Kant's Morals: Rights, Catera[gorical], Action! [1]

The start of a series on the moral system of Immanuel Kant

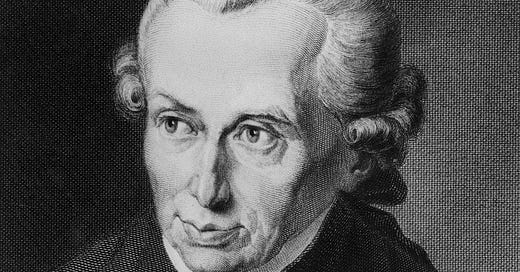

Much ado about Kant

Immanuel Kant is one of, if not the, most important philosophers in the Western tradition. He is so important that his name only arguably comes after Plato, Aristotle, and Descartes in terms of philosophical influence. He is so important that of the three main categories of moral theories (consequentialism, virtue ethics, and deontology), his work largely defines one of them (deontology). He is so important, in fact, that this (his work on deontology) wasn’t his most consequential contribution.1 It was, to be clear, incredibly influential; it’s simply that his work on metaphysics and epistemology is often seen as founding a new era in philosophy, which is something of a difficult bar to reach twice in one lifetime — almost, I suppose, by definition.

Deontology is a category of moral theories that takes as its primary concepts duties and rights — the good in this case is grounded on the duties we owe one another and the rights we can be said to have. This is in contrast to consequentialist theories which ground the good in, well, consequences, and virtue ethics theories which do so with (you guessed it) virtues. This post is the first of a planned series on the moral theory of Immanuel Kant. I will be posting these intermittently, each one building on the last. Eventually, we will get to the point of seeing how deontology understood through Kantian eyes compares to consequentialist and virtue ethic theories, and why one might find it more or less convincing. First, though, we need an exposition of Kant’s theory itself.

In this first post I will focus on the term ‘categorical imperative’, often heard when discussing Kant’s morals but less often dissected as a name itself. The series will have a general aim to make incredibly abstract and technical works sensible to those with only some or no experience with philosophy (or Kant’s philosophy in particular). This will not do as a substitute for reading his work directly or a more formal exposition of it,2 but this ought to help orient further reading and provide a backdrop to the less exegetical posts to come (if I need to make points which rely on prior knowledge, I will generally be referring back to prior posts for justification). Orientation, as it happens, is quite important when it comes to Kant. The nature of Kant’s philosophy makes it difficult for him to speak clearly.

A not-so-short aside on the nature of Kant’s philosophy

Kant is a kind of philosopher that has if not gone extinct at least become endangered over the course of the last half century to a century: a system-builder. Philosophers now, if they’re not commentating on prior philosophers, usually expound on particular problems, form theories in specific realms, or coin concepts/problems for the purpose of developing an issue. Rarely, if ever, do you see an attempt at a totalizing system of philosophy, linking all the branches of philosophy and problems therein into one cohesive whole. Kant’s most important works were such an attempt. His three Critiques (of Pure Reason, of Practical Reason, and of the Power of Judgment) each developed his system in the realm of a different branch of philosophy.

In the project of systematization, Kant had to coin terms that are difficult to parse on first reading, but are defined in such a way that each one helps form a web that gets sturdier as one goes along. For this reason, the first twenty pages of Kant that you read will often be bewildering, as he introduces you to his system without defining everything at the start (because to do so would be even less effective). It’s a blitz of terms and convoluted sentences that can overwhelm almost any reader. As a piece of advice to those interested in reading Kant: note your questions and incomprehensions, but don’t get hung up on them. Kant retreads his path again and again as new arguments contextualize old ones, so what is incomprehensible or inscrutable now will (hopefully) take on real meaning later.

This problem is exacerbated by two things. First, Kant is just not a particularly good writer. Some blame Kant for making bad writing acceptable in the philosophical profession — and it is true that his sentences can look like paragraphs, his paragraphs like pages, and his pages like alphabet soup.3 Second, (and here is where Kant deserves some sympathy) Kant is attempting an incredibly difficult undertaking at an incredible level of abstraction. Oftentimes what is most confusing about a Kant passage is not parsing it formally, but connecting it to some actual experience of the world. This gets easier as one gets a better grasp on the central terms and concepts, but it never gets easy.

