The Importance of Social Scripts: Masculinity, America, and Anime

What happens when young men have little idea of what is expected of them at home? Perhaps they look further out.

Taking a break from the philosophy for a moment to talk about an interesting trend. This post is a little later than I had hoped, but going to see if I can keep to an at-least-one-post-per-month schedule going forward, at least for the next year or so. Next post will hopefully be back on track.

Also, disclaimer: I feel a bit silly writing this, but just to be clear about what these words mean when I talk about groups, I feel like I should note that I believe groups to be deeply heterogeneous, and when I talk about ‘boys’ or ‘girls’, I mean shifts in averages, not clear dichotomies (as I mention again below). We are talking about differences on the margins, where social resources can really matter. Social scripts and media and culture have a limited effect, but in a country of 330 million people, limited effects can change drastic amounts of raw life.

Consider, for a moment, what it is like to be a boy early in his teenage years, whether you have been one or not. You have known for some time that girls were not boys, were something different in some way. But the strict mechanics of the situation were never quite clear. They had longer hair, sure, and on average seemed to like different things perhaps, but there was no intuitive difference to grasp onto. You had to rely on secondhand knowledge and extrapolation — you’ve been told “girls are like this, boys are like that”; you knew more girls who were like this and more boys who were like that. And, sure, as long as you had no reason to doubt such proclamations, you treated them as fact. But treating something as fact and being directly and constantly confronted with fact are two very different things. It’s different when you feel in your bones that there is something to attend to.

Over the course of a few years, some things change this chimerical difference into an unavoidable one. For a large majority of boys, you’re going to notice that you want something from girls specifically — a kiss, a hug, to hold their hand, to be close to them, to have them ‘like like’ you. You are also going to notice that your close peer competitors in sports who happened to be female are now usually weaker, slower, and/or smaller (after an awkward few years) than you. Even if they can keep up on the soccer field or racetrack, arm wrestles get much more one-sided. This combination of changes in physical reality — sexual desire and physical difference — is unimaginably jarring. Suddenly, girls qua girls matter to you deeply, and at the same time cannot physically best you in many ways. Meanwhile, you have just enough social cognizance to be anxious about people thinking about you but not enough social experience to understand how to manage that fact.

For a long time, these basic physical realities and the social institutions built up around them were omnipresent. Thanks to material changes in what matters (less physical brawn, more mental might) and incredible (and overdue) advances in female empowerment, the implications of sex difference have narrowed. Women can work and support themselves, men can work in care industries; women can be a part of public life, men can excuse themselves from military service; women can marry each other, men can do the same. This is, to my mind, good. Nonetheless, even without getting into deeply contested territories surrounding sex differences in psychology, the mere physical facts outlined above should be more than enough to provoke care for the difficult years when they come to bear and their most direct, interpersonal implications. How should we prepare (heterosexual, generally masculine) boys for this fraught part of their life? What happens when you have one group of people more physically powerful than another, and that same group of people also want very dearly something that only the second group can provide?

Social Scripts

In some — mostly left-leaning — quarters, the notion of societal norms and scripts based around things such as gender can be met with suspicion. They can be seen as oppressive, destructive, and reductive. And they can, certainly, be all of those things. However, norms and scripts also allow for coordination and can provide information to people about viable options for their lives. People — especially young, changing people — are fallible and anxious and uninformed and pulled in hundreds of different directions. It is good to have general social scripts of what anyone can do, but social scripts which focus on a particular gender can incorporate metaphors which more readily speak to people whose experiences line up with those common to that gender. Masculinity, as a concept, has a use, and can be put to the benefit of everybody (including men) if used carefully.

If boys are liable to be shocked by their changing material circumstances vis a vis their strength and sexual desire, then should we not prepare them and them specifically for that change? And with the metaphors and narratives most likely to help guide them through this change?1 Should not leftists agree that the particularities of a group’s lived experiences often leave an indelible mark on its psyche? Whether such differences can be exaggerated to the point of moral relativism is besides the point: boys need lessons which speak to them, and society needs boys which are healthy, directed, and fulfilled.

In other — more right-leaning — quarters, the notion that boys and men need new social scripts is met with suspicion. Whatever happened, some ask, to Gary Cooper? But of course, Gary Cooper and John Wayne were new social scripts upon a time. After all, standards for expression of emotion have changed repeatedly even in the last few centuries. Problems with previous conceptions, changing material circumstances, and other impetuses can all cause shifts in norms. Fewer people serve in the military, and more military roles lack emphasis on muscle power (to what extent does a logistics officer need to do more pull-ups than the enemy logistics officer?). Fewer jobs focus on muscle power, and more on machine power, intellectual aptitude, or emotional care. You can stand athwart history yelling “stop!”, but history has a way of not taking kindly to such dictats. If there is something worth preserving in masculinity, it should not so easily lose its lustre.

