This is the second post in a series that deals with philosophical problems in personal identity and metaethics. The overall goal is to provide a theory of what it is that people are, exactly. The first post can be found here, and deals with the problem of other minds.

The first post in this series argued that other minds are necessary for action. An important proposition in the main argument of that post was that the subject-self distinction is the philosophically rigorous way to understand personal identity. This was necessary to expand the problem of other minds so we could sharpen its consequences. However, I did not fully justify this proposition at the time. The next two posts of this series will be doing just that.

Generally, we assume that we have some special relationship to ourselves as individuals. This is true in some sense, but philosophical attempts to show that the individual-relation is of a clearly and distinctly different order than other relations we experience are all deeply flawed. The individual-relation is just one more identity relation we have as subjects. This post will introduce the intractable problems with attempting to excavate a clear, well-defined individual from our experience as people. Once it is clear that the individual-other person distinction, as a matter of metaphysics, is not well founded, the next post will deal with what exactly the subject-self-other distinction entails.

The central claim of this post is our inability to resolve philosophical problems with treating the individual as a metaphysically unified, ontologically fundamental, or epistemically privileged part of our experience.1 A malformed understanding of personal identity has led us to ask the wrong questions in many fields. Asking the wrong questions leads us to being more confused once we get our answers.

The distinction among people that we use most commonly is between the individual and other people. We have a sense that “Adam,” who we just saw leave the room and we know from grade school, is one person, and “Betty,” who is right next to us and we just met, is another. And, sure, barring any Mrs. Doubtfire-inspired antics, this is likely true in some sense. However, we may want to know in what sense exactly it is true. What are we denoting as “Adam” in the one case and “Betty” in the other? What identifies the name with a thing in the world, and the other with a different thing in the world? What makes us able to call one thing the same as another thing in a different place or time? Questions like these are questions of identity. When they are about people, they are questions of personal identity.

Philosophers commonly distinguish between qualitative identity and numerical identity. Two things are qualitatively identical when they share all the same qualities; they are numerically identical when they are actually the same thing. Two mice can be qualitatively identical, but they are not numerically identical unless they are actually the same mouse. The essence of the doctrine of the individual is an assertion of a very strong sort of numerical identity of people over time and concordant metaphysical expectations that come with that.

On the metaphysical front, the doctrine of the individual asserts that people have a numerically identical essence which remains with them from the moment they start existing to their death. This then forms the basis for theories of moral responsibility and material ownership. On the ontological front, it asserts that the way we experience our individuality makes for a fundamental difference between the way we exist in relation to ourselves and others. On the epistemological front, it asserts that we have special, privileged access to knowledge about ourselves as individuals which is qualitatively different than that which others can know. These assertions are misguided. The body of this post will discuss questions about identity and attempt to sketch out some problems with the notion of an individual. The conclusion will connect these problems with the specific assertions of the doctrine of the individual and prepare the ground for a new central category of personal identity.

Identity: Ships and the People that Own Them

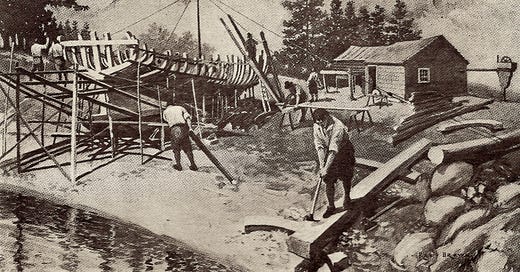

The most famous philosophical framing of numerical identity is in the Ship of Theseus problem: a ship, over years, has every part of itself replaced. Is it still the same ship? If so, what is the same about the ship? If not, when exactly did it become a different ship? In either case, what makes us call the ship the same name or not? Does something as seemingly extraneous as the time it takes to replace every part of the ship matter? Does the problem change if the ship is disassembled and reassembled with the exact same parts?

The situation reveals a common unexamined assumption about the nature of things — that they have some clear essence to which our name of the thing corresponds. Frankly, it doesn’t seem to me that there is a clear, grounded answer to the Ship of Theseus problem. Any attempt either seems capricious or fails to engage fully with the conceptual issue. Identity is a pragmatic consideration — it’s the same ship in some ways, different in others, and we can balance those considerations to say whether we really think of it as still being the same ship. Identity, in this sense, is an abstraction from experience, not a fundamental part of it. We create identity and identities as a way to organize the world, and all such organization is to some extent heuristical, standing in for more granular information.

