Links Through which to Think about AI [1]: Work, Cognition, and Economic Revolution

Cribbing thoughts for thinking about thought-thinking robots

This was originally going to be a single off-schedule link list post, but it kept ballooning and it felt like the subject and ideas warranted a full treatment. Now I worry that it is a bit over-full, and I have also broken it in two. Oh well. Things are often more interesting than you think. What a wonderful problem.

ChatGPT was released a little over one year ago. OpenAI is now back in the news after some corporate governance shenanigans. Some people are saying that AI is becoming just one more computer tool. It seems like a good time to talk about AI. But my ideas about AI aren’t, generally, particularly interesting. Hm. What a conundrum. My solution is to offer you the thoughts of others, which I have helpfully collated and organized as your friendly neighborhood embodied content algorithm. I’m going to shy away from the geopolitical and military applications and, for this post, focus on AI under the current paradigm of large-language models and their application in our economy.

Let’s start from the concrete.

Using AI: The Edge

The most prosaic (and, probably, the most reasonable) motivation to care about AI as it currently stands: you will be using it.

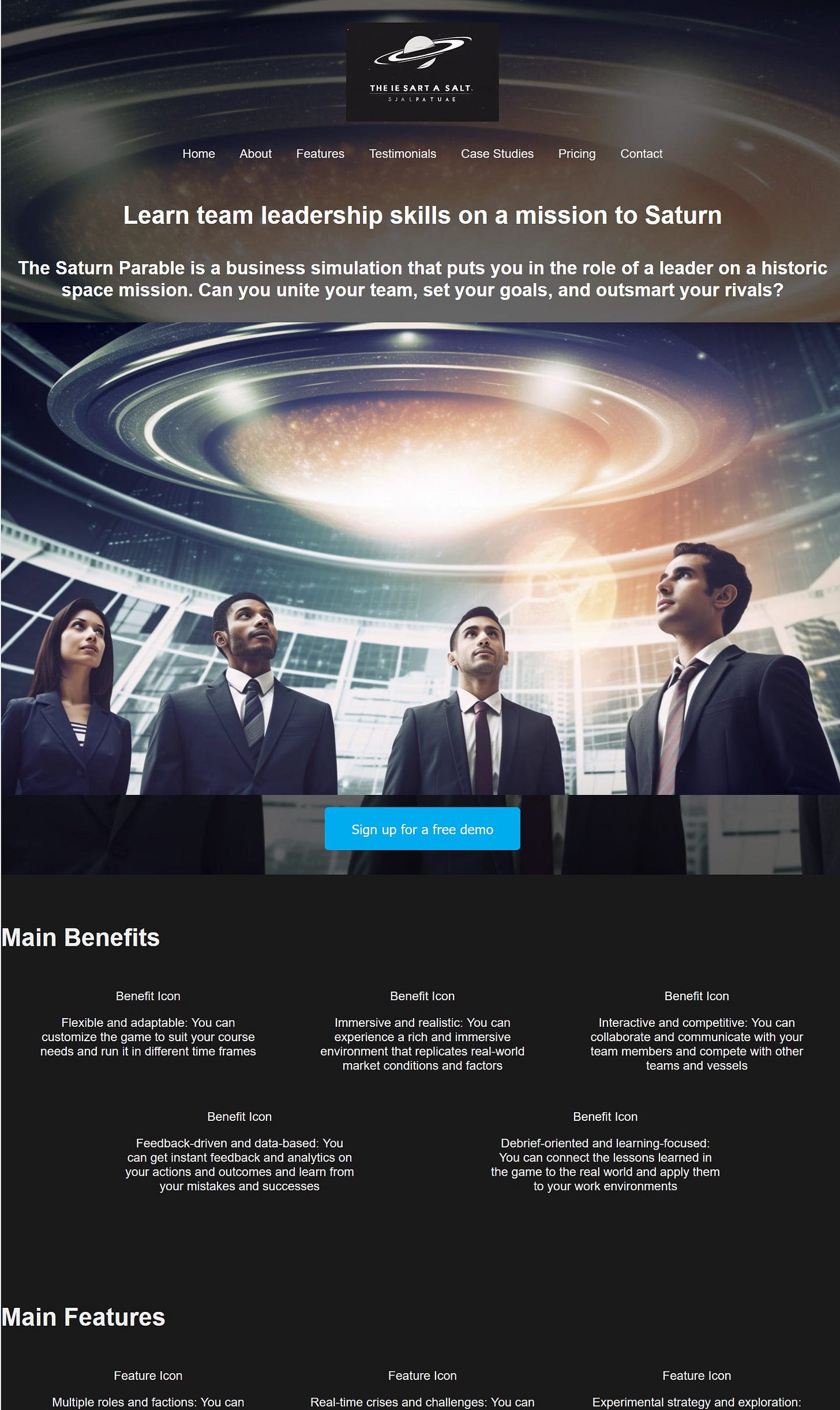

shows us why:Under the current AI paradigm — Large Language Model chatbots with the ability to write, code, and create images in response to prompts — this is what peak AI performance looks like. Someone native to the tool can create “a market positioning document, an email campaign, a website, a logo, a hero image, a script and animated video, social campaigns for 5 platforms, and some other odds-and-ends besides” in 30 minutes.

If I saw that website, I would probably think “yeah, that’s a real website” and not “what scam/horrible mistake/8th grade computer science project did I just stumble onto?” And, you know, that’s pretty much the most important bar for a website to meet.

AI is part interlocutor, part assistant, and part software engineer. Really, a helpful way to think about AI when using it is as an alien intern:

A hyper-capable, naïve, efficient, alien intern, that is. AI is very different from previous computer programs in that it is actually more helpful to think of it like a person — albeit a somewhat strange person — than it is to think of it like a string of code. It does not require exactness in inputs and it will not deliver exactness in outputs. Rather, it provides ordinary-language (or code, or image) responses to ordinary-language queries. The AI was trained on people talking, so talk to it like a person.