What is a man? Is it the moody, sensitive, gloomy Byronic hero or the snarky, unbothered, half-sincere Marvel hero? Is it more masculine to love one woman deeply or have many sexual partners? If we believe there is some accumulated wisdom in all these vicissitudes of gender norms, what does it mean for us today? The crude fact of the matter is that what a man is should be good for men and good for the world they are in. And if you look at the statistics, men are often (in America, at least) not finding a good way through the world.

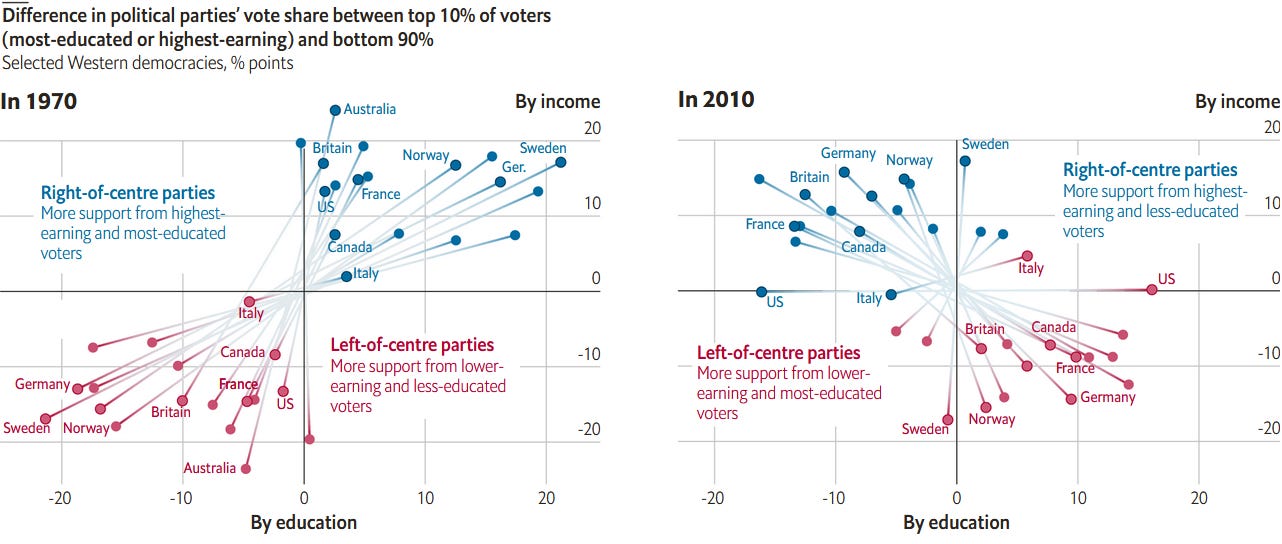

I don’t think that you can easily blame statistics on something as amorphous as male social scripts. Nonetheless, we should still be concerned with the question of whether we are serving young boys what they need in order to prepare them for one of the most important relationships of their lives: that between them and the opposite sex. The concern over the rise of the ‘manosphere’ and its influence on young men has prompted much soul-searching among liberal elites in this quarter, and is the trend most often linked to a dearth of male role models. I think that this is connected to a notion that has been mentioned by some liberal commentators such as Noah Smith that liberals in America are no longer the Revolution: rather, they are the establishment. I don’t mean liberals as in left-wingers, but the center-left. For a long time the establishment was the center-right — if you grew up with a decent amount of money, went to university, and were one of the many managers operating at the unglamourous heart of government or commerce, you were a little more often than not a conservative. Not a kook, certainly, but you leaned conservative — pride in country, policy moves slowly, suspicious of big changes. Now, the same person is almost certainly a liberal. To reduce to brute economics,2 see the following graph from this article in The Economist:

(Do not be confused: since The Economist is British, red means lefty and blue means rightist, reflecting the colors of the Labour and Tory parties in the UK)

Note that while incomes are about equal, education is highly polarized in the US. High-paying industries that require less education — business and entrepreneurship, probably — we would expect to be more conservative, while those that require more education — academia, law, medicine — we would expect to be more liberal. And the culturally influential area of media also moves leftward. We might expect, then, that liberals would become the establishment — not of everything, but of the central levers of culture. And liberals are much less comfortable than conservatives about extolling the virtues of masculinity. In liberal spaces I hear much about the strength of women and what historically feminine virtues have to offer men (see this for one example of the ‘masculinity as a problem to be solved’ literature) and little about the value of historically masculine virtues.3 There is a sense that masculinity is something to be papered over, moved past, and deconstructed and sold for parts. I don’t mean to make this sound apocalyptic, but there seems to be a sincerely held belief that it is not just toxic masculinity that is bad, but that all masculinity is and will be to some extent toxic.