For a moment, we can take the point of view of Theseus’s brother, who last saw the ship decades ago. Now, not only has each part of the ship been replaced, but 25 years ago, its sail was updated to a newer design and cloth, as Theseus’s travels earned him enough money to upgrade. Also, a couple of years after that, a hole was blown in the starboard hull of the ship that threatened to take it down. In their next harbor, they repaired the hull, but in a different sort of wood. Now, a section of the front (sternward?) starboard hull is a different color, forcing them to repaint a section of the hull and now sometimes creaks against the rest of the ship. 15 years ago, the captain’s quarters were demolished in a fight, and they were rebuilt in a more fortified area of the ship, while some equipment now lives in Theseus’s old room. Over time, more and more of Theseus’s crew has been replaced, as older members retired and new ones came in. Then, 6 years ago, Theseus decided he had gotten too old for adventuring, and refitted his ship to be a merchant vessel. This involved demolishing the brig and some arms storage areas and turning them into general goods storage. To complete the change, Theseus took down his old flags and put in new ones. Finally, just a year or two ago, Theseus himself sold the ship and came back home to help his brother with the farm. His brother heard great stories of Theseus’s seafaring adventures. One day, a painting arrived in the mail. Some of the crew that Theseus had left commissioned a painting of their most recent arrival in port. Theseus shows it to his brother, glowing, his eyes screaming “look at my ship! See its maritime beauty!” The brother, though, is confused — that’s not Theseus’s ship. He’s never seen it before in his life. But of course, in a sense, it is! Theseus certainly has reason to believe it is. It’s so similar to the ship he was just on but a couple of years ago.

Theseus calls the ship the same ship because it’s useful — he owned it, his crew runs it, similar floorboards creak as the last time he saw it, the mast unfurls the same way as the last time it was out, the captain’s lodging is in the same place, etc. But for Theseus’s brother, things are very different — the color’s all wrong, he doesn’t recognize anyone in the picture, the mast looks different, there aren’t even any cannons poking out the side anymore! All qualities change, but they are generally sturdy enough that it makes sense for some to continue calling ships the same name. So do we come to the conclusion that numerical identity is a merely heuristical determination? Is there any consequence, philosophical or practical, that saying the ship is the same or not the same would entail, assuming the agreement on every other fact about it? What is this quality of ‘numerical identity’, ceteris paribus, meant to entail?

Numerical Identity as Ownership

Numerical identity is a relationship across time: “this is the same thing that was.” The important question for us is specifically what consequences numerical identity has beyond this assumed level of qualitative identity.

Numerical identity in itself becomes consequential when we infer a relationship across time due to that numerical identity: “Theseus relates to this in such a way because this is what that was (and Theseus is what Theseus was).” There are very few relationships that are meant to persist across time strictly and solely due to numerical identity. In fact, I will argue that there are two: debt and ownership.2 In fact, insofar as debt is something you own, it is really one: ownership.3 Ownership, in this sense, is closely related to responsibility. We might even say that responsibility is ownership translated from questions about identity to questions about ethics — the same phenomenon in a different theoretical context. This is why questions of numerical identity specifically only gain purchase when they begin to relate to persons. Ownership is a relation of an agent to another thing — without an agent, ownership as a concept cannot apply.

Ownership relations are incredibly important to us. Therefore, we may spend a lot of time building customs and traditions and laws as well as interpretations of those customs and traditions and laws in order to guide us on what exactly constitutes numerical identity, and when ownership relations may need to be broken. It is generally accepted that there are pragmatic and ethical considerations here as well as the ontological and metaphysical ones.4 Underwriting the legitimacy of this system is the unspoken premise that numerical identity implies the retaining of ownership relations, ceteris paribus. In many cases, though, we are willing to admit quite clearly that the system itself is about serving social ends.

