The New Project

The first post I wrote on this blog was an abortive attempt at explaining Kant’s moral theory.

It’s not half-bad, for what it was trying to be. However, I never returned to it. Haunting any project explaining Kant’s philosophy are the million million spectral minds just as sharp (or sharper) than your own, with words just as clear (or clearer) than those you can summon. The productions of world-historical intellects like Kant are not exactly unbothered land.

The history of Western philosophy is often divided into four eras: the Ancients (i.e. Greeks), which we sometimes divide between pre-socratic and post-socratic; the Scholastics, who tend to get more attention from theologians than philosophers because they’re very religious and are mostly trying to reconcile the Ancients with Christianity; the Early Modern philosophers, who were trying to deal with Descartes’s doubts concerning knowledge and reality, and split into the two camps of rationalists and empiricists; and the Post-Kantian philosophers, who. . . well, that’s us.

Immanuel Kant’s philosophy kicked off the last 250-odd years of philosophical inquiry. It’s pretty important. So a lot of people have written about it. Some of them might even have been as smart as Kant himself!

The trouble with Kant’s primary writings on the matter, necessary though they were to the general endeavor, is that they are famously abstruse. From what we know about Kant’s life and, indeed, his other writings, he wasn’t a particularly bad writer. By all accounts, he was an able lecturer well-regarded for his clarity and wit. He hosted dinner parties for European luminaries which were well-attended and well-appreciated. It is not a lack of general linguistic facility that caused such sentences as (allow me to open to a random page of the Critique of Pure Reason) “[i]f the objective reality of a concept cannot be in any way known, while yet the concept contains no contradiction and also at the same time is connected with other modes of knowledge that involve given concepts which it serves to limit, I entitle that concept problematic.”

That one is actually not that bad. It’s quite short as far as Kant’s sentences go. However, it gives a sense of the difficulty Kant is working with: he is trying to work at an incredible level of abstraction, and while at that level make fundamental conceptual innovations. If nothing else, this difficulty functions as a full employment scheme for Kant scholars.

And there are many, many brilliant Kant scholars.

What could I hope to add? Beyond, of course, the particular constraints and formalisms of a blog series, my sparkling wit, and my good hair.

Kant set out the philosophy for which he is famous1 mostly within his three “Critiques” written in the 1780s: the Critique of Pure Reason (“CPR,” the First Critique), the Critique of Practical Reason (“CPrR,” the Second Critique), and the Critique of the Power of Judgment (“CPJ,” the Third Critique). His Groundwork for the Metaphysics of Morals (“the Groundwork”) is also usually included in this group as setting out the fundamentals of his ethical theory.2

While Kant faced many difficulties creating and arguing for and explaining his theory, I think one of the major ones was the fact that three activities got all jumbled up throughout the whole process: creating, arguing, and explaining. Kant didn’t know where exactly he would end up when he started (which makes the extent to which it all hangs together even more impressive), even with his “silent decade” of preparation. Furthermore, he had to prove his system as he was explaining it. I think this lattermost difficulty is underrated. No one was going to read a 100-page explainer on an incomplete and unproven philosophical system written by a new German philosophy professor who had not published in 10 years, yet without such an explainer, this notoriously complex and difficult system is even harder to understand.

Kant had to explain his system from the bottom-up. His pages are filled with definitions of newly-wrought jargon interspersed with detailed argumentation and references which only become clear put in the context of arguments found in later chapters. There is a perennial tension between the webbed nature of knowledge and the linear nature of language and learning. Kant throws you into his system, introducing terms as they are required in a barrage of arguments, each argument helping affix some small piece of his system to the board, but without its position or relations immediately (or even within the next 100 pages) clear. I know of few philosophers who are so greatly improved by a second reading as Kant. The first 30 pages of Kant you read, no matter which 30 pages they are, will almost certainly be the worst 30 pages of Kant you ever read.

So, I have decided that this is will be my contribution to the Kantian literature: I am going to begin by not proving anything. No attempts will be made, at first, to show whether the system Kant has built has any relationship to reality. I will illustrate the terms with examples, but I will not attempt to prove their necessary or fundamental place in our cognition. Instead, I will be banking on Kant’s name and import to provide reason for learning about the system per se disconnected from its justifications. Once that is more or less in place, we can explore some justifications and implications.

First, I will paint you a picture, and only then will I show why you might believe that it is actually a window.

An Aside: Why This Is New

I have a few theories as to why this particular manner of explaining Kant has not, to my knowledge, been seriously attempted.

The first theory is that modern Kant scholars, especially if they are writing for a general audience, seem a bit embarrassed about the ambition and nature of Kant’s system. All reasonable philosophers know that the only numbers that should show up in philosophy are 0, 1, 2, and infinity. And usually 2 becomes either 3 or 1.3 Ending up with a 3 is something of a faux pas, so really the safe numbers are 0, 1, and infinity. But Kant has 12 categories, organized into four groups of three! If you see Kant’s graph of the Categories and you don’t at least give a bit of a double-take, then you may be too gullible for this line of work.