I have been delinquent in incorporating AI into my work, but you can see in these posts that, for white collar professionals, becoming comfortable with AI in the workplace in not an edge — it’s the whole dang blade. Learning to use AI is clearly a massive boost to your productivity.1 How massive, you ask? Well…

Using AI: Statistics

An entrepreneurial business professor can figure out how to do some neat tricks with AI, but what about every John and Jane Q. Taxpayer? What happens when everyone starts showing up to work with a strange daemon whispering sweet, algorithmically-generated nothings into their laptop? Here, we turn to a slate of experiments and surveys which compare outcomes between those induced to integrate AI systems into their work and those who were not.

In business writing tasks, workers aided by ChatGPT-3.5 could finish the same amount of work as their unaided colleagues in 60% of the time while having their work rated 18% better. Another study2 showed a variety of business analysis tasks were completed 12.2% faster and at 25% higher quality when done with AI assistance. GitHub launched an AI coding assistant and found, in September of last year, that using it halved the amount of time it took users to complete coding problems. Working with an AI assistance allowed real customer service call center employees to complete tickets 14% faster and at a higher level of quality.

But general productivity increases are not the whole story, or even the most curious part of it. Rather, the most striking quality of these productivity increases is that they make productivity more egalitarian.

Average Is Back, Baby. And it’s Better than Ever

The story of the last forty or so years in wages has been increased returns to education and skills which are correlated with education. There are two competing explanations in the economics literature for this: skill-biased technological change (SBTC) and labor market conditions/policy. There is a long back-and-forth concerning the extent to which technological change rewarding returns to education on the one hand and eroded minimum wages, deunionization, and lower top marginal tax rates on the other have contributed to an undeniable growth in wage inequality between 1979 and ~2014.

Whatever the mix of effects is, it is difficult to argue that pre-AI computer programs did not excel specifically in the sort of routine cognitive tasks which required little formal training. The routinization hypothesis points out that these jobs often required a certain amount of on-the-job learning as well as basic levels of numeracy and literacy. And they paid decently — a computer, say. (Mechanical) computers could take over those jobs, but could not do the nonroutine but low-paid service work or nonroutine but high-paid professional white collar work. Occupations were then, at the margin, polarized to low-paid and high-paid nonroutine work.

Meanwhile, the automation of computers and the interconnectedness of the internet grows the “superstar effect” of the most productive workers, as they could broadcast the fruits of their particularly productive labor to more people. The internet allows, even more than the CD or the Walkman before it, Taylor Swift to stream her music incredibly efficiently. On the margin, this means more boppin’ for us, but also means less Taylor Swift troubadours traveling to rowdy taverns and rendering rousing renditions of Red (Taylor’s Version). Or, the best accountant at the firm can zip through many more accounts on Excel than when all their judgments relied on the painstaking work of some guy thumbing through his times tables. Furthermore, all of that productivity would be, in terms of labor, his, rather than requiring both him and Jeff’s own personal ‘=SUM’ operation. Now, Jeff can do something else and the economy grows.

By automating routine work, computers increased the productivity of nonroutine professional and managerial workers. By widening the reach of the ‘winners’ of the ability game, the internet and computers increase the leverage of personal ability. This means that someone being marginally more able at a job has an increased effect on overall output — one extra unit of ‘being-a-good-singer-songwriter’ now leads to three, rather than two, units of ‘quality-adjusted-song-listening’. Hence, average is over. Graphs like the one below may be a large reason why Americans aren’t enthused about AI. Where’d our green-fields-ahead, devil-take-the-hindmost optimism go? We may have misplaced it somewhere in the last 20 or so years:

Anyway, that was then. This is now:

This graph is up there with the solar energy cost curve as one of the most important economics graphs of our current moment. The flattened slope of the treatment group reflects how the introduction of AI brought up the lowest-performing individuals far more than the highest-performing ones. Across all experiments of AI effectiveness, AI assistance increases the productivity of the least-productive workers far more than it does the most. In our current AI paradigm, AI is like a 60th percentile assistant — it’s like having someone who’s pretty good at things on call at all times. To someone who is not good at something, that is extremely valuable. To someone who is very good at something, it is much less valuable (and even, in some circumstances, may be harmful). Expect a flattening of intra-occupational incomes as ability pays less with an AI assistant. In fact, a more granular analysis might be that, well, basically everyone is below average at some part of their job, so AI can just help them at that part — AI fills in gaps. We are entering Lake Wobegon: now everyone is above average.3

How it feels to Chew 5Gum Use AI

There is a worry that automation reduces human workers to drones who simply do whatever the computer requires of them, draining all work of anything creative, challenging, or meaningful. We will discuss later the possibility of an AI-integrated future in which this is the case, but for now we are focusing on the short- and medium-term; how it actually feels to use AI as we know it. And that, to be short, is good.

From the GitHub Copilot user survey:

GitHub’s finding is supported by other experiments of AI use. AI can do what automation had done so much for manufacturing, now for the cognitive class: the boring stuff. When work is automated, workers go from doing the automated work to managing the work of the machines. It is an inconvenient truth for the Luddites among us that automation generally increases worker welfare — although, fear of automation has the inverse effect. But, well, this isn’t fear of automation per se, but fear of joblessness mediated by automation. If contemporary AI isn’t going to make our jobs miserable, what we are actually worried about is AI making our jobs nonexistent. Which brings us to…

Getting to an AI Economy

Let’s detach ourselves a bit more from the here-and-now. Technology is nothing without implementation. Sure, we’ve invented AI, but we still need to use it — use it on a wide scale and in a way that increases productivity. Otherwise, it will just go the way of the Chinese power-driven textile spinning machine. What will implementing AI look like? In short, it seems like it will look like an industrial revolution for thinking.

What Was the Industrial Revolution?