Meanwhile, there is a real sense in which an ideal of masculinity is shrinking from a guide on how to live in a male body to an elaborate social game where points are scored in aggression, apathy, and athleticism. If liberals are the establishment, and liberals aren’t interested in extolling what the particular predicament of men has to teach us, then where will boys find their guides? In the manosphere? In the cruel instincts of adolescence? Well, there’s one more place I see boys looking that I have not seen many people consider, probably due to its foreign origin and recent explosion from relatively insular status: anime.

Anime and Masculinity

Caitlin Flanagan recently wrote an article which in part precipitated this piece about what she called “heroic masculinity.” The predicament at the start of the piece here is really about a fundamental temptation: you have power, so how will you wield it? Even if we ignore every bit of the ways that society still requires men’s general physical prowess, we are left with a fundamental question of gender relations: she has something you want and you can attempt to force her to give it to you. Will you? Or, she has something he wants and he is attempting to force her to give it to him. Will you let him? What, the young boy asks, does this strength mean? Are we giving him an answer?

Caitlin Flanagan argues that men, to an appreciably more regular extent4 than women, have the chance to be heroes. And hero here is specifically the protection of someone else. It is women who must most directly brave the violence, domination, and aggression of toxic masculinity. Their strength in this matter is not to be impeached. Season 1, Episode 7 of Master of None has a particularly compelling illustration of the awareness, care, and bravery that being a woman requires in a world that includes men. Two characters walk home from a bar, one male and one female. The male stumbles home drunkenly with little caution and much swagger. The female is on alert, looking over her shoulder at a man who seems like he might be following her, at one point thumbing ‘9-1’ into her phone’s keypad to make the call to the police just that bit quicker in the case that it is required. They both arrive home safe, but getting there is very different. Women must brave toxic masculinity. A man has a choice: is he going to be the reason why women feel uncomfortable walking home at night, or is he going to be trusted to walk women home at night so they can feel a bit more comfortable? As Caitlin Flanagan notes, at the crucial moment of cruelty, no law or political movement is going to save you. Your best luck is not to live in a state with a high penalty for sexual assault, but to be within earshot of a guy decent enough to understand his own responsibility.

I like the term heroic masculinity here particularly well because in these precious years when boys are coming to terms with their changing bodies and desires, they are frankly obsessed with heroes. This is not a big difference between boys and girls, to be fair — a prominent theory of education posits that around this age it is just natural to be deeply concerned with extremes, heroes, and idealism. It seems right to use heroes to help young men understand the implications of their particular situation. And here, finally, is where we come to anime, in particular the most popular genre: shounen (literally translated to ‘young man’).

Anime has long been a cultural import to America. Weebs have been around for a while now, and especially in black5 (and perhaps asian?) communities it not terribly uncommon to see male adults in their 30s even wearing shirts with graphic designs relating to anime. However, it seems to me that anime has exploded into the mainstream of young men over the last five or so years, to a much greater extent than it had before. Here I speak entirely anecdotally, but in my quiet suburban hometown everyone at least knows someone who watches anime regularly, and it’s not just the nerds anymore (nerd though I am). Almost two-thirds of Americans ‘enjoy anime’ (whatever that means) and, of import for our discussion here, around 40% of the audience at any given time is between 18 and 24 years old. Many of those people are women, but from my experience anime still runs pretty male.

It is my central contention here that one of the reasons for anime’s continued relevance and increased popularity is the dearth of compelling domestic masculine ideals and the centrality of heroes, strength, rivalry, and responsibility to shounen anime.

Shounen Tropes

It would take too long (and too much expertise) to list out all the shounen anime tropes. However, there are certain recurring themes that crop up again and again to shape the choices and lives of the characters in these shows.

Strength and Protection

Shounen anime is, quite frankly, obsessed with strength. Characters power up throughout the series, continuously talk about their shame of not being strong enough or desire to be stronger, and a question many series attempt to discuss is what it means to be powerful. For Chainsaw Man, insanity can be a kind of mental strength allowing demon hunters to continue to work in a deeply traumatic business. For most shounen anime, though, strength is about the ability to protect others. Characters curse their lack of strength when they can’t save other people, and other characters are in awe of the strength of those who can save others. What is strength for? Shounens respond enthusiastically: to be heroes, to protect people.