Because of this reticence, most discussions of Kant either downplay the plumbing of the overall system or recapitulate Kant’s troublesome path in more modern language, going argument by argument and introducing the system when it is necessary. It might hook more people to begin with the arguments of space and time as forms of intuition and the bases of geometry and arithmetic, or the timeless philosophical quagmires of God, freedom, and the beginning of the world. I wouldn’t know—I’m not particularly good at hooking, it seems.

The second, related, theory is that I am not sure how much Kant scholars have actually bought into the system. I’m not even sure how much I buy into it! So, if you yourself are uneasy about the details of Kant’s overall system, you may be less likely to start with it. It might seem like starting with the system is a better way to turn new readers off than enlighten them. I think this is misguided, for the reasons discussed above.

The third theory is that I just haven’t read enough Kant explainers, and there are people who have done this but I just haven’t read them. Now, I haven’t read many Kant explainers because you actually only need one introduction to Kant’s system, and he wrote it for you himself. If you need someone else’s, that sounds like a skill issue to me. But I don’t think this (somewhat facetious) theory is correct. Introductions to Kant’s thinking are organized almost without fail by subject matter. They have chapters focused on his metaphysics and then later his ethics. They have chapters discussing the transcendental deduction and the antinomies. They have chapters giving the historical and philosophical context of his books. They do not have chapters just filling out the scaffolding of Kant’s particular system. I want to set out the scaffolding.

But first, some methodological preparation.

The Kantian Mind

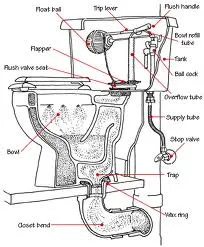

Do you know how a toilet works? On a mechanical level, I mean. Can you write out each step of the process whereby pulling a handle causes water to be flushed out of the bowl and new, clean water flushed in? If you think you can, I invite you to write it out in plain English. No jargon or handwaves, just getting to brass tacks about how dirty water go out and how new water come in. No going into your bathroom and opening up your toilet, either. Make a diagram, perhaps. Explain every mechanism.

Can you do it? Try it. Wait a second before scrolling down and try it. Don’t assume you can if you tried. Actually do it.

Welcome to the illusion of explanatory depth. Most people have never cracked open a toilet and set to work. And even if they had, it was likely under the direction of a YouTube video prescribing a series of discrete steps to solve a discrete problem, not an excursus on toilet mechanics; the knowledge was functional, not systematic. I know you’re all begging to know, so here’s a diagram of a toilet:

Now, let’s try this again: how do our minds work? Obviously this time I can’t stop you from using the object of our inquiry this time, but unlike the toilet, there is no way to pop open the lid and check on the mechanisms. We can look at the brain, but I want to know about the mind, by which I mean our experience: I don’t experience synapses firing; I experience colors and shapes and alteration and thoughts and language and feelings and the slightly-slick plastic of my laptop keyboard. I expect my mind to have correlations to my brain, but if you asked me how I felt and I said things were going haywire in my cerebellum, I expect that you would be a bit nonplussed. So bear with me: how do our minds work?

When we consider the structure of our own minds, we don’t get a neat spatial diagram like the toilet above. There is no “reasoning” button hooked up to an “intuition” circuit flowing through various emotional and conceptual switchboards. The mind is what experiences things in time and space, but we can’t look at it itself in that very time and space. We can see a brain and look for correlations, but, as above, there is an important distinction.4 In this sense, we are unable to turn our gaze or attention back into our minds: the mind is the thing which is doing the gazing and attending.

However, even when you can’t peer into the mechanics, you can say things of the form “I experience X, so therefore there must be some faculty which has the power to have X happen.” For the toilet, we can say, “for the toilet to be able to function as it does, it requires something that refills the bowl once it is emptied.” And we might call that the faculty of refilling. A camera attempting to map its own functions might say it has a faculty of reception, a faculty of capturing, and a faculty of retaining.

As we begin to consider Kant’s map of the mind, keep in mind this structure. We will be talking a lot about various faculties of the mind and how they work. When we call something a faculty of the mind, what we are saying is that there are some things we are able to do with our minds and therefore the mind must have the capacity to do those things. Kant grouped various activities of the mind into faculties for the purposes of interrogating the common operative principles of those activities, and he did certainly believe that these groupings meant something. However, we should not hypostatize or reify these groupings more than we absolutely must. There is an important sense in which the mind is one thing, and that unity will be troublesome if we think of it as a bunch of faculties connected by a series of tubes.

He is also known as an early proposer of the nebular hypothesis in astronomy and the first person to articulate what has become known as democratic peace theory. Smart guy.

The Groundwork is, I believe, read more widely than the Second Critique, although the Second Critique was intended by Kant to be his more authoritative work on ethics.

Thank you Elijah for this note.

Additionally, consider that it is the mind which experiences the brain. We might use that experience of the brain as a helpful tool, but it cannot ground our understanding of the mind because first you have to have an idea of what a concept is before you can say that certain neurological processes reflect conceptual formation.

![Kant's Morals: Rights, Catera[gorical], Action! [1]](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!IP7Z!,w_140,h_140,c_fill,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep,g_auto/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2Feebfa6c5-e7be-460d-9438-79bd1546d782_2000x1500.jpeg)