Where this willingness usually stops, and where the real target of this post is found, is when we start talking about the identity of people. Because, after all, all of the problems for Theseus’s ship also are problems for Theseus. Theseus, being on the sea for 25 years, could come back unrecognizable to his brother — perhaps not having every single part of himself replaced, but perhaps he started smoking tobacco soon after his first voyage. Maybe that has given him a raspy voice. His skin surely would darken with years under the ocean sun, and perhaps his hair bleach as well (if it has not gone gray entirely). Years of command might make him world-weary where before he enjoyed a boyish enthusiasm. Is Theseus the same person that he was 25 years ago? Perhaps the answer is a combination of yes and no, similar to the ship itself. This is a very important question, though, because a strict relation of ownership towards our pasts is a fundamental proposition in our metaphysical grounding of individual-based punishment and ownership.5

The doctrine of the individual is what I call the attempt to ground, in the metaphysical category of the individual, a particular social, ethical, and legal organization of ownership and responsibility. It is the attempt to answer the question of ownership and responsibility metaphysically: to say that the ship is owned by the individual Theseus, who remains an essential, numerically identical individual throughout his life, and therefore retains his side of the ownership relation totally. Just like the ship, Theseus’s actions are also “owned” by Theseus, and he retains “ownership” (responsibility) over all of his actions throughout his life. My argument in this post intends to dispel any metaphysical grounding of ownership relations through the numerical identity of persons. The individualist mode of creating and systematizing ownership relations is not philosophically necessary, but rather must be chosen.

Personal Identity: Whose Memory? What Continuity? Which Mind?

The question of Theseus’s identity, it is argued, is essentially different than the question of the ship’s. The disanalogy between the two is to be found in the mind. The mind has two qualities which the ship does not: continuous experience and memory. These two form the core of an intuition that the mind holds a metaphysical throughline across time, and therefore grounds a real numerical identity. If every quality about “Adam” changed, could he still be “Adam” in some sense, as long as there was some memory- or contintuity-based link? Even if Adam’s mind was in Betty’s body, even if Adam started acting as Betty would, even if Adam was made up of entirely different matter than before, a relatively reasonable argument goes that it is possible that Adam is still Adam if the same mind is there. Here, the mind is a supposed unobservable font of experience which we identify across time as being Adam.6 We can never observe Adam’s mind, but the argument goes that if Adam’s mind is there, then that’s Adam.

Memory and continuity are argued to provide the mind’s metaphysical unity across time that all other things lack, and thereby ground the doctrine of the individual. Memory is proposed as a faculty of the mind which allows the mind to confirm where it once was.7 Continuity is proposed as a fact of experience which shows that the mind remains the same — continuous — throughout experience. Let us consider each of these in turn.

Memory: Not a Window, but a History

At this point, some arguments against the doctrine of the individual take a flight of fancy into science-fiction scenarios including mad scientists, teletransportation,8 implanted memories, and so on. None of this, it seems to me, is necessary. All that is necessary is to actually experience what memory is like and what continuity actually consists in. Consider a conversation:

Adam: “This is exactly like that time you messed up ordering pizza and instead of getting us 5 slices, you got us 5 pies!”

Betty: “I did that? When?”

Adam: “Don’t you remember? It must have been when we were in high school, because we were at that cheap spot like three blocks from the library.”

Betty: “Oh yeah! I remember that place. I think the story is ringing some bells, too… Did I have to go talk to the manager or something? I think I remember that.”

Adam: “No, I’m pretty sure we just paid and had a bunch of extra pizza. Wait, was it you or Charles I was with? Because I think I remember separately you had an issue with an order and had to talk to the manager.”

Charles: (happening to pass by) “Oh hey Adam, Betty. What’s up?”

Adam: “Just the man we wanted to see. Was it you or Betty who accidentally ordered 5 pizzas instead of 5 slices at that spot — Geronimo’s! That’s the name — when we were in high school?”

Charles: “Oh, man, that sounds like something I would do. Wait! Oh, for sure that was me. I remember doing that, and then that wiped out my whole allowance for a little while. I had to tell my parents about it and they were pissed — you know how my dad is with wasting money. They were happy about the leftovers, though.”

A few notes here. First, my fiction writing is still very much a work in progress. Second, I want to point out that the way that Adam, Betty, and Charles talk about their memories is not in any way similar to the way they would talk about the experience they are currently having. In fact, it’s more similar to the way one would talk about a fact or story. And that is, to an approximation, the claim of this section: memory is in the same category of experience as knowledge, not sensation. That is to say, the previous distinction we made between memories of experiences and memories of facts or knowledge is not a fundamental one; it cannot ground a metaphysical claim. The central mistake that the doctrine of the individual makes is thinking of memory as a window into the past. It is not. It is better thought of as an oral history.