The importance of strength and protection to shounen anime is difficult to overstate, and it is also difficult to overstate how important these twin concepts are for any sort of positive guide for young men. There is a bit of chest-thumping pride to the notion, but it is channeled always toward service and protection. The shounen hero exclaims “I can protect you!” and stakes their pride on it. Young men get stronger. They can use that strength, abuse it, or run from it and its responsibilities.

Competition, Rivalry, and Growth

Shounen anime is replete with rivalries and obsessed with battles. Throughout all of this is the sense that “as iron sharpens iron/So a man sharpens the wit of his friend” (Proverbs 27:17). Competition and rivalry are inherent to growth, to challenging yourself and others. And shounen anime has an almost religious faith in the ability of people to grow. There is recognition of talent and gifts, but far less emphasis is put on them and much more emphasis is put on willpower, training, and competition. To quote another character from the pictured anime above (Haikyuu!!), “talent is something you make bloom. Instinct is something you polish.”

Healthy rivalry and competition is a constructive outlet and a training ground for comfort with confrontation. Furthermore, for young men, growth in strength is simply a fact of life, and having a direction for that growth is important. Stories of people growing in strength chime with many young men’s own experiences, as over the course of a few years, older physical betters become physical equals. Young men get stronger. They can deny that fact, ignore it, or take the opportunity to cultivate something important.

Service and Sacrifice

A short tangent: there is a theory of Western culture which posits that one of the things which differentiates it from many other cultures is its belief in the power of reason. European history, from the time of the ancient Greeks, had a rich fascination with mathematics, and the Enlightenment’s focus on reason’s capacity to understand the world in some part stemmed from this fascination. Mathematics was a paradigmatic example of a seemingly pure construct of reason being able to describe natural laws with an unnatural power. A faith in reason permeates Enlightenment thought, and the idea that reason can solve issues — social, technological, or moral — is still ever-present in (especially liberal) circles. This faith in reason is generally contrasted with various traditions’ (very reasonable) distrust of reason — rather than being enlightening, reason confounds and rationalizes and isolates. Reason is not the purveyor of wisdom, these traditions say, but crude self-interest and arrogance. See, for instance, the Tao Te Ching. The Dao (or ‘way’) that this short book extolls is defined by its lack of meddling, by its counterintuitiveness, and by its acceptance of the world. It should not attempt to analyze the world by reason and ‘fix’ it. “Be restless, and lose the rulership.” Rather, you should “blunt the sharpness/Untangle the knots/Soften the glare/Settle like dust/[And] let your wheel move only along old ruts.”

When we talk about culture, a lot of reductionism is necessarily involved. However, this same distrust of reason crops up in anime, too. In the video above, Akira yells “enough with the reasons!” while Shizuka wonders why someone would do something without the cold reason of self-interest.6 In many shounen anime, the hero is not particularly smart, and often foolhardy in both their ambition and appetite for risk. As one memorable line from the One Piece manga attests: “what wonders fools create!” The trope of the scheming, philosophical villain shows up commonly everywhere, but in anime there is particular attention to the ways in which we can rationalize our way out of heroism. After all, if reason is identified with self-interest, how do you reason your way to sacrifice?7 But, as many shounen anime attest, there is a sort of ambition or pride which can make sacrifice and service a joyful act. The chest-thumping that I noted earlier with regard to strength and protection comes back here, as service and sacrifice are framed as far more core to strength, correctly perceived, than domination. Strength is neutral, but strength put to the end of serving others is perhaps one of the ultimate ends of humanity.

Tropes and Masculinity

The core concepts here are strength, protection, growth, competition, and sacrifice. These are universally relevant themes, but are especially sharp in the case of young men. And that is really all that social scripts are or should be — universal lessons that are especially sharp for certain groups. It is this attitude toward strength and its implications that truly defines the contribution of shounen anime. We are inundated with lessons of being wary with power and those with power. There is certainly truth in that. Yet, we all have strength of our own, and if we only learn to distrust power, what will we do when we find it in ourselves? In young men there is a group where a certain kind of power is thrust upon them. If all they have are ‘don’t’s, they have no direction, merely closed doors. “Don’t hit girls,” “don’t be a creep,” “don’t pressure women.” These are not wrong, but should we not also teach boys what only they can do because of their strength? What they have the chance to be, should they take it?8 This sort of talk can feel a bit chauvinistic, like one is implying that women cannot handle themselves. I mean no such thing. I only mean to ask why we think we should leave it to women to handle themselves. Does it not come close to the true purpose of male strength to be able to bear at least some small part of the burden that women must carry on account of that same male strength?