This is all made somewhat ironic by Kant’s position that what he is doing is not so much creating a moral theory as exposing what “common human reason” already contains, making explicit what our general moral reasoning already had implicit and providing clarity rather than novelty (GW 4:404-4:405).4

Categorically Imperative

So, with the stage somewhat more set, let’s get down to brass tacks (or at least begin gathering the copper and zinc required). Since Kant’s system is so webbed, there are many ways of approaching it. The most widely-read piece of Kant’s moral philosophy is his Groundwork of the Metaphysics of Morals (which was, as the name suggests, a sort of groundwork for his later-published Metaphysics of Morals), the most exhaustive picture of his moral philosophy is probably his Critique of Practical Reason (although my experience with it is sadly minimal), and the first mention of morality in his systematic works comes in his Critique of Pure Reason (which at first was meant to be the Critique, until Kant wrote too much and figured he needed a second).5

However, what is most well-known about Kant’s moral theory is that it is built around a distinct core: the categorical imperative (CI). So, let’s start there and see how Kant makes his way to such a notion. In this post, we’ll see why morality, for Kant, whittles down into something called a ‘categorical imperative’.

What’s in a name?

What differentiates actions from occurrences? My throwing a rock is an action, but a rock falling from a cliff is, philosophically speaking, not. With an action there’s a sense of intention, of a person behind it — of a will. A will, according to Kant, is “the representation of laws” according to which one can act. This differentiates rational beings (so called since reason is required, according to Kant, for deriving actions from laws) from objects and other actors (GW 4:412).6 Frogs, presumably, do not represent laws to themselves.7 Nature acts according to principles (as is the general assumption of science), but it has no capacity to consider those principles. Only a rational being is able to actually cognize about principles and laws — i.e. represent them to itself.

Kant believed that our willing of an action looks (in a rough, linguistic sense) like “in such case X, I will do Y to bring about Z.” This formulation (though generally implicit) is called a maxim.8 Here, X is a condition, Y is a means, and Z is an end. The picture is not so simple that an action only has one condition, one means, and one end — actions often have many conditions that we only might be able to spell out, a complex means that could be conceptualized in several different ways, and serve many ends. This is called, generally, the problem of overdetermination, and will be dealt with in later posts. Nevertheless, that is the rough picture we aim to have in our minds.

Along with willing, reason also includes the capacity for comprehending imperatives. Imperatives are, roughly speaking, ‘oughts’. One might recall that the imperative form of a sentence is a command, and that sense does not entirely change here: “you ought to do this” contains an implicit “do this!” Imperatives, then, have a sort of necessity (a practical necessity). This is not the necessity of formal logic, math, or natural law in that what is a practical necessity can fail to happen, but it is a sort of necessity nonetheless. ‘Oughts’ are clearly a requirement of some sort; otherwise, the concept is nonsensical.

Kant discusses different ways of distinguishing imperatives from one another, but the cut we are looking for is along the line of hypothetical and categorical. Hypothetical imperatives are conditional. As hypotheses are formulated as “if P then Q,” so too are hypothetical imperatives. The imperative “if you want to learn about Kant’s moral theory, then you ought to continue reading this post” is hypothetical — it relies on a condition (in this case, your desire to learn about Kant’s moral theory) for it to have practical necessity. Clearly, hypothetical imperatives exist, but what Kant is interested in proving is that categorical imperatives exist. More specifically, that a categorical imperative exists, and it is morality.

Categoricality and morality

So, let’s consider what the existence of such a categorical imperative would mean. First of all, it would be an imperative: an objective principle meant to command the will (GW 4:413). It would also be categorical, binding the will whenever it acted. It would therefore bind the will no matter what the ends of the will are (this is one way to understand the idea that comes up regularly in Kant that the categorical imperative is an end in itself) (GW 4:414).