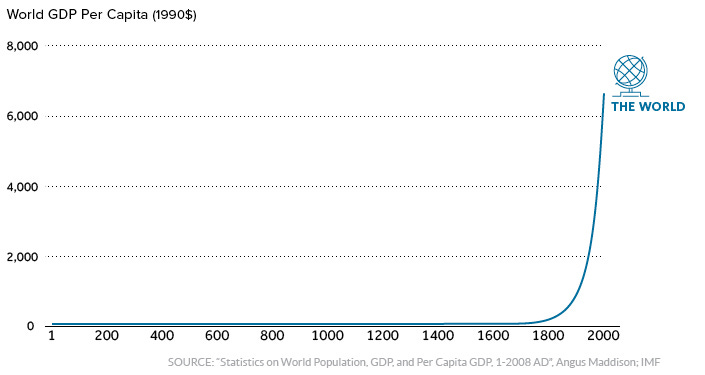

The Industrial Revolution is commonly associated with graphs like this:

What was the industrial revolution, you ask? It’s where the line starts going up. I.e. this part right here:

The industrial revolution is associated with modern economic growth, where increases in productivity greatly outstrip the pace at which population can grow and so result in increased GDP per capita.4 But here’s the trouble: it’s actually very difficult to see from the economic growth numbers that Britain’s economy was undergoing a revolution. The commercial steam engine, for its part, was invented in 1712. Modern growth rates can only be really established in the railroad age, well into the 1800s.

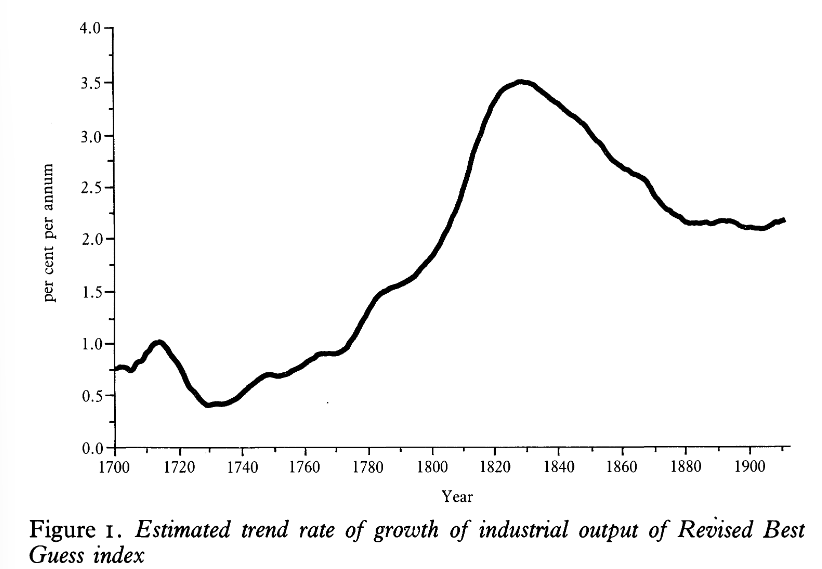

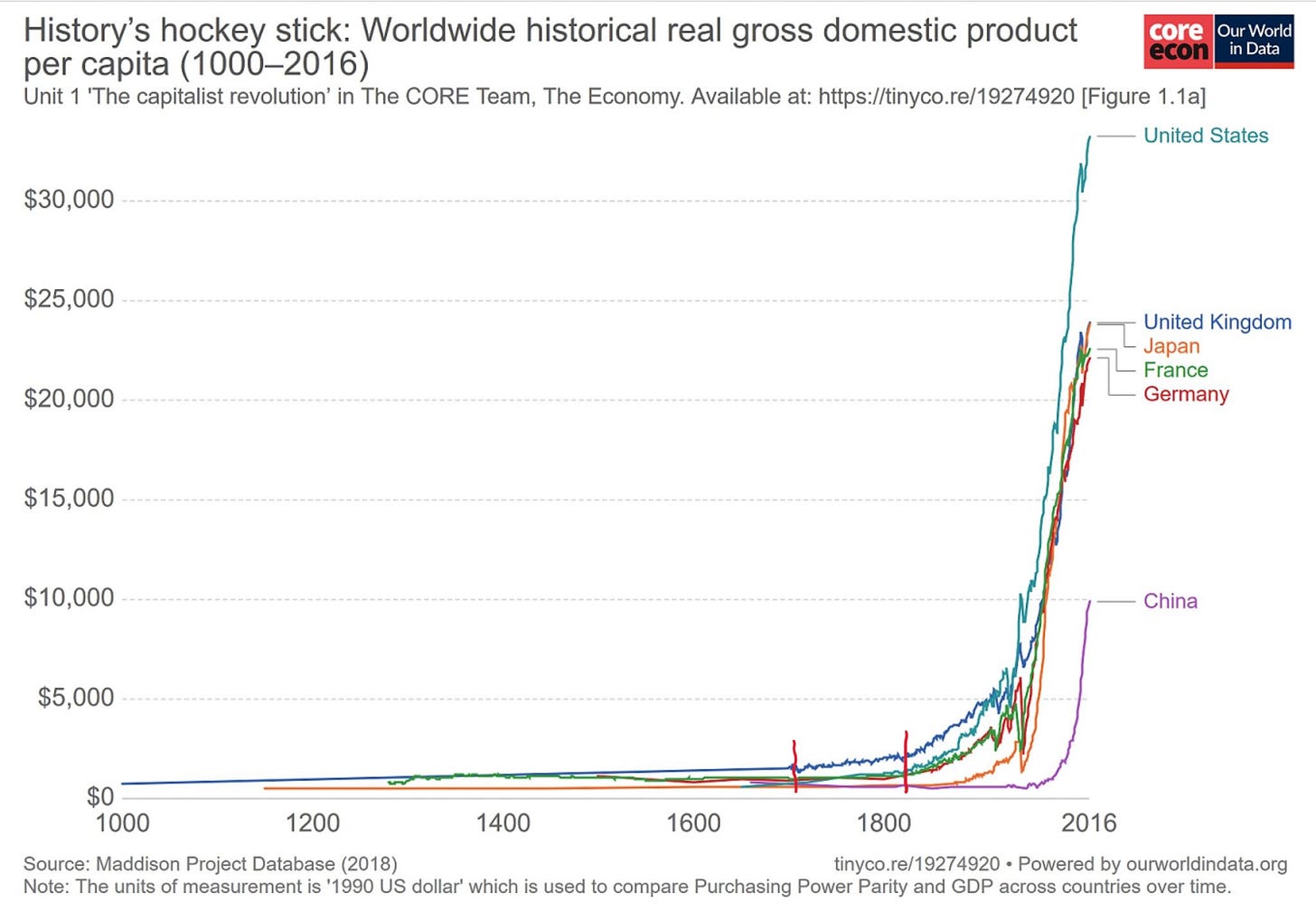

More granular expressions of world GDP graphs actually look like this:

Focus on the UK (where the industrial revolution started). It’s actually quite difficult to see anything important happening until the mid-1800s or so.