Nothing out of the ordinary happened in Adam, Betty, and Charles’s conversation. Adam misremembered something, Betty had a vague impression that attempted to fit itself to Adam’s misremembering, and Charles corrected them by confirming one memory through its coherence with a web of others. This lack of surety, the coherentist reasoning, and the intersubjectivity of the effort all speak to major faults with memory as a supposed unifier. These are, quite simply, mistakes and corrections you make about knowledge. For memory to have some special significance, it needs to connect us with our pasts at least better than knowledge connects us with the world;

Memory simply is a sort of knowledge, more akin in type to knowledge of a story than experience per se. One cannot doubt the qualia one is experiencing; one can doubt what its implications are (“sure, I see a haze of blue across the desert, but does that mean that when I arrive there will be an oasis or is will this have been a mirage?”), but one cannot doubt that one is experiencing it (“I see a haze of blue across the desert”). This can be difficult to see because the way we explain and conceptualize what we are experiencing in itself contains theory — the use of the word “desert” above implies certain expectations already. Nonetheless, we cannot doubt the qualia itself; it is exactly as it is. In contrast, memory is a game of vague impressions, second-guessing, and furrowing one’s brow in concentration to get at what exactly one remembers about a situation. It is a common experience to begin to fit one’s memories to someone else’s suggestion if it seems plausible. Memory is a story we roughly know, which has attached to it the added piece of knowledge that it was ‘learned’ through a particular sort of process (i.e. at one point, it was experienced). If memory is the glue that ties the present to its past, then there needs to be some way that it is different than the glue that ties the present to everything one knows or thinks or can imagine. And there is no such way.

One may still feel a sense that memory is special in that it seems to be real in a way that free-floating facts and knowledge is not. That is misguided. Memory is information about the past. Once that time is gone, it lives on merely as information, same in our ability to recall it (or not recall it, or recall it erroneously, or partially recall it) as any other piece of information we have. Once an experience is a memory, it is no longer experience, but merely one proposed class of information. Calling something a “memory” is a stand-in for some proposed relationships between this information and the world: that it came from a certain source, is about a certain being, and relates to a certain time. Things have happened to me which I cannot imagine half as well as I can imagine the city of Genua from Terry Pratchett’s Discworld series.

It might be argued that memory is a special case because all the information we have came from memory. Memory is the basis of all learning, of course. Yet our experience of all information is not of it as memory. And what we actually experience is what is dispositive. We do not, Slumdog Millionaire-style send ourselves into a flashback whenever we need to recall information. Rather, the information is there, often bereft of a source, sometimes wrong, but never with the facticity of sensation.

Memory is not a window into the past. Our minds are not tape recorders. It is not the still-living ghost of another time that you summon before your eyes. It is an oral history. It is a set of impressions and facts that you retell and reconstruct each time it is called forth. Memories can haunt us, it can feel exactly like we are ‘back there’, but they are reconstructions, not the past itself. The past does not exist, and memory cannot bring us there. Memories have no more inherent epistemic or metaphysical privilege than any other piece of knowledge. And without such privilege, they cannot tie together a metaphysical whole.

Continuity: Patch-ups and Paralogisms

Any attempt to justify a metaphysical entity based on memory will have to deal with the fact that we often take on others’ memories, construct false memories, and have the vast majority of our life fade into unremembered obscurity. The proposed solution to this issue is to propose a chain of memory, whereby my connection to all past instances of myself as an individual is given by my being able to remember a moment before now, in which I could have remembered a moment before then, and so on throughout my life. Really, this is more a cover for using continuity to justify the doctrine of the individual rather than an actual attempt to use memory. A chain of memory is no sort of relation that speaks to experience; it smacks of post hoc rationalization — we feel that the individual is a thing which exists, so we patch up the memory theory through the use of a chain. Nonetheless, let us entertain, for a moment, the theory on its own terms.