A first, intuitive place to for the categorical imperative look might be happiness (or flourishing, good living, well-being, etc.). There does seem to be a sense in which we are categorically trying to be happy. It's the implicit, if not explicit goal of much of what we do! However, there are two reasons this is misguided, one empirical and one conceptual. The empirical reason is that, as many a wise thinker has noted, "the more a cultivated reason engages with the purpose of enjoying life and with happiness, so much the further does a human being stray from true contentment" (GW 4:395).9 In this case, a categorical command to happiness is practically sure to thwart itself; happiness seems almost specially constituted to not be a categorically binding end for our will. But this doesn't work as a conceptual formulation of the problem.

In rational terms, the issue comes from our lacking a "determinate concept of happiness” (GW 4:417-4:418). The particularity, complexity, and empiricality of happiness make it impossible for us to say exactly what will make us happy.10 This means that an imperative which is supposed to command without exception would have no specificity with which to command. Now, this does not mean, per se, that the categorical imperative will have nothing to do with happiness (that it does not will be shown later), but it cannot collapse into counsels for happiness. So does it exist at all?

It is quite clear that morality, generally construed, at least appears to have the character of a categorical imperative — it is an ‘ought’ that relies on no condition for us. If something is the morally right thing to do, then I ought to do it no matter what. The imperative itself is its only condition. All other ‘oughts’ are self-evidently hypothetical — it is only morality that at least appears to practically necessitate action merely by its fact of practically necessitating action. Since only morality even possible has the character if a categorical imperative, if a categorical imperative exists, it will be a moral law.11

So the problem which remains is whether such a categorical imperative actually exists or whether it is always merely a hypothetical imperative dressing itself up as categorical. It might be that morality collapses into prudence and that there is no such thing as a categorical imperative. Kant gives the example that the moral command that one ought not to lie might be a hidden hypothetical imperative — that lies are often found out and if one doesn't want the consequences of being branded a liar, then one ought not lie (GW 4:419). If a CI does exist, then we at least have a lead on what morality is.

[Don’t] get your epistemology out of my morality!

I have so far waited as long as possible to introduce the epistemological terms that Kant brings into his moral theory, but they were always going to sneak their way in somewhere. Kant, being the systematic thinker he was, intimately connected his moral and epistemological theories. It so happens that the categorical nature of a CI means that it is a very particular sort of notion.

For a categorical imperative to be categorical, it must be without presupposition. It therefore cannot be something we learn from experience (i.e. be a posteriori, Latin for ‘from later in time’), as all principles from experience are necessarily conditional on some facts about the world, rather than true by virtue of the nature of our minds. Furthermore, to prove the existence of the categorical imperative means proving the lack of hypothetical imperatives lurking behind it, which is impossible a posteriori, as one cannot prove non-existence of a cause in experience (GW 4:419). So, if a categorical imperative is to be found, it is to be found a priori (Latin for ‘first’). Furthermore, a CI will not be merely analytic, or be true merely by virtue of definition, but synthetic, i.e. the result of two notions held in connection with a third.

The existence of a priori synthetic propositions is something Kant takes up in his first Critique, but the general idea to keep in mind here is that these propositions require an investigation into the nature of our minds and how they constitute experience. Because a priori synthetic propositions have their ground in the constitution of experience by our minds, they are necessarily true because they are part of the grounds of our experience. Now, what does this imply about the possible character of a CI?

“A law as such”

The most important turn in Kant’s Groundwork comes directly from this characterization of a CI as a priori synthetic. Let’s consider what we know about a CI: it contains nothing from experience, it is a law, and it requires all maxims of the will to conform with it. Therefore, so the turn goes, all that remains in the law is its own universality — “the universality of a law as such.” Then there can only be one categorical imperative:

“Act only according to that maxim through which you can at the same time will that it become a universal law” (GW 4:421).

In other words, act lawfully — not in accordance with any particular law, but rather act only under maxims having the character of a law.