So what’s going on? Implementation. It takes a while for big changes to spread through society, and the industrial revolution was no different. Half of the genius of the industrial revolution was the steam engine; the other half was the fact that the steam engine spread. The third half was building on it.

Mineral Power

The best way to understand the industrial revolution is not as GDP starting to go up, but as a structural change in the way that the economy functioned: “The basic character of the economy changed from one dominated by the balance of land and population to one governed by technological change and capital accumulation.” Or, to put in more concrete terms:

[T]he industrial revolution was about accessing entirely new sources of energy for broad use in the economy, thus drastically increasing the amount of power available for human use. The industrial revolution thus represents not merely a change in quantity, but a change in kind from what we might call an ‘organic’ economy to a ‘mineral’ economy. …

‘Organic’ economies; … nearly all of the energy they use (with a few, largely marginal exceptions) is provided by muscle power which in turn derives from food consumption which in turn derives, ultimately, from solar energy and photosynthesis. Industrial economies, by contrast, derive the majority of the energy they use from sources other than muscle power – initially chemical reactions (burning coal and other fossil fuels) and later nuclear power, solar, etc. …

For the industrial revolution, what was needed was not merely the idea of using steam, but also a design which could actually function in a specific use case. In practice that meant both a design that was far more efficient (though still wildly inefficient) and a use case that could tolerate the inevitable inadequacies of the 1.0 version of the device. … for Newcomen [and the British] the use case did exist at that moment: pumping water out of coal mines. Of course a mine that runs below the local water-table (as most do) is going to naturally fill with water which has to be pumped out to enable further mining. Traditionally this was done with muscle power, but as mines get deeper the power needed to pump out the water increases (because you need enough power to lift all of the water in the pump system in each movement); cheaper and more effective pumping mechanisms were thus very desirable for mining. But the incentive here can’t just be any sort of mining, it has to be coal mining because of the inefficiency problem. [Emphasis in original]5

Once the flywheel of machine usage and competitive iterated improvements gets spinning, you get modern economic growth. We could substitute organic power — horses, humans, oxen — for machine power. And machine power could be iterated on and improved, and output could be far more modular. There’s a limit to how fast muscles can repair, how many muscles can work together, and how much food you can get on any acre of land for those muscles to function. There is presumably also such a limit for machines and minerals, but it is much, much further away. And that is, until about the 1950s, what most technological change was — substituting mineral power for muscle power. As mineral power was able to do more and more, different opportunities for growth were unlocked — modern pharmaceuticals are not themselves “mineral power,” but their discovery and production is only possible due to the capacities of mineral power; electricity is not itself mineral, but up to, I don’t know, around the 1950s it was exclusively based on mineral power.

The Thinking Machines

While we remain in the same post-industrial revolution era of power-substitution growth, some things have changed. The mid-20th century ended the paradigm of minerals for muscle. We are now able to decouple electricity from minerals (whether we will be able to do it entirely and in a timely manner is another question) through nuclear fission, the sun,6 wind, and the heat of the earth. And, more to our purposes here, it’s not just muscle power that we are now able to substitute for. Since the rise of computers, we have been creeping into a new economic paradigm whereby cognition is more and more able to be substituted for by computers. We not only have pushing and pulling and crushing and welding machines, but also thinking machines.

For a while, the thinking machines were relegated to very specific, repetitive, routine tasks. AI breaks this pattern and expands the cognitive possibilities of computers. Is it somewhat melodramatic to analogize this to the industrial revolution? I’m not sure. The industrial revolution was particularly important because it set the groundwork for every subsequent economic revolution. On the other hand, AI sure seems like it’s the next economic revolution. We can now substitute away from organic energy in a new large swathe of economic tasks. That’s pretty darn important!

Thinking in Timelines

Implementation is the key to economic change, not invention. So we’ve invented this version of AI. When does the economy catch up? I would say, expect peak AI to not come for at least a few decades. Our experience with electricity is indicative:

In 1881, Edison built electricity generating stations at Pearl Street in Manhattan and Holborn in London. … Yet by 1900, less than 5% of mechanical drive power in American factories was coming from electric motors. The age of steam lingered. …

Some factory owners did replace steam engines with electric motors… [b]ut given the huge investment this involved, they were often disappointed with the savings. … Why? Because to take advantage of electricity, factory owners had to think in a very different way. …

Steam-powered factories had to be arranged on the logic of the driveshaft. Electricity meant you could organise factories on the logic of a production line. … In the old factories, the steam engine set the pace. In the new factories, workers could do so.

Factories could be cleaner and safer - and more efficient, because machines needed to run only when they were being used. But you couldn't get these results simply by ripping out the steam engine and replacing it with an electric motor. You needed to change everything: the architecture and the production process. …

Trained workers could use the autonomy that electricity gave them. And as more factory owners figured out how to make the most of electric motors, new ideas about manufacturing spread. Come the 1920s, productivity in American manufacturing soared in a way never seen before or since. The economic historian Paul David gives much of the credit to the fact that manufacturers had finally figured out how to use technology that was nearly 50 years old. [Emphasis added]

Implementation for AI will likely be quicker due to the lower fixed costs of implementing it (you don’t need to build new factories, but just use new applications on your old computers), but the new skills and ways of organizing business still need to propagate through the economy before major shifts happen. We should still expect AI implementation to take multiple decades. This hypothesis might help explain why financial markets seem to have a several-decade time horizon for mass AI use. If you don’t see a massive line break in productivity, remember that reality drives straight lines on graphs, not the other way around. While humans are still in charge of the economy, it will change at a human-based speed.

But eventually, AI will be implemented, and we will have an AI economy. There are lots of different visions of what an AI economy looks like. Most of them are predicated on theories about where AI will go, not where it is. I will hold off on the notion of an infinitely powerful and perfect AI for a later date. In the meantime, we can consider something qualitatively similar to our current AI systems, but just working at a much higher quality — a 99th percentile assistant rather than a 60th percentile one. Once such an AI is implemented, what does life look like?

