews, Hispanics, Asians, moderates, radicals, Texans, Californians, New Yorkers, Las Vegasites, and even Patriots fans. We are misfits and conformists attempting to build a country for both of us. The last set of values didn’t work — let’s try new ones.

The next set of values will have its pathologies as well — for instance, I hope that the increase in censoriousness is a passing matter of pitched times, but it is possible that decreased license for speech will be a factor for the rest of my life. And certainly, this is not determined beforehand. The winds will blow, but a ship can sail in any direction. Culture is weather, prone to intense variation; culture is evolution, shot-through with chance mutations and contingent situations; culture is pluralist, home to many voices at different pitches and qualities; culture is democracy, a practical art of associated living subject to our own actions and decisions. It was once said that there is special providence for drunkards, fools, and the United States of America. It is easy to mistake the complex machinations of a free society for providence, as many of our ancestors did for weather. No, it is up to us to make our next steps, and to hope they lead somewhere with different, better problems.

“The greatness of America lies not in being more enlightened than any other nation, but rather in her ability to repair her faults.” — Alexi de Tocqueville, Democracy in America

Pragmatism

The review, at this point, requires a conclusion. It has gone on long enough. I fear, though, that I have not done this book justice in its texture and specificity — Nathaniel St. John Green, Henry Abbott, and Louis Agassiz are but a few odd shards of the kaleidoscopic cast of minor characters which illuminate this book and its world, and I know I did not even do them justice. Louis Menand’s writing is clear and compelling, and to appreciate the way he weaves all the tangled social lives of his subjects would double the length of this review without making a dent. The care with which he characterizes the fathers, the mentors, and the oddballs who illuminate The Metaphysical Club give credit to his experience as a professor of English, rather than merely history or philosophy.

The threads I am not able to include here are numerous — the familial influences on James and Holmes, the incredible story of Jane Addams, the various tales of Civil War courage and cowardice, the racial anthropology of the pre-Darwinian biologists, the various projects of John Dewey, the cultural pluralisms of (among others) Alain LeRoy Locke and Horace Kallen, and so much more.

Many of my favorite book reviews in this contest have some critical edge to them. With this book, I truly struggle. It’s a masterful work of intellectual history.

Pragmatism is both a product of modernity and a response to it. Pragmatism refuses to reify beliefs — it has seen too many; pragmatism allows for the proliferation of beliefs — it has yet to see enough. Pragmatism is a progressive, provisional philosophy. It, like the ideas that inspired it, does not bend under the strain of variance and exceptions, but actually anticipates them and, as a theory, is strengthened by them.

Pragmatism’s greatest failure, it seems to me, is its inability to grapple with moral questions. This shows up in various ways: Chauncey’s nihilism is the most obvious. In most cases, it seems, an unreflective utilitarianism takes over the place of any attempt at a pragmatist morality — I would have no issue with utilitarianism honestly come by, but no pragmatist argues for a pragmatic utilitarianism. Pragmatism, presumably due to the context of its time, was largely quiet on the question of morality. This was supposed to help with modern peace. This was the theory of modernity before World War II.

Holmes relates the story of Henry Abbott, the perfect functionary who did his duty despite disagreeing with the cause. Henry Abbott’s largest complaints were never about the cause, but about getting passed over for promotions; his greatest motivations were never about functionary duty, but about the feeling of his own skill. I wonder, though, how Holmes would have reacted to Eichmann. When does the functionary stop and the person begin? Perhaps you bite that bullet, and you say yes, it is not the citizen’s responsibility to check the leader; an orderly society is worth a Holocaust. I don’t like the look of that bullet. Smells like almonds.

There are reasons why Americans planted tolerance on transcendental grounds in the wake of World War II, and it is not only because of propaganda — it is also because, speaking pragmatically, creating a social taboo in addition to a political one (can you have one without the other, really?) means that it might just be that much harder for an American Hitler to find his American Eichmann. I don’t want to sound too Panglossian, but should not a pragmatist at least look at the purpose of the depragmaticization of tolerance?

The best argument I can give is that the philosophy of pragmatism itself is a moral practice. The greatest violence its founders experienced occurred due to what they believed was moral abstraction gone mad. A supporter of the union army in the 1870s and 80s watched abolitionism send the country to war, and maybe — like Holmes — even supported it. They freed the slaves, and the country was torn, and now, looking at the freedmen’s position, they’re going to have to be freed all over again. Four years of brothers in the same national project butchering one another and nothing has changed. Holmes bought the idea and then saw where such projects led: Antietam. Piles of bodies to produce a new euphemism for slavery. Abolitionism’s antipolitics was perhaps the most convincing argument for hard-headed democracy that exists.

Of course, there are moral problems other than war, but modern war was unprecedented in 1861. Is it not reasonable, perhaps, that some of those closest to its advent — Wright and Holmes — wanted this badly for it to be forsworn? Perhaps, but it remains a weakness of the philosophy. As Menand puts it, pragmatism can explain everything about beliefs except why one would be willing to die for one.

And that is fine. Ideas are created by people for reasons. They never mirror reality; they are as provisional as habits are. Even the most exact thrust requires a riposte, and it is only when a strike is never returned that a fencer leaves the arena. Our ideas will never be perfect because ideas are made to help us with our problems, and the world — our problems — never stays still for long enough in order to be perfected in our minds. As provisional as beliefs are, so social as thinkers are we. Beliefs may need to be changed, but we do not gain from cutting ourselves off from the ideas of the past. In doing so, we would merely shrink our pool of available tools.

There are times when reading The Metaphysical Club that its America seems hopelessly alien, other times when it seems startlingly present. I hope that no Civil War-like conclusion awaits us, but if nothing else, this book is a look at one way America built itself back up out of the rubble of its previous societal structure: through its ideas. America is something of a revolutionary land — but it can also be a deeply practical one as well. This is the country of both Thomas Paine and Alexander Hamilton, and each have their time. I, for one, throw my bag in with Hamilton. But not unreservedly.

And that, if I may say so myself, is the way of an American Pragmatist.

The French have no philosophy of their own invention. The primary function of French philosophy is to make German philosophy less rigorous and more sexy. This assertion is roughly 30% facetious.

Much fun in the book comes from its careful descriptions of ‘Brahmin’ society in Boston and its tight-knit, almost clannish qualities.

Joke. My time in undergraduate economics has embittered me somewhat.

Cf. in any reasonable review of The Dawn of Everything.

Why is this important? Well, it seems to me that the eaerly adopters of new social values generally come from the left.

An interesting pattern is that the sort of semi-religious idealistic radical moralism present in abolitionism is also the motivating strand in the Civil Rights Movement and our current battles over Wokeness (or Social Justice Leftism or whatever you want to call it). Meanwhile, the Progressive Era of the early 20th century, which did much to improve the conditions of Americans economically, did so at the expense of support for racial minorities.