A few problems arise. For one, I did not, a few moments ago, actually remember the moments before then. That would have required a thought. Instead, I was typing something new out on this blogpost. The ‘could’ does not provide a psychological connection, but merely the counterfactuality of one. But let us put that aside and entertain even the notion that the capacity to remember is enough. First, there is the problem of sleep. We don’t remember the moments immediately before we go to sleep, and it does not seem clear that there are no moments where we do remember those moments. Are we different people in those moments? Second, there is the problem of false memories. When I misremember, am I creating a new, fictional individual that I am the same person as? That is nonsensical.9 Third, there is the problem of amnesia. If I lose all memories before a certain moment, am I a different person than before that moment, since the chain of memory has been broken? It does not seem like it should be an all-or-nothing determination. Fourth, there is the problem of partial amnesia. If I suffer a head injury and am knocked out while losing my memory from the hours before the experience, was I a different person for those hours than I was during my whole life previously and afterwards? Surely not.

There are more cases where this theory breaks down. You could mix in diseases of degenerative memory loss, for one, or blacking out from alcohol. These, though, should be enough to point out that continuity in memory is not infallible. In fact, it is deeply fallible. Even a basic reality of life such as sleep forces problems, and slightly more exotic considerations make it completely break down. Of course, all of these assume that the argument from a chain of memories is really about memory. It is not. It is instead founded on the continuity of experience. The theory is a patch-up of a failed mode of explaining individuals that plays on a nugget of truth: our experience, as a forward-looking phenomenon, is continuous.

The doctrine of the individual’s strongest asset is this continuity of our experience. The thought goes that because our experience keeps going continuously, you should be able to tie together this continuity until you have a whole, almost like a proof by induction, and that this continuity shows that there could be no change in the mind’s numerical identity over time.

To be clear, experience could only be continuous — a break in experience is fundamentally, categorically, ontologically impossible. A break in experience over time would require a period of time in which one is not experiencing. However, if one is not experiencing, one does not experience! One would only being experiencing again when experience once again began. Put plainly, an unconscious person does not experience unconsciousness. They experience the time before being knocked unconscious, and then the time after being knocked unconscious. The ‘break in experience’ is merely a sharp, discrete change in sensation. The real problem with the argument from continuity is that, well, what is it exactly that the continuity of experience shows? The Ship of Theseus also existed continuously — why does continuous experiencing have the special quality of making the mind numerically identical while the Ship of Theseus’s continuous existing does not?

Kant’s Paralogisms of the Soul

Look, I wasn’t going to write a whole series of philosophy posts without an assist from my main man on the scene, Immanuel Kant. With a lot of his theory (especially the actual positive aspects where he’s building out his system), there are quibbles and revisions I like to make here and there, clarifications I think help the thing stand up a little better on its own two feet, and so on. However, here is one of the areas where Kant is at his best: showing the way that the metaphysical assumptions of his time are based not in any real sort of experience or knowledge but rather in a fanciful flight of reason outside of its purview. And sure, I could probably figure out a different way to skin this particular cat, but why do that when the Continental King of Königsberg himself put it best?

Wake Me from my Paralogistic Slumber

As always, philosophical confusions about the mind begin with the fact that we do not experience it. The mind, as an object of our thought, is merely a necessary correlate of experience: I have experience; there must be something (a mind) doing the experiencing; therefore I have a mind. The mind is the hole in the world from which we are pointed outwards. We must posit it, but it can never be a part of our experience. The mind is the “vehicle of all concepts,” but is a “simple, in itself completely empty” representation (Critique of Pure Reason, Kant B399; B404). “Through this I or he or it (the thing) which thinks, nothing further is represented than a transcendental subject of the thoughts = X” (Kant B404). Rather than the mind being a picture, it is the camera. And the paralogisms are our attempts to apply to this camera all these concepts that pertain to pictures. That is the table of 4 parts above — we think of the mind as a simple, thinking substance which relates to possible external objects (the table says soul rather than mind because it was written before philosophers decided that believing in an unchanging, immortal soul was altogether silly, while believing in a consistent, individual mind was simply common sense).

The Soul Is Not Simple — Or, Rather, We Cannot Know the Soul to Be Simple — Or, Rather, the Concept of “Simple” Could Not Apply to the Soul

Something is simple which cannot be regarded as the confluence of multiple things or their actions — the opposite of simple is composite. There is a clear reason why we would assume the mind to be simple: it quite obviously could not be thought of as the confluence of multiple things if we do not have access to it in experience. What multiple things could it be made up of? Furthermore, thought can’t be composite in an important way — a group of people each thinking one word of a verse does not thereby create a thought of the verse. Rather, a thought must be tied together by the unity of a single mind (Kant A352). But, as Kant importantly points out, it is entirely coherent to have a composite unity. The mind itself functions by aggregating concepts and sensations. Even more strongly, a unified output can come from a composite thing. A camera can have many constituent parts while creating a unified picture.