Visions of an AI Economy

This book is not a book about what is, but a book about what could be. The characters are modeled after persons as yet unborn, or, perhaps, at this writing, infants.

It is mostly about managers and engineers. At this point in history, 1952 A.D., our lives and freedom depend largely upon the skill and imagination and courage of our managers and engineers, and I hope that God will help them to help us

all stay alive and free.But this book is about another point in history, when there is no more war, and ... (Kurt Vonnegut, Player Piano)

So we can substitute organic power for inorganic power in a new swathe of economic activity. What does that mean? It means automating tasks. And fear of automation has been around for about as long as automation has. Kurt Vonnegut’s book Player Piano, quoted above, is something of a bible for a certain sort of neo-Luddite handwringing. Its central concern is “a problem whose queasy horrors will eventually be made world-wide by the sophistication of machines. The problem is this: How to love people who have no use.” The book depicts a small cognoscenti still gainfully employed while the rest of the population wiles away its time on booze, trivialities, and barbarity. This boils over into a massive act of sabotage whereby a huge amount of economic capacity is destroyed in the hopes of making room for workers. It is implied that, for a while, everyone — workers and managers alike — will rebuild together, until the whole thing starts again. The vision seems somewhat informed by the postwar economic miracle of Western Europe, but is a striking vision nonetheless.

Here is the worry, in economic terms: short-term firm-level effects on employment can diverge sharply from long-term market-level effects. Say I have a groundbreaking new farming technique which doubles the productivity of my farm. This allows me to hire many new workers as I work to increase my profits — the cost per unit of wheat has gone down, but I can sell them at a lower price and beat out my competitors, so I should sell more wheat until it becomes uneconomical again. On the micro scale, more agricultural workers! However, once the technology spreads (or other firms dissolve), all farms have this lower cost curve. So, the extra profit is competed away, and the labor force of the market overall (presuming the quantity of wheat demanded at the new price is not absurdly higher) shrinks. Where do the rest of these workers go? Are they thrown out on the street like bums?

Similarly, while the initial implementation of AI might mean that suddenly-uber-profitable firms hire oodles of white collar employees, those profits will be competed away. If demand for such services will not explode in tandem with supply, we might worry about white collar professionals being laid off en masse. And then what would we do!

Will the Free Market Provide?

A common view made somewhat unfashionable by the horribly scarring one-two punch of the sharp ‘China shock’ to US manufacturing employment and the unnecessarily long, painful recovery to the Great Recession is that, well, for the most part, the free market provides. One worry is that a massive technological shock could upend the labor market, kicking people out of jobs before there is a chance for generational change, reskilling, and occupation creation to smooth the experience.

Empirical considerations for this view:

Anyway, we now have a pretty concrete example of a job being automated by AI. A new working paper by Hui, Reshef, and Zhou finds that when ChatGPT was released, demand for freelancers on an online freelancing platform immediately went down. Here’s a graph by the ever-excellent John Burn-Murdoch:

Source: John Burn-Murdoch

This result is pretty clean; the methodology is simple and obvious, and the causality is clear. That said, there are a couple of questions we need to answer before we really know the impact of ChatGPT on the jobs of freelancers:

Did the freelancers get other jobs elsewhere, or become unemployed?

If they got jobs elsewhere, were those jobs in similar fields (e.g. checking the output of AIs for hallucinations, etc.)?

If they got jobs elsewhere, did those jobs pay more or less than their previous freelancing gigs paid?

In general, any new technology will shift the demand for the types of jobs people do, destroying demand in some occupations and boosting it in others. The balance of these is very hard to measure, especially over the long run.

It’s possible that many of the freelancers who lost gigs from the emergence of ChatGPT will gain better jobs elsewhere — for example, I was a freelance editor in Japan before I went to grad school, but I make more money as a result off getting out of the freelance world and getting my PhD. Maybe if freelancing hadn’t been so lucrative at the time I would have gone to grad school a year earlier. (Whether that would have made me happier is another question entirely.)

We are still in the thick of it and trends can be very difficult to see from such a vantage point. Some historical analysis is helpful here:

Tyna Eloundou of OpenAI and colleagues have estimated that “around 80% of the us workforce could have at least 10% of their work tasks affected by the introduction of llms”. Edward Felten of Princeton University and colleagues conducted a similar exercise. Legal services, accountancy and travel agencies came out at or near the top of professions most likely to face disruption.

Economists have issued gloomy predictions before. In the 2000s many feared the impact of outsourcing on rich-world workers. In 2013 two at Oxford University issued a widely cited paper that suggested automation could wipe out 47% of American jobs over the subsequent decade or so. Others made the case that, even without widespread unemployment, there would be “hollowing out”, where rewarding, well-paid jobs disappeared and mindless, poorly paid roles took their place.

What actually happened took people by surprise. In the past decade the average rich-world unemployment rate has roughly halved (see chart 2). The share of working-age people in employment is at an all-time high. Countries with the highest rates of automation and robotics, such as Japan, Singapore and South Korea, have the least unemployment. …