I do truly believe that anime fills a domestic void in affirmative social scripts for men in America. To a young boy who sees a myriad of affirming messages for his female peers and a litany of prohibitions for his own cohort, it may sometimes feel like he is being told “girls can do anything, boys should do nothing.” Boys do not want to do nothing. They want a purpose, like most people. Let’s give them one.

So, Are We in the Clear?

One lesson to take away from this posited social phenomenon (American young men becoming deeply interested in shounen anime) is that people are generally smart, and find resources where they can get them. Word travels, society is adaptable, and cultural resources in our interconnected era have never been more abundant. No more does it take a slew of improbable coincidences for an important cultural, religious, or philosophical concept to travel far. Now, people exchange ideas across cultures so much that some get annoyed at this universal human tendency. However, as many who know about anime tangentially probably understand, there are drawbacks to outsourcing your social scripts. You might end up with ideas that you don’t quite like crowding in on ones you do. The biggest example in anime (though it perhaps is getting somewhat better?) is depictions of women. Anime is famous for absurd body proportions (in all fairness, this comes for all characters), wafer-thin female characterization, and an abundance of pervy characters. A commiseration common among anime-watchers is that every shounen has an obligatory misogynistic pervert, and you just have to hope they’re not on screen too much. This is an exaggeration, but not by too much. Exceptions abound — Jujutsu Kaisen should be singled out for particularly compelling female characters — but they abound far less than they should. While anime has much to offer, it does not seem like the optimal solution when valuable lessons for young men are mixed with a somewhat discomfiting stance towards female characters. If America wants self-determination in the values its young men are being guided by, it should produce such works itself. Anime can and should remain, but it cannot be a substitute.

The second problem is that while young men might be able to feel somewhat guided personally, or affirmed that these notions exist somewhere, they still may leave their television screens feeling lost about what, crucially, their own country wants from them. What do their neighbors expect from them? Their teachers? Their classmates? They live in America, not Japan, and what the Japanese expect from their young men will not necessarily help a young American boy know what his own situation implies.

These sorts of cultural trends are not well executed by top-down dictats. I do not expect Joe Biden, or the NYT editorial board, or Disney to come out and agree with something like this and for the problems to be solved. These sorts of things bubble up from unexpected places and random encounters, perhaps one like you happening onto this article. Really, this article wasn’t directly aiming to be a booster for anime or a diatribe against American attitudes towards masculinity. Rather, I saw two trends which I believed were connected which other people had not explored in this light. I think it is an analytically interesting example of cultural exchange, and perhaps has some implications for what positive masculine role models could look like, neither being trapped in an unworkable past (that really, I am not sure if ever worked) nor denying the problems that visions of masculinity are really trying to address and lessons that such visions more connected to classic traditions have to offer.

Such an argument would clearly apply to girls as well.

For a more qualitative and sociological depiction of this change in America specifically, there is this highly compelling thinkpiece by David Brooks: “How the Bobos Broke America.”

Nothing wrong with extolling the virtues of women, their strength, and deriving wisdom from these places! Nothing! I am all for it!

This is perhaps a good place to note again that throughout this article, and whenever large, incredibly heterogeneous groups such as ‘men’ and ‘women’ are brought up, the collapsing of their diversity into a particular trend is a statistical one. Because of the (again, statistical) fundamentals of (average) male physical power versus (average) female physical power, we expect men to be in this situation more often. these are not dichotomies, but standard distributions shifted one way or the other. This is why I speak of what the predicament of men can teach us as a whole, since it is in some ways simply a symbol for more general experiences of having power over someone.

If you find narratives about lacking male role models in black communities compelling, then this could be an interesting connection for you — the earlier prevalence of anime in black communities could be related as a secondary implication of the hypothesis I’m describing.

I know, I know, Zom 100 is technically a Seinen anime (a genre generally aimed at a slightly older male demographic than Shounen). It’s just the most clear representation of what I’m trying to get at here that I could think of off the top of my head, since this tension between Akira and Shizuka’s ways of doing things informs a lot of what the show is trying to say about the importance of passion and freedom.

Whether it should be so identified is not the topic here, but as a somewhat-avowed, somewhat-lapsed Kantian, I lean towards no.

I can’t find a good clip of it, but Jujutsu Kaisen season 1, episode 2, starting at around 18:38 has a good example of this sentiment, the idea that strength provides a particular responsibility. The pride that Yuji (the character talking in the clip) feels in his work throughout the show is then a consequence of his responsibility.