All of this talk itself is moot, though, since “simple” is a concept that we use to describe things we have experience of. The mind is something outside of experience. There is no reason to believe that the same concepts could even be used for that which forms our experience as that which we actually experience.

The Less Harmful — but Still Misguided — Type of Substance Abuse

There is a similar temptation to think of the mind as a substance which persists while its ‘accidents’ (ye-olde-philosophy-speak for the momentary determinations of a subsisting thing) change. The mind would be this subsistent object while thoughts and experiences come and go. No object in experience can be deemed persistent before we find it persistent. What makes us think that the mind is persistent? Because we keep experiencing? As mentioned before, if we stop experiencing, we don’t experience that. Our minds could wink in and out of existence constantly, and we would keep experiencing continuously. Experience is not interrupted by lack of experience. Yet the mind’s substantiality would be.

Continuity, Simplicity, Substantiality

If the mind is a continuous simple substance, it must persist in a numerically identical manner for as long as it exists. For if it is substance, then it persists over time in some fashion. If it is continuous, then something must be retained in its continuity. If it is simple, then if anything about it changes, then the whole changes. Therefore, continuity implies numerical identity for simple substances. And numerical identity could only be justified by a simple substance — the ship, personal qualities, all of these are composites of many things, and so can be continuous in time while changing. It is the mind’s supposed simplicity which supports the argued necessity of its numerical identity. But we cannot say the mind is simple, and so its continuity implies nothing of the sort. All time is continuous, and nothing has numerical identity.

The Individual Is Not…

The doctrine of the individual requires an identical person across time. Unable to find it on the surface, it proposes its existence in the mind. It does so through backwards-looking memory and forwards-looking continuity. But memory is fallible and unprivileged, while continuity lacks consequence. The pseudo-psychological theory of these arguments would say that we began with an idea of numerical identity because it was useful for qualitative identity and organizing ownership relations, and then we mistook our idea of numerical identity for something fundamental to the world, experience, and knowledge. The whole doctrine of the individual is a fateful example of hypostasis — the practice of treating something abstract as a concrete reality.

Now, let’s return to the central assertions of the doctrine of the individual and apply the problems we have discussed here directly to them.

…Epistemological

The doctrine of the individual asserts that we have some sort of privileged epistemological relationship to ourselves as individuals. That is, that we can know things about ourselves that no one else can know or find out. The evidence for this is generally some combination of knowing what we are currently experiencing/feeling/thinking and knowing our personal histories (i.e. our memories).

The first of these is actually a fact about the subject, as we will discuss in a later post — our full present experience is something that is truly separate and impossible to extend beyond our own mind, but that can be cordoned off from the problems of the individual, which come from attempting to extend the privileged position of the subject across an individual’s life. However, even this has problems — while only we can experience the fullness of our own experience, other people can still point out facts about our own experience that we do not consciously recognize — i.e. that we do not know. They can cause us to recognize an aspect of our experience even as personal as the fact that we seem to be having a good time. A very plausible interaction is a distraught friend becoming engrossed in some game or project and being told, “hey, you’re smiling. You’re happy, you know? It’s good to see,” and them being surprised by that fact, not having quite recognized it. So privileged access to ‘knowledge’ is not quite right — we have a different dataset of ourselves than everyone else, and that can lead to different areas of expertise about ourselves, but not necessarily a strictly dominant level of expertise. There are, after all, people wildly out of touch with who exactly they are.

The second point, about memory, should be clearly wrong if we take in mind our discussion of memory here. While the process by which we come to know things which we call memories is different from other knowledge, in terms of actually having those memories and recalling them, there is no difference in epistemic privilege. That is to say, the process of creating memories is special, but that of recalling them (the tangible part, from the perspective of a person) is not. The only privilege we might have is having more information about ourselves to cross-check our own knowledge with.