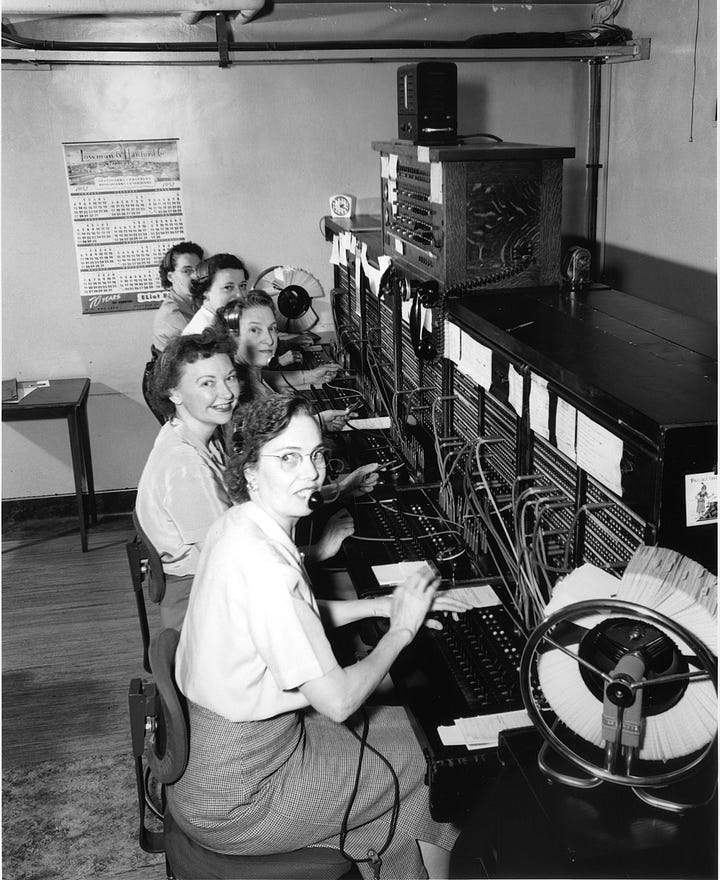

[H]istory suggests job destruction happens … slowly. The automated telephone switching system—a replacement for human operators—was invented in 1892. It took until 1921 for the Bell System to install their first fully automated office. Even after this milestone, the number of American telephone operators continued to grow, peaking in the mid-20th century at around 350,000. The occupation did not (mostly) disappear until the 1980s, nine decades after automation was invented.

In bits of the economy with heavy state involvement, such as education and health care, technological change tends to be pitifully slow. The absence of competitive pressure blunts incentives to improve. Governments may also have public-policy goals, such as maximising employment levels, which are inconsistent with improved efficiency. These industries are also more likely to be unionised—and unions are good at preventing job losses. …

Perhaps, in time, governments will allow some jobs to be replaced. But the delay will make space for the economy to do what it always does: create new types of jobs as others are eliminated. By lowering costs of production, new tech can create more demand for goods and services, boosting jobs that are hard to automate. A paper published in 2020 by David Autor of mit and colleagues offered a striking conclusion. About 60% of the jobs in America did not exist in 1940. The job of “fingernail technician” was added to the census in 2000. “Solar photovoltaic electrician” was added just five years ago. The AI economy is likely to create new occupations which today cannot even be imagined. [Emphasis added]

So we should expect the transition to be gradual. AI is not a recession or a trade agreement. It is a technology that will have to propagate the economy like any other. And, of course, things right now really are looking up for workers — they are looking so up that it seems like the last three or so years may have wiped out as much as 38% of the increase in wage inequality between the years 1980-2014. So holding course with an eye to innovation and growth seems reasonable. Right now, I would bet on dynamism.

Even if we should not be unduly worried about the transition, we still have the question of what exactly we are transitioning to.

Consumption: Shrinking Baumol

Here’s something that could happen. Say there are two goods: widgets and doohickeys. They both cost $5 and people generally need similar amounts of them, though they do different things. Now, one day, a bright-eyed young man named Philo Farnsworth comes blasting out of Utah with a great sense of style and an idea that will revolutionize widgets forever. He rolls up with his blueprints and a copy of the bible of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints and says “fellas, we’re gonna make widgets on the cheap.” And so you do! You double the production of widgets while halving the cost and after some economic magic widgets are flying off the shelves at just $1 a piece!

What a brilliant day for your community. But what’s this? People have got a little extra cash in the bank. Sure, they might want to hold onto some of it, put it in the bank for a rainy day, but… I mean those doohickeys are looking pretty darn neat. Since it costs less to buy a widget, people have more budget for buying doohickeys! But doohickeys haven’t seen the same productivity increase as widgets…

As we increase the production of doohickies, we would expect some things to start happening. Workers less well-suited for doohickey-production would move into doohickey-making, materials and land less well-suited for doohickey-production would also be required and used, and prices would increase for doohickies. Certainly, we would be richer, but doohickies would cost more. We might hear people complaining about doohickey prices or souring on the whole notion of doohickey consumption. People might become very concerned with trends such as too many administrators in doohickey firms, unfocused government subsidies giving doohickey firms a free pass, or political views out of touch with the rest of the community becoming dominant at doohickey firms. Some of these concerns might even be true! But without a productivity boost for doohickey production, they would just be mitigating what is at base an economic reality: we can buy more doohickies, and they cost more now. Also, we might even expect doohickey workers to earn higher wages relative to widgets than they did in the pre-Philo era.

No, the graph is not telling you that life was better in the 1950s. What it’s telling you is that “growth may be constrained not by what we are good at but rather by what is essential and yet hard to improve.”

Baumol’s cost disease is an economic theory which posits that as productivity increases in certain sectors and remains stagnant in others, costs and wages in the stagnant sectors will increase more than those in the increasingly productive areas of the economy. We discussed earlier that what separates computers and artificial intelligence from previous industrial tools is that they substitute mineral energy for organic energy in the non-physical realm. For a very long time, productivity increases came for textiles and manufacturing (one reason why manufacturing and textiles are particularly important industries for developing countries). Computers brought productivity increases into computational work and helped polarize the economy. AI is bringing productivity increases into complex cognitive work. The internet brought productivity increases into… cat videos? I don’t know maybe work from home? Or not? Telehealth? If we let it? It was quite probably necessary for AI development, I suppose. I don’t know.

The important part being that the things AI is good at are things we value, and opening up new areas of consumption (such as, perhaps, education) to productivity increases is especially important. The important thing to remember about Baumol’s cost disease is that it is a byproduct of getting richer, not poorer. But it is still a disease, and AI may be something of a palliative, if not a partial cure.

As a consumer of products, AI will be an unmitigated good. It will increase supply and things will be cheaper for you. No one is worried about that. But the difficult thing about people is that they are not merely consumers. They are also producers.

Production: Against Ilium

Kurt Vonnegut’s Player Piano took place in Ilium, an invented city in New York cleft in three: “In the northwest are the managers and engineers and civil servants and a few professional people; in the northeast are the machines; and in the south, across the Iroquois River, is the area known locally as Homestead, where almost all of the people live. If the bridge across the Iroquois were dynamited, few daily routines would be disturbed. Not many people on either side have reasons other than curiosity for crossing.” Almost all the people are without a use. They spend their days in bars, standing around potholes, and possibly cheating on their spouses. Husbands stare stupidly at screens or beer bottles, wives pretend to make homes (while the machines actually do), and all the dignity inherent to work lingers around the Homestead as a sick, taunting ghost of economies past. There are two questions here: first, is this an economy that will likely happen due to mature AI? And second, is this what people are like without economically necessary work? Let us consider these in turn.