Next time on…

Let’s review what was covered in this post. Kant’s webbed system has many entry points, of which I picked the definition of action. This led us to consider that what differentiates action from mere effect is the ability to represent laws to oneself — basically, to consider and produce action conceptually. The form of the imperative is particularly important here as a way of representing a law as practically necessitating an action. In turn, we considered the idea that there could exist an imperative that practically necessitated action unconditionally — this seemed a fertile area to look for morality, as one of morality’s defining features is its unconditional command. For a command to be unconditional, however, it could not be found empirically in the world — rather, it must be a priori. An a priori command, however, could contain no information from the world — it must be entirely formal, in the sense that all it has is the form of law. If an imperative is a law that necessitates willing, then a categorical imperative could only be a law that necessitates willing as law. That is where we arrived.

You may notice here the focus on a few things: the will, law, and necessity. These (and for the lattermost its converse, freedom) are the central concepts of Kant’s morality. Kant saw our minds (and experiences) as being law-governed. In his epistemology, our minds generate principles, connect them to experience through rules, and explain the world in laws.12 Here, in his morality, our minds generate maxims, necessitate our wills through imperatives, and act in accordance with laws. A lack of law is incomprehensible in Kant’s view — and I mean this quite literally, as the way we comprehend things is through laws.

In the next post in this series, I expect to expound on the implications of this strange-seeming formula, how it connects to our commonsense notions of morality, and show that this is not the only face of the categorical imperative.

For reference, in modern philosophy this would be something like if Michael Jordan switched to baseball and then defined the sport for years.

Which you certainly shouldn’t have trouble finding (a general resource for secondary synopses on well-known philosophers is the Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, which can easily be found online but can be dense and a little more jargon-y than what I’m trying to do here).

One more piece of advice on this that has helped me: read the sentences aloud and try out different emphases and rhythms to see if one has a meaning that makes sense. Speaking can help keep more words in mind because it helps you cut the words into their meanings, if that makes sense. There’s probably some psychologically interesting point here about how language was originally spoken, but that’s neither here nor there.

I will mostly be citing from the Groundwork of the Metaphysics of Morals (GW), with a few citations from The Critique of Pure Reason (CPR). This is because the GW remains the go-to place for understanding the foundations of Kant’s moral theory, on which the rest relies, and is therefore of the most interest to philosophers looking for justifications. Although, some of the most interesting (and oftentimes touching) practical moral thoughts come in his other works, like Religion within the Bounds of Mere Reason and Metaphysics of Morals.

He then waited a while, and the thought struck him that he actually needed a third. Then he wrote some more without any reason for a fourth. Then he died. So goes philosophy, I suppose.

This will, like much of the background which informs Kant’s main argument, be taken at face value for now and discussed, justified, or rejected later.

If they do, then France has been perpetrating a moral disaster for years.

These are perhaps not the most rigorous definitions, but they work well enough for our purposes here.

This sentiment can be found from many corners, varying in their directness and level of pithiness. Some favorites of mine:

“Happiness is a butterfly which, when pursued, is always beyond our grasp, but which, if you will sit down quietly, may alight upon you” — Nathaniel Hawthorne

“If only we'd stop trying to be happy we'd have a pretty good time” — Edith Wharton

“Happiness is seldom found by those who seek it, and never by those who seek it for themselves” — F. Emerson Andrews

Those most deterministically-minded among us may say that this is merely a lack of knowledge, and that one day all technique will collapse into prudence, but I am not so sure. The rude complexity of the world and our characters makes the question of happiness not only about what to do in the messy, sprawling situations we often find ourselves in, but also about what will make us in particular happy. The arguments for and against the possibility of reducing all experience and knowledge about the world and ourselves to mechanical explanations that we can then use immediately for our own purposes are complex and not to be gotten into here, but even without going into the strange arena of quantum mechanics where I am even more an amateur than here, one can see how the definition of morality as a categorical imperative leads us inexorably away from happiness — I can have no principle for happiness.

Another way of looking at it is that we are trying to find the moral law, and the moral law must be a categorical imperative, and since only morality can claim categoricality over our actions, the moral law must be the categorical imperative. This is just two different ways of arriving in the same place, but I thought it was worth saying.

I use principle, law, and rule equivalently. I understand that Kant sometimes seems to differentiate between them (putting particular weight on calling something a law, for instance), but this has never struck me as a particularly important distinction, mostly used as a signal for different faculties of the mind or something like that. And the concepts are quite similar.