…Ontological

The doctrine of the individual asserts that the experience of being an individual is somehow fundamental to how we exist. That is, it is inconceivable to exist without the lifelong extension and unity of an individual. Yet we do not experience or exist in our extension over time as individuals; we exist in the present. The sort of experience which would be necessary for the doctrine of the individual is not found in our world, but in that of Slaughterhouse Five.10 The Tralfamadorians of Slaugherhouse Five are an alien species which experience their whole life at all times at the same time. For them, time truly is a line, a line which they experience fully at all times. Their life is a perpetually extended instant of experiencing their whole life, while ours is a perpetual present which changes over time. We experience a space which changes over time, while they experience space and time together in an incomprehensible instant. A Tralfamadorian experiences no change, merely a fourth dimension of what is. And this is the only way that an individual could be fundamental to ontology — for it to exist as an individual.

Most of our lives we do not experience in terms of our individuality. Sometimes, we may reflect on ourselves and our particular qualities, or categorize certain pathologies or modes of thinking as particular to us as individuals, connected deeply to our individual histories. And perhaps one could argue that this is an important aspect of our experience. I might say that it is very similar to reflection on pathologies or qualities which we may share with many others, but for now even consider that this is a very special aspect of our lives. Even then, the vast majority of our experience is not this. We are not experiencing the world as individuals, with our histories and futures literally front of mind, but instead are engrossed in the particulars of this moment. We do not experience the past, we recall it.

…Metaphysical

The doctrine of the individual asserts that the individual is a fundamental category of the world. That is, it is a part of the fundamental nature of reality. This has been the most direct target of this post, and the arguments made here have been made mostly in this direction. Attempts to find an essential, unchanging part of the person point us towards the mind. Yet attempts to justify the mind’s persistence or individual-relation through memory or continuity fall apart under close scrutiny.11 The problem with the cruder memory arguments is that they are, on their face, implausible. The problem with more sophisticated memory arguments (which are really continuity arguments) is that they place the mind within the world in their attempt to ascribe worldly concepts like simplicity and substantiality to it.

The problem with much metaphysics is that it attempts to take a God’s-eye view. Or, rather, it believes that there is a coherent God’s-eye view to take. The genius of Kant’s critical project, and the reason he effectively killed metaphysical speculation (on the subjects of God, immortality, and so on) in philosophy, was by his denial of the coherence of such attempts. His project was much more than this, encompassing a theory of our mental faculties, the possibilities of experience, and foundational texts for epistemology, ethics, and aesthetics. Yet its primary insight was critiquing the attempt to gain the wrong kind of knowledge from first principles. Rather than shedding light, attempts to talk about things like the mind which are not found in experience pull us further into confusion, not because we cannot find arguments for our positions, but because we can find altogether too many arguments for altogether too many positions. Was there a start to the universe or has it always existed? Is God a necessary being or internally incoherent? And so on. The mind is not in experience, it is that which experiences. And since we are minds, all we have is that experience to go off of. We cannot talk about the camera, only the sorts of pictures it can take, and perhaps, if we are lucky, we can get some small insight into what can make it function properly.

The notion of the individual is meant to refer to something we feel very strongly (that there is such a thing as an individual). We notice that we move through time and there are deep connections between us and our pasts as individuals. That is all well and good. We then posit some simple thing which persists identically throughout our entire life and makes us always exactly the same thing at all of those times. Yet, when we observe our pasts, on the level of experience it is clear that no such connection can be found. And if it cannot be found on the level of experience, how could it possibly have some sort of special status in experience? I mean to claim nowhere in this post that there is no such thing as an individual, or that the individual is a useless notion. What I am arguing against is the attempt to cram the self — a composite, empirical construction with no clear boundaries — into a hastily- and sharply-fenced cage.

To have certain memories, knowledge, proclivities, or stories due to one’s past experiences does say something about you. The individual is not a metaphysical necessity of human experience, but it is connected to how our experience generally functions. I have inhabited the same body for all my years alive. Certain things, in much of that time, have not changed — my fingerprints, my skin tone (to an approximation), my propensity to talk just a little louder and for just a little longer than I should. Other things have. I have a strong tie to that past-self. I feel very close to him — even the past self of many years ago. He and I have much in common, and I know a large amount of the facts about his life. Perhaps more than anyone else (except maybe his mother, because she has a much better memory than either he or I do). Bring it a few years closer to the present, and there is yet more in common, and I know even more about his life. Each experience makes an impression upon us. These experiences can compound into personality changes, new skills, different homes, and new friends. Each moment is but an impression, but we have many moments. And like the Ship of Theseus, if you go out for enough voyages, both you and your world start to look very different.