(1) Ha-ha, You Fool! You Fell Victim to One of the Classic Blunders, the Most Famous of Which Is “Never Get Involved in a Land War in Asia,” but only Slightly Less Well Known Is this: Never Forget about Comparative Advantage When the Economy Is on the Line!

You should also not go in against a Sicilian when death is on the line, but that is neither here nor there.

In a joint blog post that is especially worth reading in its entirety,

and give the following:No one knows, of course, but we suspect that AI is far more likely to complement and empower human workers than to impoverish them or displace them onto the welfare rolls. This doesn’t mean we’re starry-eyed Panglossians; we realize that this optimistic perspective is a tough sell, and even if our vision comes true, there will certainly be some people who lose out. But what we’ve seen so far about how generative AI works suggests that it’ll largely behave like the productivity-enhancing, labor-saving tools of past waves of innovation.

AI doesn’t take over jobs, it takes over tasks

If AI causes mass unemployment among the general populace, it will be the first time in history that any technology has ever done that. Industrial machinery, computer-controlled machine tools, software applications, and industrial robots all caused panics about human obsolescence, and nothing of the kind ever came to pass; pretty much everyone who wants a job still has a job. As Noah has written, a wave of recent evidence shows that adoption of industrial robots and automation technology in general is associated with an increase in employment at the company and industry level.

That’s not to say it couldn’t happen, of course – sometimes technology does totally new and unprecedented things, as when the Industrial Revolution suddenly allowed humans to escape Malthusian poverty for the first time. But it’s important to realize exactly why the innovations of the past didn’t result in the kind of mass obsolescence that people feared at the time.

The reason was that instead of replacing people entirely, those technologies simply replaced some of the tasks they did. If, like Noah’s ancestors, you were a metalworker in the 1700s, a large part of your job consisted of using hand tools to manually bash metal into specific shapes. Two centuries later, after the advent of machine tools, metalworkers spent much of their time directing machines to do the bashing. It’s a different kind of work, but you can bash a lot more metal with a machine.

Economists have long realized that it’s important to look at labor markets not at the level of jobs, but at the level of tasks within a job. In their excellent 2018 book Prediction Machines, Ajay Agrawal, Joshua Gans, and Avi Goldfarb talk about the prospects for predictive AI – the kind of AI that autocompletes your Google searches. They offer the possibility that this tech will simply let white-collar workers do their jobs more efficiently, similar to what machine tools did for blue-collar workers.

Daron Acemoglu and Pascual Restrepo have a mathematical model of this (here’s a more technical version), in which they break jobs down into specific tasks. They find that new production technologies like AI or robots can have several different effects. They can make workers more productive at their existing tasks. They can shift human labor toward different tasks. And they can create new tasks for people to do. Whether workers get harmed or helped depends on which of these effects dominates.

In other words, as Noah likes to say, “Dystopia is when robots take half your jobs. Utopia is when robots take half your job.”

Comparative advantage: Why humans will still have jobs

You don’t need a fancy mathematical model, however, to understand the basic principle of comparative advantage. Imagine a venture capitalist (let’s call him “Marc”) who is an almost inhumanly fast typist. He’ll still hire a secretary to draft letters for him, though, because even if that secretary is a slower typist than him, Marc can generate more value using his time to do something other than drafting letters. So he ends up paying someone else to do something that he’s actually better at.

Now think about this in the context of AI. Some people think that the reason previous waves of innovation didn’t make humans obsolete was that there were some things humans still did better than machines – e.g. writing. The fear is that AI is different, because the holy grail of AI research is something called “general intelligence” – a machine mind that performs all tasks as well as, or better than, the best humans. But as we saw with the example of Marc and the secretary, just because you can do everything better doesn’t mean you end up doing everything! Applying the idea of comparative advantage at the level of tasks instead of jobs, we can see that there will always be something for humans to do, even if AI would do those things better. Just as Marc has a limited number of hours in the day, AI resources are limited too – as roon likes to say, every time you use any of the most advanced AI applications, you’re “lighting a pile of GPUs on fire”. Those resource constraints explain why humans who want jobs will find jobs; AI businesses will just keep expanding and gobbling up more physical resources until human workers themselves, and the work they do to complement AI, become the scarce resource.

The principle of comparative advantage says that whether the jobs of the future pay better or worse than the jobs of today depends to some degree on whether AI’s skill set is very similar to humans, or complementary and different. If AI simply does things differently than humans do, then the complementarity will make humans more valuable and will raise wages.

And although we can’t speak to the AI of the future, we believe that the current wave of generative AI does things very differently from humans. AI art tends to differ from human-made art in subtle ways – its minor details are often off in a compounding uncanny valley fashion that the net result can end up looking horrifying. Anyone who’s ridden in a Tesla knows that an AI backs into a parallel parking space differently than a human would. And for all the hype regarding large language models passing various forms of the Turing Test, it’s clear that their skillset is not exactly the same as a human’s. [Emphasis added]

Really, again, the whole post is incredible and I would just copy-paste it here if I wasn’t worried about this already-overblown post.

AI has a ‘jagged frontier’ of ability, where its comparative skills do not line up to an intuitive human understanding of difficulty. As long as that frontier is jagged, there will be a comparative advantage for people, there will still be jobs for people. The only way that such comparative advantage wouldn’t matter is if demand for all goods stalled absolutely within the productive sphere of AI and the cost of using AI to produce everything that everyone could possibly want is lower than using all the humans we have just kind of lying around consuming things. This seems, well, unlikely. Especially, again, with the caveat that we are thinking about all of this from under our current paradigm of AI, where every time you enter a query, you’re essentially “lighting a pile of GPUs on fire.” The most famous social movement based around fears of automation was the Luddites, who might be interested to know that even 200 years on, there are still jobs for people.