We will consider the implications of this new perspective in a future post. There is a lot of philosophy which has the problem of trying to get too much practical payoff out of first principles, and I don’t plan on repeating that mistake. That the individual is not metaphysical does not immediately imply much practically. If it does anything, it might make us more sensitive to the possibilities of different ways of thinking about ourselves, our fellows, and our worlds. The attempt to fashion an individual out of the messier reality of human beings is, when you drift down from the heady, abstract heights of philosophy, a bit silly. Ask anyone whether they’re the same person they were when they were 5 or 13 or 18 years old. They’ll likely say something along the lines of ‘a little bit of yes, a little bit of no.’ I suppose what this post is really asking is: why would we doubt that answer?

I’m going to be throwing around words like metaphysics, ontology, and epistemology throughout this post. If you don’t have experience dealing with these weird philosophisms, they can look daunting. A quick sketch: metaphysics is about the fundamental nature of reality, ontology is about the nature of existence or being, and epistemology is about the nature of truth or knowledge. Metaphysical categories are supposed to be somehow fundamental to reality, to have a sharpness and necessity that makes them special. Ontology is similar, but it is focused not on the world, but on what it is like to be, or exist. Epistemology is about what it means for knowledge or statements to be true about something, or what knowledge actually is. A full treatment of the methodological background at work here will come in a later post (planning… not my strong suit).

An argument may be made for love to be here as well — “I love you because of who your are.” Yet insofar as love is considered in this sense specifically, it is really a sort of indebtedness or ownership relation. The feeling is of a kind of loving ownership towards another person, perhaps a sort of debt accrued through intimacy and service that is taken on happily and lovingly.

Other relations may involve ownership and therefore involve identity. For instance, insofar as pride is in part a sense of ownership or responsibility over the actions of another person (or even yourself at a different time), it also at the same time relies on identity. Such a feeling of pride only makes sense if you consider that person feeling the pride to have some identity relationship across time to the action or skill or teaching exhibited in the prideworthy thing. Vengeance is similar. Whereas, say, hate is a word of qualities, vengeance takes on identity-based relationships. Vengeance requires identity, and is also a sort of debt or ownership.

No one believes a corporation is actually a coherent agent capable of having its own ownership relations, but the legal fiction that analogizes it to a person it is an incredibly effective way to allow for the marshaling of resources.

On the point of punishment, the argument is usually presented thusly: if I have no ownership relation to my past, there is no sense in which I am responsible for my past actions. If I am not responsible for my past actions, then there is no strict or necessary justification for punishing me (and only me, and always me) for them.

For more on this necessary supposition of others’ minds, you can read the first post in this series.

The memories we talk about here are memories of sensations, not memories of facts or knowledge. Memories constituted of qualia from experiences at a different point in time are those which are supposed to give the mind its numerical identity. Now, memories often decay from experiences into words, which might worry us about the firmness of this distinction. Sartre’s Nausea gives a wonderful, if sorrowful, description of this phenomenon:

For a hundred dead stories there still remain one or two living ones. I evoke these with caution, occasionally, not too often, for fear of wearing them out, I fish one out, again I see the scenery, the characters, the attitudes. I stop suddenly: there is a flaw, I have seen a word pierce through the web of sensations. I suppose that this word will soon take the place of several images I love. I must stop quickly and think of something else; I don't want to tire my memories. (P. 33)

While this fact of experience will not feature heavily in the main argument of this post, it does gesture at the haze that dominates the supposed unity of the individual.

One might argue that one is not remembering when one misremembers, but this presumes that there is something which arbitrates between the two. Who is to say when I am remembering and when I am misremembering?

This example comes from a friend, Elijah, who used it in a paper on a topic somewhat related to this one. Thanks, Elijah!

It might be of interest to note that the two tacks discussed here — memory and continuity — seem to map on, historically speaking, to the two main strands of Western philosophy in the early modern period (i.e. roughly going from Descartes’ Meditations in 1641 to Kant’s Critique of Pure Reason in 1789). Memory arguments seem to have been most popular with empiricists like Locke (unless the empiricist in question believed in no self at all, á la Hume), while simplicity and continuity were more rationalist favorites.