However, this is not conceptually impossible, so let’s talk about it.

(2) Who Even Plays Piano Anymore?

The title Player Piano is obviously meant to evoke the automation of a beautiful human act — an inversion and obsoletion of a piano player. As work becomes automated, the idea goes, we lose something beautiful and meaningful.

There’s one problem with this title. Player Piano sales peaked in the mid-1920s before people substituted away from them into phonographs, records, and eventually modern speakers and headphones with now constant access to automated music-playing through streaming. Do you think young people know how to play instruments at higher or lower rates than old people? Higher.7

The problem with the title “Player Piano” is that people still play pianos. In fact, more of them play pianos now than before! Automating music hasn’t led to a dearth of people playing music for one another, but (combined with generally increased wealth) instead has led to a massive industry of us teaching each other music so we can give it to one another as a gift.

Now, a counterpoint: the dignity of work is something special. The feeling of being needed, of having an affirmative, specific obligation is something that automation can take away and cannot be given back by leisure. Without it, we would be useless, perhaps quietly despairing of loneliness or swaddled in our technological coccoons. And Player Piano, if nothing else, is an absolutely magnificent expression of the necessity of work and obligation to the formation of a person. What would be do without it?

Let’s consider this in three ways:

If a machine can do it, will we still strive for it/think it is worthy?

If a machine can think, what could we possibly be worth to one another?

If a machine can provide, will we still grow as people?

I will answer the first question with another question: a computer bested the world’s best chessplayer in 1997. Since then, do you think that interest in the game has grown or lessened? By this point, you must know what I am going to say: grown. Relatedly, making a robot that could beat you at any video game is almost trivial. I have not brought this specific point up with anyone I play video games with, but I doubt it would get them to stop. I don’t believe that telling a strongman that a forklift could beat him in lifting a big rock would get him to quit the game. People love games and competition and will continue to compete and strive at what they love for as long as there are people to compete against and strive with. What we might see is more mingling of work and play as what we call work becomes less a material necessity and more a passionate obligation, acted out as an expression of care rather than an actually necessitated sacrifice.

The second question is a product, it seems to me, of the sorts of people who write for publications and worry about things like AI publicly. These are people who are good at writing and thinking and get paid to write and think and (probably) grew up being good at writing and thinking and got praised for being good at writing and thinking and get a lot of pleasure and pride out of writing and thinking and are now writing and thinking about a technology which writes and thinks. To be sympathetic to our new John Henries, it really is true for them that writing and thinking are very important to self-conception. But it seems a bit provincial to proclaim that what makes the human life worth something is thinking well, or that we won’t be able to adapt to life where machines can think as good or better than us. Does it really seem fair to the median schoolkid to say that thinking is what gives human life dignity or worth? Does that even seem right? One mustn’t be fooled by the fact that humans are the most intelligent animal into thinking that being the most human means being the most intelligent.

The third question is the real kicker. And, to be honest, I don’t know. At least, I don’t have a snappy answer to it. But if AI means that no one goes hungry, I’d run that risk a million times over.

AI Is a Revolution; We’ve Had Revolutions Before

My general takeaway from all of these disparate pieces is that AI, under its current paradigm, represents an economic revolution, but an economic revolution not entirely unlike the ones we’ve had before. It will change the fundamental mechanisms at play in a different area of the economy, but it will do so in a way not dissimilar to how other areas of the economy have changed. No longer is it merely manufacturing workers dealing with robots and machines while nice young men8 line up outside a law school thinking “yep, this is what legal work will roughly look like for the next 70 years”; rather, those nice young men will have the same sort of companion working beside them, except instead of driving steel, it’s doing pro forma contract writing.

At some point in the future, I am planning on writing a post on ways of thinking about what exactly AI is, what possible futures of AI omnipotence or near-omnipotence could look like, and philosophical implications of those possibilities. This post was more inspired by the line of thinking that, well, AI right now is going to be one more part of our economy. What’s the deal with that? Moving into the high-flung reaches of X-risk and computer science will require us to exit econ blogger-land and enter Effective Altruism-land (EA-land). My passport was issued by econ blogger-land, but I have long found the Effective Altruism community curious. However, these sorts of concerns are also more directly what the OpenAI kerfuffle was about, and so perhaps a bit more relevant.

Ever since we started thinking about computers, we’ve thought “what if computers were more like us? What if they could really think?” And, well, ¯\_(ツ)_/¯

Productivity: output per hour worked.

The post linked here is a bit more complex than this conclusion. There are other possibilities, such as high performers needing more time to bring AI contributions up to their level, future AI helping high performers just as much as low performers, or the discovery of ‘AI kings’ who are particularly brilliant at co-working with AI. Nonetheless, initial findings push towards contemporary AI as a levelling tool.

One of the most exquisite ironies in all of the history of economic thought is that Malthusian economics (where wealth is a function of population over productive land) describe fairly well actual economic reality for a fantastically large period of history — it’s just that Malthus actually published his theory in 1798, around the time when it began to lose all semblance of explanatory power. Talk about fighting the last war.

This is just one example of the many historical coincidences that produced the industrial revolution, but it is indicative. There is more about the specific historical context which lined up in Britain to produce such a moment in the link.

The fact that after all this time we may come back to photosynthesis being our main source of energy shows that the economy is not entirely without its own sort of poetry.

To the point of whether these suggestive examples have predictive power, this was not something I knew before searching for it. Also, on confounders, note that younger Americans who play instruments do not seem like they have more pushy parents. In fact, more of those 30 and under (by percentage) say that their parents discouraged them from music than those 45 and older (30- to 44-year-olds are outliers). So the story is not parents wanting their kids to have more extracurriculars. The effect also extends to the UK.

Very, very nice young men who should definitely remain employed and should not really be rethinking going to law school based on this innovation. Ahem.

One thing I believe I missed discussing here was that economic dislocations and job losses can be locally harmful even if they are at the same time the lifeblood of economic growth. The policy prescription for this, of course, is not overregulation and stagnation, but is and always will be a strong welfare state to insure us against our own progress.

Related: https://slatestarcodex.com/2014/08/16/burdens/ https://www.slowboring.com/p/lots-of-people-lose-jobs-even-in